![header=[Marker Text] body=[Surviving restored buildings of the Seventh Day Baptist community founded by Conrad Beissel. Original buildings erected between 1735 and 1749. Administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-4A-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a2y5-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Ephrata Cloister

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Lancaster

Marker Location:

At the site on US 322, Ephrata

Behind the Marker

Conrad Beissel, the founder of the Ephrata Cloister, was born in 1691, at the end of nearly a century of wars that devastated his homeland. Both of Beissel's parents had died by the time he was eight. He was raised by an uncle in a neighboring town, with the aid of his older brothers and sisters. He probably received little formal school training, but was taught the trade of a baker.

Beissel escaped from poverty when a relative apprenticed him to a baker in his hometown of Eberbach, a town in the German state of Baden-Wurttemberg. From this man Beissel learned the baking trade, and how to play the fiddle, awakening in him what would become a lifelong, passionate love of music.

As Beissel became a journeyman baker and began to ply his trade in neighboring towns, he fell under the influence of a charismatic group of pietists, or religious purists, who advocated radical church reforms. Arrested in Heidelberg for refusing to attend the state-affiliated Reformed Church, Beissel fled to Westphalia. In 1720, Beissel and a group of friends immigrated to Pennsylvania, joining in a migration that would bring more than five thousand German pietists to Pennsylvania.

Beissel may have hoped to join the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, a small group of celibate hermits led by Johannes Kelpius, who had taken up residence by the banks of the Wissahickon River north of Philadelphia in 1694. Finding only a few monks remaining, he worked briefly in Germantown, the center of German Mennonite life in Penn's colony, before moving to the western frontier of Pennsylvania.

Johannes Kelpius, who had taken up residence by the banks of the Wissahickon River north of Philadelphia in 1694. Finding only a few monks remaining, he worked briefly in Germantown, the center of German Mennonite life in Penn's colony, before moving to the western frontier of Pennsylvania.

In 1724 Beissel joined a new congregation of the German Baptist Brethren and helped to build the Conestoga congregation; however, in 1728, after disagreements with the Germantown elders he left the church. Soon, he was surrounded by a community of followers whom he later organized into married "Householders" and separate "Solitaries" of men and women who embraced his belief in celibacy.

In 1732 Beissel and his followers established a Christian settlement near the banks of the Cocalico Creek in Lancaster County. The community soon became known as "Ephrata," the biblical name of the region around the town of Bethlehem. Those who chose a celibate life within the community resided in a Cloister while married Householders lived on farms in the surrounding area. The Ephrata Cloister was the heart and soul of the community. Here, Brothers and Sisters, clothed in long, hooded, white robes, spent their days in meditation, hard work, and worship under the rigorous tutelage and watchful eyes of their spiritual guide, Beissel.

Both a colorful and controversial leader, Beissel was a stern man, who would preach sermons that lasted for hours. Visitors often described the hard working Brothers and Sisters of the Cloister as thin and pale, wearing long white robes, and going shoeless. Accusations of sexual improprieties circulated, as daughters and even wives from surrounding farms deserted their homes to join the Cloister.

Upon joining the Cloister, each initiate took a new name from the Bible and embraced the ascetic life. Although some followers continued to own personal property, they lived and worshipped in large Germanic buildings constructed by the community. The Brothers and Sisters lived in separate dormitories, in small rooms devoid of comforts. Embracing the belief that becoming too comfortable and settled into a deep relaxed state could possibly leave one open to temptations, each member slept on a hard wooden bench with a block of wood for a pillow.

For all its rigorous asceticism, Ephrata was a busy and prosperous place. The community cultivated an orchard, produced flax, wheat, and other grains, and operated a variety of well-run mills. Everyday chores included basket making, carpentry, cooking, gardening, tending the orchard, making linen, and sewing clothes. Residents were also well known in the surrounding region for their generosity, industriousness, and pacifism. Brothers and Sisters provided bread and flour to the poor. They also started a school for settlers' children, where they taught German language, mathematics, penmanship, and the Old and New Testament. Beissel attracted many followers from the region like Ludwig Hocker, who became the community's school teacher, and Peter Miller, who was trained at the University of Heidelberg in theology and law. Ephrata also drew visitors from Europe eager to learn about the arrangements of cloister life and Beissel's theology.

the arrangements of cloister life and Beissel's theology.

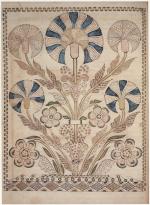

Music was an integral part of worship at the Cloister. Under Beissel's direction the Brothers and Sisters sang hymns in four-part harmony that he and other members had composed. Outsiders who attended services described their music as truly heavenly, like something out of this world. Ever the perfectionist in matters he considered holy, Beissel also prescribed special dietary restrictions on the choir members to purify their voices. The choir sang at a remarkably high pitch that enthralled listeners. The Sisters produced beautifully illuminated manuscripts of the hymns and choral works sung at the Cloister.

The brothers also ran a well-known print shop, using a German-built printing press, and manufactured paper. In the 1740s the community started a complete book publishing business. Their publishing center included authors, production of paper and ink, a press, and book bindery. On their own hand-made linen paper, community members printed books, broadsides, and hymnals. No book was more important among Pennsylvania's German Mennonite immigrants than the Martyrer-Spiegel, (Martyr's Mirror), an encyclopedic chronicle of the death and violence suffered by Anabaptists and other pacifist Christians in Europe.

In the 1740s Brother Peter Miller spent more than three years translating this book from Dutch to German. At 1,512 pages, it was the largest book published in North America prior to 1800. Though the brothers considered this volume "a labor of love," some art historians consider it the greatest product of the colonial bookmakers' art.

At its peak about 1750, the faithful at Ephrata numbered almost 300, consisting of about 80 Solitary and 200 Householders. After Beissel died in 1768, membership declined, but the order continued under the able leadership of Peter Miller until his death in 1796.

The last Solitary member died in 1813. During the American Revolution, the residents of Ephrata, following their pacifist convictions, remained neutral. During the winter of 1777-1778, some of Ephrata's buildings were used as a military hospital by the American army, housing nearly 260 men.

In 1813, after the death of the last celibate residents of the Cloister, the remaining Householders formed the German Seventh Day Baptist Church. Church members continued to use the buildings and worship at Ephrata until 1934, when the congregation at Ephrata closed. The property was then placed under the management of a court appointed receiver. In 1941, the Commonwealth acquired and opened the Cloister as a historic site. Although the faithful are gone, the members of this unusual Christian community have left Pennsylvania, and the nation, a rich legacy of architecture, artwork, literature, and music.

Lord, Remember David and all his afflictions

How he sware unto the Lord, and vowed unto the mighty God of Jacob

Surely I will not come into the tabernacle of my house, nor go up into my bed

I will not give sleep to mine eyes or slumber to mine eyelids

Until I find out a place for the Lord, a habitation for the mighty God of Jacob

Lo, we heard of it at Ephratah: we heard it in the fields of the wood.

-Psalms 132: 1-6.

Surely I will not come into the tabernacle of my house, nor go up into my bed

I will not give sleep to mine eyes or slumber to mine eyelids

Until I find out a place for the Lord, a habitation for the mighty God of Jacob

Lo, we heard of it at Ephratah: we heard it in the fields of the wood.

-Psalms 132: 1-6.

"O blessed solitary life, Where all creation silence keeps"

-From hymn composed by Conrad BeisselConrad Beissel, the founder of the Ephrata Cloister, was born in 1691, at the end of nearly a century of wars that devastated his homeland. Both of Beissel's parents had died by the time he was eight. He was raised by an uncle in a neighboring town, with the aid of his older brothers and sisters. He probably received little formal school training, but was taught the trade of a baker.

Beissel escaped from poverty when a relative apprenticed him to a baker in his hometown of Eberbach, a town in the German state of Baden-Wurttemberg. From this man Beissel learned the baking trade, and how to play the fiddle, awakening in him what would become a lifelong, passionate love of music.

As Beissel became a journeyman baker and began to ply his trade in neighboring towns, he fell under the influence of a charismatic group of pietists, or religious purists, who advocated radical church reforms. Arrested in Heidelberg for refusing to attend the state-affiliated Reformed Church, Beissel fled to Westphalia. In 1720, Beissel and a group of friends immigrated to Pennsylvania, joining in a migration that would bring more than five thousand German pietists to Pennsylvania.

Beissel may have hoped to join the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, a small group of celibate hermits led by

In 1724 Beissel joined a new congregation of the German Baptist Brethren and helped to build the Conestoga congregation; however, in 1728, after disagreements with the Germantown elders he left the church. Soon, he was surrounded by a community of followers whom he later organized into married "Householders" and separate "Solitaries" of men and women who embraced his belief in celibacy.

In 1732 Beissel and his followers established a Christian settlement near the banks of the Cocalico Creek in Lancaster County. The community soon became known as "Ephrata," the biblical name of the region around the town of Bethlehem. Those who chose a celibate life within the community resided in a Cloister while married Householders lived on farms in the surrounding area. The Ephrata Cloister was the heart and soul of the community. Here, Brothers and Sisters, clothed in long, hooded, white robes, spent their days in meditation, hard work, and worship under the rigorous tutelage and watchful eyes of their spiritual guide, Beissel.

Both a colorful and controversial leader, Beissel was a stern man, who would preach sermons that lasted for hours. Visitors often described the hard working Brothers and Sisters of the Cloister as thin and pale, wearing long white robes, and going shoeless. Accusations of sexual improprieties circulated, as daughters and even wives from surrounding farms deserted their homes to join the Cloister.

Upon joining the Cloister, each initiate took a new name from the Bible and embraced the ascetic life. Although some followers continued to own personal property, they lived and worshipped in large Germanic buildings constructed by the community. The Brothers and Sisters lived in separate dormitories, in small rooms devoid of comforts. Embracing the belief that becoming too comfortable and settled into a deep relaxed state could possibly leave one open to temptations, each member slept on a hard wooden bench with a block of wood for a pillow.

For all its rigorous asceticism, Ephrata was a busy and prosperous place. The community cultivated an orchard, produced flax, wheat, and other grains, and operated a variety of well-run mills. Everyday chores included basket making, carpentry, cooking, gardening, tending the orchard, making linen, and sewing clothes. Residents were also well known in the surrounding region for their generosity, industriousness, and pacifism. Brothers and Sisters provided bread and flour to the poor. They also started a school for settlers' children, where they taught German language, mathematics, penmanship, and the Old and New Testament. Beissel attracted many followers from the region like Ludwig Hocker, who became the community's school teacher, and Peter Miller, who was trained at the University of Heidelberg in theology and law. Ephrata also drew visitors from Europe eager to learn about

Music was an integral part of worship at the Cloister. Under Beissel's direction the Brothers and Sisters sang hymns in four-part harmony that he and other members had composed. Outsiders who attended services described their music as truly heavenly, like something out of this world. Ever the perfectionist in matters he considered holy, Beissel also prescribed special dietary restrictions on the choir members to purify their voices. The choir sang at a remarkably high pitch that enthralled listeners. The Sisters produced beautifully illuminated manuscripts of the hymns and choral works sung at the Cloister.

The brothers also ran a well-known print shop, using a German-built printing press, and manufactured paper. In the 1740s the community started a complete book publishing business. Their publishing center included authors, production of paper and ink, a press, and book bindery. On their own hand-made linen paper, community members printed books, broadsides, and hymnals. No book was more important among Pennsylvania's German Mennonite immigrants than the Martyrer-Spiegel, (Martyr's Mirror), an encyclopedic chronicle of the death and violence suffered by Anabaptists and other pacifist Christians in Europe.

In the 1740s Brother Peter Miller spent more than three years translating this book from Dutch to German. At 1,512 pages, it was the largest book published in North America prior to 1800. Though the brothers considered this volume "a labor of love," some art historians consider it the greatest product of the colonial bookmakers' art.

At its peak about 1750, the faithful at Ephrata numbered almost 300, consisting of about 80 Solitary and 200 Householders. After Beissel died in 1768, membership declined, but the order continued under the able leadership of Peter Miller until his death in 1796.

The last Solitary member died in 1813. During the American Revolution, the residents of Ephrata, following their pacifist convictions, remained neutral. During the winter of 1777-1778, some of Ephrata's buildings were used as a military hospital by the American army, housing nearly 260 men.

In 1813, after the death of the last celibate residents of the Cloister, the remaining Householders formed the German Seventh Day Baptist Church. Church members continued to use the buildings and worship at Ephrata until 1934, when the congregation at Ephrata closed. The property was then placed under the management of a court appointed receiver. In 1941, the Commonwealth acquired and opened the Cloister as a historic site. Although the faithful are gone, the members of this unusual Christian community have left Pennsylvania, and the nation, a rich legacy of architecture, artwork, literature, and music.