Chapter One: Spoken Into Existence: From Settlement to Independence

In 1793, Supreme Court Justice  James Wlson the Carlisle lawyer who served in the Continental Congress and then as a Pennsylvania representative during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, claimed that the people "spoke [the United States] into existence."

James Wlson the Carlisle lawyer who served in the Continental Congress and then as a Pennsylvania representative during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, claimed that the people "spoke [the United States] into existence."  Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphia doctor who signed the Declaration of Independence, shared the same belief, writing in 1793 that American independence could be attributed "as much to the power of eloquence as to the sword."

Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphia doctor who signed the Declaration of Independence, shared the same belief, writing in 1793 that American independence could be attributed "as much to the power of eloquence as to the sword."

Pennsylvania, like the United States itself, was born of an idea. From the beginning, the colony's identity and its meaning took shape through the power of words. To attract colonists to his "Holy Experiment" -a land where people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds could flourish in a land of peace and plenty- William Penn published open letters in Great Britain and on the Continent. Penn's promotional tracts were soon followed by other accounts of the new colony, written by

open letters in Great Britain and on the Continent. Penn's promotional tracts were soon followed by other accounts of the new colony, written by  Francis Daniel Pastorius,

Francis Daniel Pastorius,  Thomas Budd,

Thomas Budd,  Gabriel Thomas, and other new arrivals.

Gabriel Thomas, and other new arrivals.

Not all of these accounts were flattering. After returning to England, former indentured servant William Moraley in 1729 published a bitter account of his unhappy days in Pennsylvania. In 1756, Gottlieb Mittelberger warned Germans of the extreme hardships of the voyage to Pennsylvania and of life as a

bitter account of his unhappy days in Pennsylvania. In 1756, Gottlieb Mittelberger warned Germans of the extreme hardships of the voyage to Pennsylvania and of life as a  poor "redemptioner" in Penn's colony. Distressed by the presence of slavery in Penn's "Holy Experiment," four German Quakers in 1688 penned the

poor "redemptioner" in Penn's colony. Distressed by the presence of slavery in Penn's "Holy Experiment," four German Quakers in 1688 penned the  first formal protest against slavery written in North America.

first formal protest against slavery written in North America.

From the earliest days of settlement, Pennsylvania colonists also produced a rising volume of religious publications, including a prolific output of printed material to meet the devotional needs of the Commonwealth's Quakers and growing profusion of other denominations. Here, Penn also took the lead, authoring more than 400 maxims for leading a good and holy life, which he published as "Some Fruits of Solitude" in 1682.

William Bradford, who started the first printing press in the Commonwealth in 1685, Benjamin Franklin, and other Philadelphia printers published religious works by European and American clerics, including German mystic Johannes Kelpius, Presbyterian evangelist

Johannes Kelpius, Presbyterian evangelist  Gilbert Tennent, charismatic English preacher George Whitefield, whose six trips to the colonies between 1739 and 1771 made him the first inter-colonial celebrity, and William Smith, who defended the Anglican church.

Gilbert Tennent, charismatic English preacher George Whitefield, whose six trips to the colonies between 1739 and 1771 made him the first inter-colonial celebrity, and William Smith, who defended the Anglican church.

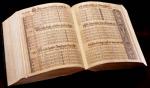

Germans, who represented about a third of Pennsylvania's colonial population by the mid-1700s, proved an eager market for printed works, including almanacs, powwow books, and travel accounts. In 1738, Christopher Saur opened the colony's first German-language printing shop, in Germantown. Over the next fifty years, Saur published the first German-language hymnals, almanacs, and Bible in North America. In the 1740s, the monks at Ephrata Cloister set up their own printing press, paper mill, and book bindery to publish the great Thieleman Van Bragt's Martyr Book, a massive folio of 1,512 pages; the hymns of Conrad Beissel, their spiritual leader; and religious tracts by Moravian leader Count Zinzendorf, calling for the uniting of all the Germans sect in America.

Ephrata Cloister set up their own printing press, paper mill, and book bindery to publish the great Thieleman Van Bragt's Martyr Book, a massive folio of 1,512 pages; the hymns of Conrad Beissel, their spiritual leader; and religious tracts by Moravian leader Count Zinzendorf, calling for the uniting of all the Germans sect in America.

The Moravians who settled in Lehigh Valley were deeply committed to spreading word of the Gospel. The sole Christian denomination in which every man and women was considered a missionary, the Moravians were active in America, Africa, and Asia during the eighteenth century. In the late 1700's Moravian missionary David Zeisberger published several works in the Delaware tongue, including a bilingual spelling book and translations of hymns from German and English hymnbooks of the Moravian Church. Missionary

David Zeisberger published several works in the Delaware tongue, including a bilingual spelling book and translations of hymns from German and English hymnbooks of the Moravian Church. Missionary  John Heckewelder's History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations (1818) remains a classic of American ethnography.

John Heckewelder's History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations (1818) remains a classic of American ethnography.

The German-language press would remain active in Pennsylvania, publishing a broad range of materials-including an account of the Lewis and Clark expedition-into the early 1800s. After the Common School Act of 1834 mandated English-language public education for all the Commonwealth's children -a development fiercely resisted by many Pennsylvania Germans- the German-language presses fell into disuse.

Lewis and Clark expedition-into the early 1800s. After the Common School Act of 1834 mandated English-language public education for all the Commonwealth's children -a development fiercely resisted by many Pennsylvania Germans- the German-language presses fell into disuse.

Religious items, along with official documents printed by the government, were the most frequent publications in early America. In the 1700s, however, the role of printing expanded as writers of essays, newspaper articles, and almanacs entered "the public sphere." No longer issued primarily by religious and political authorities, information now became subject to debate among an increasingly literature public - albeit one that was mostly white, male, and middle and upper-class. The validity of someone's arguments and the cogency of their style-many items were published anonymously-began to matter more than the official position of the writer.

In the mid-1700s, Pennsylvania became a center of publication, in part because it boasted the first paper mill in the thirteen colonies, started by William Rittenhouse in 1690 at Rittenhouse Town, still preserved as a living museum in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park. Printing was a small industry in early America: there were only three English and three German-language printers in colonial Pennsylvania. The newspapers that emerged from their presses, however, were distributed and shared throughout the colony at coffee houses, taverns, and the homes of subscribers.

Rittenhouse Town, still preserved as a living museum in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park. Printing was a small industry in early America: there were only three English and three German-language printers in colonial Pennsylvania. The newspapers that emerged from their presses, however, were distributed and shared throughout the colony at coffee houses, taverns, and the homes of subscribers.

Pennsylvania will be forever identified with Benjamin Franklin, the greatest American printer and writer of the colonial era. Only a year after arriving in Philadelphia from Boston in 1723, the eighteen-year-old Franklin set up what soon became the most successful print shop in North America. From his extraordinary mind, pen, and press came an outpouring of practical wisdom, political commentary, economic advice, and scientific observations unparalleled in American history. In 1729, Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith took over The Pennsylvania Gazette, the second newspaper in Pennsylvania. (Andrew Bradford had started the first, The American Weekly Mercury, in 1718.)

Benjamin Franklin, the greatest American printer and writer of the colonial era. Only a year after arriving in Philadelphia from Boston in 1723, the eighteen-year-old Franklin set up what soon became the most successful print shop in North America. From his extraordinary mind, pen, and press came an outpouring of practical wisdom, political commentary, economic advice, and scientific observations unparalleled in American history. In 1729, Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith took over The Pennsylvania Gazette, the second newspaper in Pennsylvania. (Andrew Bradford had started the first, The American Weekly Mercury, in 1718.)

The Gazette soon became the Commonwealth's most important newspaper. From 1732 to 1758, Franklin also produced America's best-selling Poor Richard's Almanack, from which he extracted the economic wisdom compiled into his best-selling The Way to Wealth (1754). Franklin's writings would also provide the world its first glimpse of the new American; the practical, democratic, independent, civic-minded, and self-made man. Written between 1771 and 1790, his autobiography is one of the most celebrated and enduring works of American literature. It has served as the great model of American autobiographies from his day to our own.

In the mid-1700s, Philadelphia emerged as the largest, most cosmopolitan city in Britain's American colonies-and as their cultural and scientific center. Here, in 1731, Franklin and his associates organized the Library Company, the colonies' first lending library. Four decades later, in 1771, the American Philosophical Society, modeled on Great Britain's Royal Society as a clearinghouse for scientific and practical knowledge, published David Rittenhouse's calculations on the transit of Venus in the first printing of its Transactions. The oldest continuous publication in the United States, this journal is still in press today. Here, too, William Smith, provost of the College of Philadelphia [today's University of Pennsylvania] in 1757 published the short-lived The American Magazine, the first periodical to feature the work of American authors.

David Rittenhouse's calculations on the transit of Venus in the first printing of its Transactions. The oldest continuous publication in the United States, this journal is still in press today. Here, too, William Smith, provost of the College of Philadelphia [today's University of Pennsylvania] in 1757 published the short-lived The American Magazine, the first periodical to feature the work of American authors.

Philadelphia also became a center of the political agitation and a war of words during the period of the French and Indian War. In 1754, Franklin created "JOIN OR DIE," the first political cartoon in British North America, which depicted the colonies as the separated parts of a snake. The Paxton Boys' massacre of twenty peaceful Conestoga Indians in December 1763 fueled publication of an unprecedented fifty-eight pamphlets criticizing or supporting the Boys, the governor, the assembly, and Benjamin Franklin, who was accused of manipulating events in the hope of turning Pennsylvania into a royal government with himself as governor.

Conestoga Indians in December 1763 fueled publication of an unprecedented fifty-eight pamphlets criticizing or supporting the Boys, the governor, the assembly, and Benjamin Franklin, who was accused of manipulating events in the hope of turning Pennsylvania into a royal government with himself as governor.

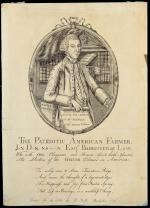

Philadelphia continued to be a leading publication center during the days of the American Revolution. Here, in 1768, John Dickinson made his case for the rights of Englishmen in America in his influential

John Dickinson made his case for the rights of Englishmen in America in his influential  Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. In 1776, firebrand Thomas Payne wrote

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. In 1776, firebrand Thomas Payne wrote  Common Sense the best-selling rallying cry for separation from England. Later that year, a committee of the Second Continental Congress, led by Thomas Jefferson, penned the Declaration of Independence, and members of Congress drafted the Articles of Confederation, the new nation's first frame of government.

Common Sense the best-selling rallying cry for separation from England. Later that year, a committee of the Second Continental Congress, led by Thomas Jefferson, penned the Declaration of Independence, and members of Congress drafted the Articles of Confederation, the new nation's first frame of government.

The war itself drove the penning and publication of an outpouring of words-poems, plays, polemics, narratives of battles and massacres, political and legal disquisitions, and more-to inspire patriotism, legitimate the revolution, organize governments, and give voice to a nation. And through it all, Philadelphia's authors and printers produced more words and more pages than their counterparts in any other city in the new nation.

Pennsylvania, like the United States itself, was born of an idea. From the beginning, the colony's identity and its meaning took shape through the power of words. To attract colonists to his "Holy Experiment" -a land where people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds could flourish in a land of peace and plenty- William Penn published

Not all of these accounts were flattering. After returning to England, former indentured servant William Moraley in 1729 published a

From the earliest days of settlement, Pennsylvania colonists also produced a rising volume of religious publications, including a prolific output of printed material to meet the devotional needs of the Commonwealth's Quakers and growing profusion of other denominations. Here, Penn also took the lead, authoring more than 400 maxims for leading a good and holy life, which he published as "Some Fruits of Solitude" in 1682.

William Bradford, who started the first printing press in the Commonwealth in 1685, Benjamin Franklin, and other Philadelphia printers published religious works by European and American clerics, including German mystic

Germans, who represented about a third of Pennsylvania's colonial population by the mid-1700s, proved an eager market for printed works, including almanacs, powwow books, and travel accounts. In 1738, Christopher Saur opened the colony's first German-language printing shop, in Germantown. Over the next fifty years, Saur published the first German-language hymnals, almanacs, and Bible in North America. In the 1740s, the monks at

The Moravians who settled in Lehigh Valley were deeply committed to spreading word of the Gospel. The sole Christian denomination in which every man and women was considered a missionary, the Moravians were active in America, Africa, and Asia during the eighteenth century. In the late 1700's Moravian missionary

The German-language press would remain active in Pennsylvania, publishing a broad range of materials-including an account of the

Religious items, along with official documents printed by the government, were the most frequent publications in early America. In the 1700s, however, the role of printing expanded as writers of essays, newspaper articles, and almanacs entered "the public sphere." No longer issued primarily by religious and political authorities, information now became subject to debate among an increasingly literature public - albeit one that was mostly white, male, and middle and upper-class. The validity of someone's arguments and the cogency of their style-many items were published anonymously-began to matter more than the official position of the writer.

In the mid-1700s, Pennsylvania became a center of publication, in part because it boasted the first paper mill in the thirteen colonies, started by William Rittenhouse in 1690 at

Pennsylvania will be forever identified with

The Gazette soon became the Commonwealth's most important newspaper. From 1732 to 1758, Franklin also produced America's best-selling Poor Richard's Almanack, from which he extracted the economic wisdom compiled into his best-selling The Way to Wealth (1754). Franklin's writings would also provide the world its first glimpse of the new American; the practical, democratic, independent, civic-minded, and self-made man. Written between 1771 and 1790, his autobiography is one of the most celebrated and enduring works of American literature. It has served as the great model of American autobiographies from his day to our own.

In the mid-1700s, Philadelphia emerged as the largest, most cosmopolitan city in Britain's American colonies-and as their cultural and scientific center. Here, in 1731, Franklin and his associates organized the Library Company, the colonies' first lending library. Four decades later, in 1771, the American Philosophical Society, modeled on Great Britain's Royal Society as a clearinghouse for scientific and practical knowledge, published

Philadelphia also became a center of the political agitation and a war of words during the period of the French and Indian War. In 1754, Franklin created "JOIN OR DIE," the first political cartoon in British North America, which depicted the colonies as the separated parts of a snake. The Paxton Boys' massacre of twenty peaceful

Philadelphia continued to be a leading publication center during the days of the American Revolution. Here, in 1768,

The war itself drove the penning and publication of an outpouring of words-poems, plays, polemics, narratives of battles and massacres, political and legal disquisitions, and more-to inspire patriotism, legitimate the revolution, organize governments, and give voice to a nation. And through it all, Philadelphia's authors and printers produced more words and more pages than their counterparts in any other city in the new nation.