![header=[Marker Text] body=[Established in 1787 under the leadership of Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, this organization fostered identity, leadership, and unity among Blacks and became the forerunner of the first African-American churches in this city.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-27B-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h8z0-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Free African Society [New Nation]

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

6th and Lombard Sts., Philadelphia

Behind the Marker

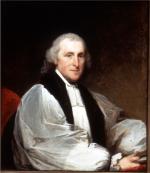

In the years that followed the end of the American Revolution, black Philadelphians continued to attend white churches. But seating restrictions and exclusion from services inhibited their ability to worship. In May of 1787, the same month in which the Constitutional Convention met, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen founded the Free African Society the first benevolent society organized by African Americans in the United States. Created to benefit African Americans who "lived a sober and orderly life," the original seven members agreed to pay one shilling a month into a fund that would provide a small stipend if they or their wives, widows, or children fell into poverty, provided "this necessity is not brought on them by their own imprudence." In setting up the society, they thanked William White, the first bishop of Pennsylvania's Episcopal Church, "whose early assistance and useful remarks we found truly profitable." White's friendly attitude explains why many blacks, who were welcome to sit with their masters in the town's Episcopal churches even as slaves, never left the Episcopal Church.

Free African Society the first benevolent society organized by African Americans in the United States. Created to benefit African Americans who "lived a sober and orderly life," the original seven members agreed to pay one shilling a month into a fund that would provide a small stipend if they or their wives, widows, or children fell into poverty, provided "this necessity is not brought on them by their own imprudence." In setting up the society, they thanked William White, the first bishop of Pennsylvania's Episcopal Church, "whose early assistance and useful remarks we found truly profitable." White's friendly attitude explains why many blacks, who were welcome to sit with their masters in the town's Episcopal churches even as slaves, never left the Episcopal Church.

Founded in 1794, St. Thomas' Episcopal, with Absalom Jones installed as its priest, would become Philadelphia's first black church. Richard Allen, a Methodist, felt less welcome in the Methodists' St. George's Church, where blacks were only allowed to hold services at 5 a.m. So he founded "Mother Bethel" later in 1794, the nation's first African Methodist Episcopal Church.

"Mother Bethel" later in 1794, the nation's first African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In years since passage of the Pennsylvania gradual abolition law of 1780, Philadelphia had become home to the nation's largest free black community. Racism, however, continued to bar African Americans from most of the city's churches, schools, and even cemeteries. The Free African Society thus took it upon itself to open schools, churches, and to buy a graveyard from the city.

The Society was also deeply concerned, as its preamble states, with moral behavior. Jones and Allen recognized that clean living and moral behavior were essential both to the health and prosperity of their growing community and to the ongoing struggle to combat the racism of white Philadelphians.

In a selfless act that would eventually lead to its own dissolution, the Free African Society also demonstrated the humanitarian commitment of Philadelphia's African Americans to the early republic during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. At first, believing Dr. Benjamin Rush's opinion that they were immune from the disease, members of the Free African Society and other black Philadelphians stayed in town when many whites left, serving as nurses throughout the infected areas of the city and as carters who removed victims of the plague from their households to local cemeteries.

Benjamin Rush's opinion that they were immune from the disease, members of the Free African Society and other black Philadelphians stayed in town when many whites left, serving as nurses throughout the infected areas of the city and as carters who removed victims of the plague from their households to local cemeteries.

They continued to help even after black volunteers became infected by the score. Soon, however, publisher Matthew Carey's popular A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, which quickly went through four printings, blamed them for profiting from the disaster by charging excessively for their services. Jones and Allen replied with their own pamphlet, showing that blacks frequently went unpaid and sometimes advanced their own money for medical supplies.

pamphlet, showing that blacks frequently went unpaid and sometimes advanced their own money for medical supplies.

They also argued that there was nothing wrong with blacks exercising what whites had always considered a natural right - engaging in labor, and dangerous labor at that - to earn the best living they could. In fact, blacks had demonstrated their civic virtue, for they had stayed in the city when President Washington and most of the government left town to avoid an epidemic that killed more than 4,000 of the city's 40,000 to 50,000 people.

In the end, the heroic efforts of the Free African Society resulted in its financial ruin. Having accumulated a debt of £177 due to the expenses of bedding and moving victims of the yellow fever, the Society was forced to close at the end of the year. But its legacy would continue through the leadership of the city's African American churches and a thriving black community, which in 1800 numbered over 6,400 people, nearly 44 percent of Pennsylvania's total black population. Philadelphia County's free black population would grow to more than 14,500 in 1830 and close to 20,000 in 1840, making it the largest in the nation.

Founded in 1794, St. Thomas' Episcopal, with Absalom Jones installed as its priest, would become Philadelphia's first black church. Richard Allen, a Methodist, felt less welcome in the Methodists' St. George's Church, where blacks were only allowed to hold services at 5 a.m. So he founded

In years since passage of the Pennsylvania gradual abolition law of 1780, Philadelphia had become home to the nation's largest free black community. Racism, however, continued to bar African Americans from most of the city's churches, schools, and even cemeteries. The Free African Society thus took it upon itself to open schools, churches, and to buy a graveyard from the city.

The Society was also deeply concerned, as its preamble states, with moral behavior. Jones and Allen recognized that clean living and moral behavior were essential both to the health and prosperity of their growing community and to the ongoing struggle to combat the racism of white Philadelphians.

In a selfless act that would eventually lead to its own dissolution, the Free African Society also demonstrated the humanitarian commitment of Philadelphia's African Americans to the early republic during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. At first, believing Dr.

They continued to help even after black volunteers became infected by the score. Soon, however, publisher Matthew Carey's popular A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, which quickly went through four printings, blamed them for profiting from the disaster by charging excessively for their services. Jones and Allen replied with their own

They also argued that there was nothing wrong with blacks exercising what whites had always considered a natural right - engaging in labor, and dangerous labor at that - to earn the best living they could. In fact, blacks had demonstrated their civic virtue, for they had stayed in the city when President Washington and most of the government left town to avoid an epidemic that killed more than 4,000 of the city's 40,000 to 50,000 people.

In the end, the heroic efforts of the Free African Society resulted in its financial ruin. Having accumulated a debt of £177 due to the expenses of bedding and moving victims of the yellow fever, the Society was forced to close at the end of the year. But its legacy would continue through the leadership of the city's African American churches and a thriving black community, which in 1800 numbered over 6,400 people, nearly 44 percent of Pennsylvania's total black population. Philadelphia County's free black population would grow to more than 14,500 in 1830 and close to 20,000 in 1840, making it the largest in the nation.

Beyond the Marker

![Frontpiece, <i>A narrative of the proceedings of the black people during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793 ; and a refutation of some censures, thrown upon them in some late publications,</i> / by A.J. [Absolom Jones] and R.A. [Richard Allen]. Frontpiece, <i>A narrative of the proceedings of the black people during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793 ; and a refutation of some censures, thrown upon them in some late publications,</i> / by A.J. [Absolom Jones] and R.A. [Richard Allen].](cache/small/1-2-984-25-ExplorePAHistory-a0j6s4-a_349.jpg)