![header=[Marker Text] body=[Grammar school founded in 1773. College chartered in 1783, and named for John Dickinson. "Old West," built 1804, was designed by Benjamin H. Latrobe, architect of the national Capitol.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-27A-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h8y8-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

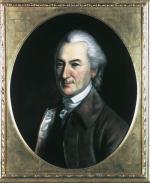

John Dickinson (Dickinson College) New Nation

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Cumberland

Marker Location:

W High St., near 74N intersection at campus, Carlisle

Dedication Date:

July 1, 1947

Behind the Marker

In 1776, John Dickinson achieved no small notoriety for his opposition to the Declaration of Independence, but he more than made up for it with his extensive public service in the following years. From 1776 to 1779 he served as colonel of the Philadelphia militia's first battalion of Associators. Moving to Delaware, he in the early 1780s, served first as governor of Delaware, and then as President of Pennsylvania - he owned property in both states. His extensive contributions and efforts to found a new college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, led to its being named after him when it opened its doors in 1783.

Dickinson also played a crucial role in framing the Federal Constitution. At the Constitutional Convention, he realized early on that "mutual concessions" would be required if the large states and small states were to agree on a document. Having governed both Delaware and Pennsylvania, he argued that each state should be equally represented in one house, and representation in the other house based on how much a state paid in federal taxes.(He soon came to see the wisdom of changing this to population: the federal government has never levied direct taxes on states.)

He also argued successfully against the power of the federal government to veto state legislation, a measure that some delegates favored. He pushed to have the president elected by the people, insisting that his selection by the national legislature would form "an improper dependence and connection." (At first, some state legislatures chose the presidential electors, but all the states ultimately adopted Dickinson's position.) Like his elder colleague Benjamin Franklin, Dickinson was a consistent advocate for compromise at the convention, willing to surrender his own opinion in the interest of producing a final document acceptable to all the delegates.

Benjamin Franklin, Dickinson was a consistent advocate for compromise at the convention, willing to surrender his own opinion in the interest of producing a final document acceptable to all the delegates.

Once the constitution was drafted, Dickinson lent his pen to the cause of ratification. His nine "Fabius" essays, published in 1788 after Delaware and Pennsylvania had ratified the Constitution but most states had not, were written in a more down-to-earth style than the Federalist Papers by Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, which are more famous today. George Washington praised Dickinson for the mastery of his subject and the easy-to-understand manner in which he presented it. Dickinson's culminating argument illustrates this eloquence:

Dickinson retired to his much beloved estate in Jones Neck, Delaware, for most of the next eight years. But when John Jay negotiated a treaty with Britain in 1794 that failed to guarantee that the British fleet would not interrupt American shipping, "Fabius" once again entered the political arena. A firm supporter of the French Revolution, even after the execution of Louis XVI, Dickinson argued that attacks by Britain and other European powers had forced France to defend itself. He even wrote an ode praising the French Revolution, much as a quarter-century before he had penned the "Liberty Song" that inspired American revolutionaries.

"Liberty Song" that inspired American revolutionaries.

Although he was not a Quaker, Dickinson was buried in a Friends' cemetery on his death in 1808. From moderate revolutionary to a staunch supporter of revolutionary France and Thomas Jefferson, Dickinson's political odyssey was uniquely his own.

To learn more about John Dickinson's actions during the American Revolution click here.

here.

Dickinson also played a crucial role in framing the Federal Constitution. At the Constitutional Convention, he realized early on that "mutual concessions" would be required if the large states and small states were to agree on a document. Having governed both Delaware and Pennsylvania, he argued that each state should be equally represented in one house, and representation in the other house based on how much a state paid in federal taxes.(He soon came to see the wisdom of changing this to population: the federal government has never levied direct taxes on states.)

He also argued successfully against the power of the federal government to veto state legislation, a measure that some delegates favored. He pushed to have the president elected by the people, insisting that his selection by the national legislature would form "an improper dependence and connection." (At first, some state legislatures chose the presidential electors, but all the states ultimately adopted Dickinson's position.) Like his elder colleague

Once the constitution was drafted, Dickinson lent his pen to the cause of ratification. His nine "Fabius" essays, published in 1788 after Delaware and Pennsylvania had ratified the Constitution but most states had not, were written in a more down-to-earth style than the Federalist Papers by Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, which are more famous today. George Washington praised Dickinson for the mastery of his subject and the easy-to-understand manner in which he presented it. Dickinson's culminating argument illustrates this eloquence:

"Our government under the proposed confederation, will be guarded by a repetition of the strongest cautions against excesses. In the Senate, the sovereignties of the several states will be equally represented; in the House of Representatives, the people of the whole union will be equally represented; and in the president, and the federal independent judges, so much concerned with the execution of the laws, and in the determination of their constitutionality, the sovereignties of the several states and the people of the whole union, may be considered as conjointly represented.

Where was there ever and where is there now upon the face of the earth, a government so diversified and attempered? If a work formed with so much deliberation, so respectful and affectionate an attention to the interests, feelings, and sentiments of all United America, will not satisfy, what would satisfyall United America?"

Dickinson retired to his much beloved estate in Jones Neck, Delaware, for most of the next eight years. But when John Jay negotiated a treaty with Britain in 1794 that failed to guarantee that the British fleet would not interrupt American shipping, "Fabius" once again entered the political arena. A firm supporter of the French Revolution, even after the execution of Louis XVI, Dickinson argued that attacks by Britain and other European powers had forced France to defend itself. He even wrote an ode praising the French Revolution, much as a quarter-century before he had penned the

Although he was not a Quaker, Dickinson was buried in a Friends' cemetery on his death in 1808. From moderate revolutionary to a staunch supporter of revolutionary France and Thomas Jefferson, Dickinson's political odyssey was uniquely his own.

To learn more about John Dickinson's actions during the American Revolution click