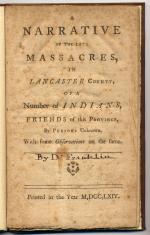

![header=[Marker Text] body=[About one mile eastwards stood the Conestoga Indian Town. Its peaceful Iroquoian inhabitants were visited by William Penn in 1701 who made treaties with them. In 1763 they were ruthlessly massacred by a frontier mob called the "Paxtang Boys." ] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-21D-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h5c7-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Conestoga Indian Town

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Lancaster

Marker Location:

Pa. 999 between Washington boro and Millersville, 200 ft. W of SR 3017

Behind the Marker

In 1700, William Penn promised the Conestoga Indians that they would be treated fairly and equally in his colony and that he and his heirs would always "show themselves [to be] true Friends and Brothers" to them.

The Conestoga took Penn at his word, and for many years, their town served as a center for trade and diplomacy between colonial Pennsylvanians and Indians of the Susquehanna Valley. Even after Conestoga Indian Town's population and significance had declined in Pennsylvania's Indian affairs, its residents still claimed to possess a special relationship with their colonial neighbors rooted in Penn's promise.

All of that ended abruptly in December 1763, when a marauding band of frontiersmen from Harrisburg murdered in cold blood every Conestoga man, woman, and child they could find. When the local magistrates gathered the dead Indians' belongings, they found of copy of Penn's original treaty among them.

The Conestoga Indian Town was one of the many communities of Indian refugees that took root in Pennsylvania during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was formed in the lower Susquehanna Valley by Susquehannock, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, and Conoy Indians on land reserved for them by treaties with the Penn family. Over the years, this diverse population became known collectively as the "Conestoga Indians."

During the 1740s, the Pennsylvania fur trade shifted out of the Susquehanna Valley into the Ohio Country, causing the Conestoga's population and influence to diminish considerably. Pressured by the growing colonial population of Lancaster County, many residents of the town chose to move west with the fur trade. The few Indian families that remained at Conestoga earned a hardscrabble living by farming, hunting, and making brooms and baskets that they sold to their colonial neighbors.

Pontiac's Rebellion, a war that erupted on Pennsylvania frontier in spring 1763, endangered this small community because it was easy prey for colonists seeking retribution for raids by western Indians along the Pennsylvania frontier. In one instance, Connecticut settlers who had moved onto Indian land in the Wyoming Valley were "most cruelly butchered," according to a newspaper account, and found with pitchforks thrust through their bodies. After that Indian attack in the Wyoming Valley, rumors circulated among colonists in the lower Susquehanna Valley that one of the Conestoga Indians, Will Sock, was plotting with others to murder their white neighbors.

On December 14, 1763, about fifty armed colonists from Paxton (near modern Harrisburg) rode into Conestoga. In a dawn attack reminiscent of the Kittanning raid, they burned the homes and murdered the six Indians they found there. Those Indians who had been away from the village at the time of the attack sought refuge in Lancaster, where the city officials locked them inside the workhouse, supposedly the most defensible building in town. On December 27, the Paxton Boys returned, broke into the workhouse, and

Kittanning raid, they burned the homes and murdered the six Indians they found there. Those Indians who had been away from the village at the time of the attack sought refuge in Lancaster, where the city officials locked them inside the workhouse, supposedly the most defensible building in town. On December 27, the Paxton Boys returned, broke into the workhouse, and  murdered the fourteen Indian men, women, and children inside.

murdered the fourteen Indian men, women, and children inside.

The murderous rampage of the Paxton Boys was criticized by some Pennsylvanians, but lauded by others who believed that the eastern Quakers and other Pennsylvanians who controlled the colony's government sympathetic to the Indians had failed to defend the frontier during Pontiac's Rebellion. In early 1764, the Paxton Boys, now several hundred in number, marched toward Philadelphia, intent on killing any Indians and their white protectors that they found there. Benjamin Franklin rode over to them and convinced the Paxton Boys to return home without further violence, but no one was ever arrested or tried for the crimes committed at Conestoga and Lancaster.

sympathetic to the Indians had failed to defend the frontier during Pontiac's Rebellion. In early 1764, the Paxton Boys, now several hundred in number, marched toward Philadelphia, intent on killing any Indians and their white protectors that they found there. Benjamin Franklin rode over to them and convinced the Paxton Boys to return home without further violence, but no one was ever arrested or tried for the crimes committed at Conestoga and Lancaster.

"But the Wickedness cannot be covered, the Guilt will lie on the whole Land, till Justice is done on the Murderers. THE BLOOD OF THE INNOCENT WILL CRY TO HEAVEN FOR VENGEANCE."

-Benjamin Franklin on the Paxton Boys' Massacre

In 1700, William Penn promised the Conestoga Indians that they would be treated fairly and equally in his colony and that he and his heirs would always "show themselves [to be] true Friends and Brothers" to them.

The Conestoga took Penn at his word, and for many years, their town served as a center for trade and diplomacy between colonial Pennsylvanians and Indians of the Susquehanna Valley. Even after Conestoga Indian Town's population and significance had declined in Pennsylvania's Indian affairs, its residents still claimed to possess a special relationship with their colonial neighbors rooted in Penn's promise.

All of that ended abruptly in December 1763, when a marauding band of frontiersmen from Harrisburg murdered in cold blood every Conestoga man, woman, and child they could find. When the local magistrates gathered the dead Indians' belongings, they found of copy of Penn's original treaty among them.

The Conestoga Indian Town was one of the many communities of Indian refugees that took root in Pennsylvania during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was formed in the lower Susquehanna Valley by Susquehannock, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, and Conoy Indians on land reserved for them by treaties with the Penn family. Over the years, this diverse population became known collectively as the "Conestoga Indians."

During the 1740s, the Pennsylvania fur trade shifted out of the Susquehanna Valley into the Ohio Country, causing the Conestoga's population and influence to diminish considerably. Pressured by the growing colonial population of Lancaster County, many residents of the town chose to move west with the fur trade. The few Indian families that remained at Conestoga earned a hardscrabble living by farming, hunting, and making brooms and baskets that they sold to their colonial neighbors.

Pontiac's Rebellion, a war that erupted on Pennsylvania frontier in spring 1763, endangered this small community because it was easy prey for colonists seeking retribution for raids by western Indians along the Pennsylvania frontier. In one instance, Connecticut settlers who had moved onto Indian land in the Wyoming Valley were "most cruelly butchered," according to a newspaper account, and found with pitchforks thrust through their bodies. After that Indian attack in the Wyoming Valley, rumors circulated among colonists in the lower Susquehanna Valley that one of the Conestoga Indians, Will Sock, was plotting with others to murder their white neighbors.

On December 14, 1763, about fifty armed colonists from Paxton (near modern Harrisburg) rode into Conestoga. In a dawn attack reminiscent of the

The murderous rampage of the Paxton Boys was criticized by some Pennsylvanians, but lauded by others who believed that the eastern Quakers and other Pennsylvanians who controlled the colony's government

Beyond the Marker