Chapter 1: From Confederation to Constitution: Political Developments 1776-1788

In 1776, Pennsylvania adopted the most democratic state constitution in the new United States. A one-house legislature, elected by all male taxpayers, would rule, and the governor would have little real power. When he heard about Pennsylvania's radical constitution, John Adams exclaimed, "Good God! The people of Pennsylvania in seven years will be glad to petition the Crown of Britain for reconciliation in order to be delivered from the tyranny of their new Constitution."

As the American Revolution dragged on, the new Pennsylvania constitution became increasingly unpopular Benjamin Rush and the emerging opponents found it "big with tyranny." So intense was the political strife that the two parties formed - the Constitutionalists, who supported the radical government, and the Republicans, who opposed it - and ran slates of candidates, campaigned vigorously, and voted en bloc in the state legislature.

Benjamin Rush and the emerging opponents found it "big with tyranny." So intense was the political strife that the two parties formed - the Constitutionalists, who supported the radical government, and the Republicans, who opposed it - and ran slates of candidates, campaigned vigorously, and voted en bloc in the state legislature.

At first, Joseph Reed, George Bryan, David Rittenhouse,

David Rittenhouse, William Findley,

William Findley,  Robert Whitehill, and other Constitutionalist leaders jealously guarded their newly-won authority, with mixed results. They assumed control of the public lands owned by the Penn family and passed an act for the gradual abolition of slavery. At the same time, however, they also imposed a strict wartime loyalty oath. Those who refused to swear it - including

Robert Whitehill, and other Constitutionalist leaders jealously guarded their newly-won authority, with mixed results. They assumed control of the public lands owned by the Penn family and passed an act for the gradual abolition of slavery. At the same time, however, they also imposed a strict wartime loyalty oath. Those who refused to swear it - including  Quakers, Moravians, and other Pennsylvanians whose religious beliefs forbade them from taking oaths - could not vote, serve on juries, sue in court, buy or sell real estate, or bear arms. When the war ended, the Constitutionalists could no longer thrive on their emotional appeals to the patriot cause, and their poor administration of the government resulted in their removal from power.

Quakers, Moravians, and other Pennsylvanians whose religious beliefs forbade them from taking oaths - could not vote, serve on juries, sue in court, buy or sell real estate, or bear arms. When the war ended, the Constitutionalists could no longer thrive on their emotional appeals to the patriot cause, and their poor administration of the government resulted in their removal from power.

Examples of the divisions within the state abounded. In 1779, Charles Willson Peale and

Charles Willson Peale and  Timothy Matlack had to defend

Timothy Matlack had to defend  James Wilson against their own followers, who attacked his Philadelphia house because like many members of the elite, he retained a sympathy and friendship for loyalists. Neither Congress nor the national government could pay the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line: the first to answer Congress' call to join General Washington outside Boston in 1775 and form the Continental Army, they were also the first to mutiny on a large scale in 1781 and again in 1783.

James Wilson against their own followers, who attacked his Philadelphia house because like many members of the elite, he retained a sympathy and friendship for loyalists. Neither Congress nor the national government could pay the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line: the first to answer Congress' call to join General Washington outside Boston in 1775 and form the Continental Army, they were also the first to mutiny on a large scale in 1781 and again in 1783.

Pennsylvanians refusal to pay taxes and the inability of the government to collect them accompanied the federal government's failure to raise money. In 1781, state president Joseph Reed had to pardon the troops and promise them payment, which they received later in the decade in the form of western lands. In 1783, rambunctious troops chased Congress out of Philadelphia. Nor could either the federal or state government protect settlers in western Pennsylvania. In 1782, Indians burned Hanna's Town, the intended capital of Westmoreland County.

After 1786, the Republicans assumed control of Pennsylvania government, and changed their name to Federalists. Led by Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, James Wilson,

Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, James Wilson, George Clymer and

George Clymer and  Robert Morris, they quickly repealed the Constitutionalists' loyalty oath, restored suffrage to property-owning citizens who had been disenfranchised, and championed the movement to strengthen the national government by revising the

Robert Morris, they quickly repealed the Constitutionalists' loyalty oath, restored suffrage to property-owning citizens who had been disenfranchised, and championed the movement to strengthen the national government by revising the  Articles of Confederation, which governed the new nation.

Articles of Confederation, which governed the new nation.

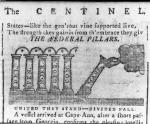

On May 25, 1787, fifty-five delegates from twelve states (the exception being Rhode Island) convened at the Pennsylvania State House, called to amend the Articles, but it was an open secret that they, and the Congress and state legislatures that authorized the meeting, intended to create a new frame of government. The new constitution they drafted was based on the principle of "federalism," or the division of powers between the state and national levels. The new federal government would consist of three branches: a legislature, which made the law; an executive, which enforced the law; and a judiciary, which interpreted the law. To prevent an excessive accumulation of power within any single branch, the framers created a system of checks and balances among the three branches.

Pennsylvania and its eight delegates - the most of any state - played an important role in framing and adopting the Constitution. Living in a state where the failure to balance diverse ethnic, religious, class, and geographic interests had led to frontier warfare and the nation's most convulsive internal revolution, they led the way in achieving compromise among delegates who disagreed on the shape of the new government. James Wilson argued successfully that immigrants be granted equal citizenship: he and two other Pennsylvania delegates, Robert Morris and Thomas Fitzsimmons, were immigrants themselves.

Sympathetic to the needs of both large and small states, John Dickinson, who had served as president of both Pennsylvania and Delaware, helped arrange the compromise that granted equal representation to the states in the Senate, and representation by population in the House of Representatives. Benjamin Franklin, on several occasions, persuaded the overheated delegates - not only did tempers flare, but they were literally sweltering in a brick building with the windows closed to preserve secrecy - to calm down. His

John Dickinson, who had served as president of both Pennsylvania and Delaware, helped arrange the compromise that granted equal representation to the states in the Senate, and representation by population in the House of Representatives. Benjamin Franklin, on several occasions, persuaded the overheated delegates - not only did tempers flare, but they were literally sweltering in a brick building with the windows closed to preserve secrecy - to calm down. His  final speech circulated throughout the nation, made a strong case for compromise in the interest of unity.

final speech circulated throughout the nation, made a strong case for compromise in the interest of unity.

Dickinson's success appears in the fact that Delaware and Pennsylvania were the first two states to approve the constitution. Pennsylvania's approval, however, was problematic. The state legislatures could not vote on the Constitution; they had to call ratifying conventions open to all adult males, thus simulating the agreement required by philosopher John Locke for people to leave a state of nature and form a government. But the Pennsylvania state legislature required a two-thirds majority to meet, legally, and the Federalists (former Republicans) lacked the two representatives they needed to muster such a majority.

The anti-Federalists (former Constitutionalists) decided to simply not show up. So a Federalist crowd sought out two of these assemblymen, physically carried them into the legislative chamber, and kept them there until the vote passed. Pennsylvania's convention then voted 2-1 to approve the Constitution, but anti-federalists Robert Whitehill and William Findley first voiced what would become the main objection to the document: it lacked security for popular rights. Their points, echoed throughout the state conventions, ultimately were distilled into the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

Their points, echoed throughout the state conventions, ultimately were distilled into the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

While the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were working on a new frame of national government, people excluded from political life in Pennsylvania organized to obtain equal rights and call the nation's leading statesmen's attention to their plight. In 1787, Philadelphia's Jewish congregation, Mikveh Israel, petitioned the Constitutional Convention asking that the Constitution not bar people from political participation for their religious beliefs: Jews could not take the Christian oath required by the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. They were pleased to learn the Convention never even considered such a restriction.

Mikveh Israel, petitioned the Constitutional Convention asking that the Constitution not bar people from political participation for their religious beliefs: Jews could not take the Christian oath required by the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. They were pleased to learn the Convention never even considered such a restriction.  The Free African Society and

The Free African Society and  Pennsylvania Abolition Society, both founded in 1787, unsuccessfully fought for an immediate end to the slave trade. African Americans did, however, receive the legal right to vote in Pennsylvania, unlike women, a group of whom would demand full political rights in 1794, and insist on being called "Citess," following the example of their French sisters during that nation's revolution.

Pennsylvania Abolition Society, both founded in 1787, unsuccessfully fought for an immediate end to the slave trade. African Americans did, however, receive the legal right to vote in Pennsylvania, unlike women, a group of whom would demand full political rights in 1794, and insist on being called "Citess," following the example of their French sisters during that nation's revolution.

In 1790, the Federalists finally replaced the 1776 state constitution with a more conservative frame of government that included a Senate, a powerful governor - he had the veto power and could appoint many state officers - and independent judiciary. Pennsylvania's 1790 Constitution also ended the oath that excluded Jews from voting in state elections. The federal Constitution of 1787 stipulated that a new federal district would become the national capital, but as the nation's largest and most centrally located city, Philadelphia from 1790 to 1800 served as the capital of both Pennsylvania and the federal government. In 1790, in return for approving Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton's financial program, southern delegates secured a federal district as of 1800, the future Washington, D.C.

a more conservative frame of government that included a Senate, a powerful governor - he had the veto power and could appoint many state officers - and independent judiciary. Pennsylvania's 1790 Constitution also ended the oath that excluded Jews from voting in state elections. The federal Constitution of 1787 stipulated that a new federal district would become the national capital, but as the nation's largest and most centrally located city, Philadelphia from 1790 to 1800 served as the capital of both Pennsylvania and the federal government. In 1790, in return for approving Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton's financial program, southern delegates secured a federal district as of 1800, the future Washington, D.C.

For most of that decade, a period known as the Federalist era, Pennsylvania and national politics were inextricably intertwined and exceptionally tumultuous. The state endured two "rebellions" - the Whiskey and Fries - and was a closely contested battleground for the two political parties. It was also the center of the publishing industry that fueled the nationwide disputes. Despite the two uprisings and a presidential election in 1800 that might have resulted in violence had John Adams won, Pennsylvania Governor

Fries - and was a closely contested battleground for the two political parties. It was also the center of the publishing industry that fueled the nationwide disputes. Despite the two uprisings and a presidential election in 1800 that might have resulted in violence had John Adams won, Pennsylvania Governor  Thomas McKean let it be known that he would muster the state militia to install Jefferson in the White House - both the nation and the state emerged peaceful and prosperous as the nineteenth century began.

Thomas McKean let it be known that he would muster the state militia to install Jefferson in the White House - both the nation and the state emerged peaceful and prosperous as the nineteenth century began.

As the American Revolution dragged on, the new Pennsylvania constitution became increasingly unpopular

At first, Joseph Reed, George Bryan,

Examples of the divisions within the state abounded. In 1779,

Pennsylvanians refusal to pay taxes and the inability of the government to collect them accompanied the federal government's failure to raise money. In 1781, state president Joseph Reed had to pardon the troops and promise them payment, which they received later in the decade in the form of western lands. In 1783, rambunctious troops chased Congress out of Philadelphia. Nor could either the federal or state government protect settlers in western Pennsylvania. In 1782, Indians burned Hanna's Town, the intended capital of Westmoreland County.

After 1786, the Republicans assumed control of Pennsylvania government, and changed their name to Federalists. Led by

On May 25, 1787, fifty-five delegates from twelve states (the exception being Rhode Island) convened at the Pennsylvania State House, called to amend the Articles, but it was an open secret that they, and the Congress and state legislatures that authorized the meeting, intended to create a new frame of government. The new constitution they drafted was based on the principle of "federalism," or the division of powers between the state and national levels. The new federal government would consist of three branches: a legislature, which made the law; an executive, which enforced the law; and a judiciary, which interpreted the law. To prevent an excessive accumulation of power within any single branch, the framers created a system of checks and balances among the three branches.

Pennsylvania and its eight delegates - the most of any state - played an important role in framing and adopting the Constitution. Living in a state where the failure to balance diverse ethnic, religious, class, and geographic interests had led to frontier warfare and the nation's most convulsive internal revolution, they led the way in achieving compromise among delegates who disagreed on the shape of the new government. James Wilson argued successfully that immigrants be granted equal citizenship: he and two other Pennsylvania delegates, Robert Morris and Thomas Fitzsimmons, were immigrants themselves.

Sympathetic to the needs of both large and small states,

Dickinson's success appears in the fact that Delaware and Pennsylvania were the first two states to approve the constitution. Pennsylvania's approval, however, was problematic. The state legislatures could not vote on the Constitution; they had to call ratifying conventions open to all adult males, thus simulating the agreement required by philosopher John Locke for people to leave a state of nature and form a government. But the Pennsylvania state legislature required a two-thirds majority to meet, legally, and the Federalists (former Republicans) lacked the two representatives they needed to muster such a majority.

The anti-Federalists (former Constitutionalists) decided to simply not show up. So a Federalist crowd sought out two of these assemblymen, physically carried them into the legislative chamber, and kept them there until the vote passed. Pennsylvania's convention then voted 2-1 to approve the Constitution, but anti-federalists Robert Whitehill and William Findley first voiced what would become the main objection to the document: it lacked security for popular rights.

While the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were working on a new frame of national government, people excluded from political life in Pennsylvania organized to obtain equal rights and call the nation's leading statesmen's attention to their plight. In 1787, Philadelphia's Jewish congregation,

In 1790, the Federalists finally replaced the 1776 state constitution with

For most of that decade, a period known as the Federalist era, Pennsylvania and national politics were inextricably intertwined and exceptionally tumultuous. The state endured two "rebellions" - the Whiskey and