Chapter 1: Colonial Encounters

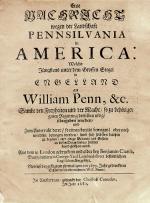

"The air is sweet and clear," proprietor William Penn wrote potential colonists not long after landing in  Philadelphia in 1682; "the heavens serene, like the southern parts of France,

Philadelphia in 1682; "the heavens serene, like the southern parts of France, rarely overcast" Extolling the natural abundance of his "Holy Experiment," Penn offered a detailed assessment of the flora and fauna, the outlines of his great city, and the nature of social life. His was a bright refrain, meant as much to invite the blessings of Providence as to captivate future settlers.

rarely overcast" Extolling the natural abundance of his "Holy Experiment," Penn offered a detailed assessment of the flora and fauna, the outlines of his great city, and the nature of social life. His was a bright refrain, meant as much to invite the blessings of Providence as to captivate future settlers.

Long before Penn and other Europeans imagined Pennsylvania as a haven, a vast North American migration brought hundreds of thousands of American Indians into the Mid-Atlantic region. Not much is known of Pennsylvania's earliest migrants, but simple tools, pieces of pottery, and other evidence of human habitation dating back 14,000 years or more have been found at Meadowcroft Rockshelter in southwestern Pennsylvania, one of the oldest sites of human habitation on the North American continent. Over centuries, different tribal societies formed and flourished, each with their own shifting alliances, customs, and spiritual traditions.

Meadowcroft Rockshelter in southwestern Pennsylvania, one of the oldest sites of human habitation on the North American continent. Over centuries, different tribal societies formed and flourished, each with their own shifting alliances, customs, and spiritual traditions.

By the eighteenth century, a network of overland pathways linked great Indian villages with smaller settlements throughout Pennsylvania's mountains and valleys. These included the Great Shamokin Path, which stretched through the wilderness of the upper Susquehanna River to the Allegheny River, and the

Great Shamokin Path, which stretched through the wilderness of the upper Susquehanna River to the Allegheny River, and the Kuskusky Path, which linked villages throughout the Allegheny Valley. Shawnee, Munsees, Lenape, Susquehannocks, Tuscarora, and Iroquois were among the dozens of tribal groupings that dotted the Pennsylvania frontier on the eve of William Penn's arrival in 1682.

Kuskusky Path, which linked villages throughout the Allegheny Valley. Shawnee, Munsees, Lenape, Susquehannocks, Tuscarora, and Iroquois were among the dozens of tribal groupings that dotted the Pennsylvania frontier on the eve of William Penn's arrival in 1682.

Within a generation's time, a great European migration to Pennsylvania was underway, with a culturally diverse population of immigrants moving through the port of Philadelphia and pushing westward through the Allegheny Mountains. The early Swedish ,

Swedish ,  Finnish, and Dutch settlements, established before Penn's arrival, were overshadowed quickly by the tens of thousands of English, German, Scots-Irish, Welsh, and others who were attracted to Pennsylvania's fertile land and abundant natural resources, and by Penn's

Finnish, and Dutch settlements, established before Penn's arrival, were overshadowed quickly by the tens of thousands of English, German, Scots-Irish, Welsh, and others who were attracted to Pennsylvania's fertile land and abundant natural resources, and by Penn's  promise of religious freedom. Among these were colony's first Anabaptist Mennonites, who in 1710 settled on a 10,000 acre tract near Pequea in present-day Lancaster County on lands deeded by William Penn. Equally noteworthy, a small free black community emerged amidst the growing number of African slaves, estimated in 1750 to represent 6 percent of the total population.

promise of religious freedom. Among these were colony's first Anabaptist Mennonites, who in 1710 settled on a 10,000 acre tract near Pequea in present-day Lancaster County on lands deeded by William Penn. Equally noteworthy, a small free black community emerged amidst the growing number of African slaves, estimated in 1750 to represent 6 percent of the total population.

In 1760, Pennsylvania had an estimated 183,000 inhabitants, only 10 percent of whom lived in Philadelphia. Already, a patchwork quilt of social identities characterized life in town centers and the outlying districts, and denominational diversity complemented the growing ethnic complexity. A multiplicity of languages, creeds, and social institutions supported a varied social world that was officially British but unofficially quite pluralistic. At least in part due to Penn himself and the system of government he installed, a Quaker aristocracy controlled politics and commerce while sharing a sense of "English-ness" with members of the established Church of England (Anglican). A first generation of Welsh Anglicans populated the Welsh Tract outside of Philadelphia, establishing communities and church congregations in places like St. David in Radnor Township.

St. David in Radnor Township.

Himself no stranger to the rough and tumble of cultural politics in eighteenth-century Pennsylvania, Benjamin Franklin worried that non-English settlers would turn Pennsylvania into a "Colony of Aliens." In the 1740s, Franklin expressed deep misgivings about the swarms of "Palatine Boors" who would "Germanize us instead of

Benjamin Franklin worried that non-English settlers would turn Pennsylvania into a "Colony of Aliens." In the 1740s, Franklin expressed deep misgivings about the swarms of "Palatine Boors" who would "Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them," and the anti-authoritarian nature of "zealous Presbyterians" causing trouble on the Pennsylvania frontier. Such characterizations did not endear Franklin to these wary newcomers. Less than two decades later, however, Franklin published an open letter telling prospective immigrants about the opportunities they would find by

our Anglifying them," and the anti-authoritarian nature of "zealous Presbyterians" causing trouble on the Pennsylvania frontier. Such characterizations did not endear Franklin to these wary newcomers. Less than two decades later, however, Franklin published an open letter telling prospective immigrants about the opportunities they would find by moving to America.

moving to America.

William Penn traveled extensively in Germany to attract newcomers to his colony, many of whom were split from their families and sold into long years of servitude to pay for their passage. By the early 1770s, Germans represented about one-third of Pennsylvania's total population. Although some 90 percent of Pennsylvania's German-speaking population was Lutheran or Reformed, it contained its own diversity and strong internal divisions.

to pay for their passage. By the early 1770s, Germans represented about one-third of Pennsylvania's total population. Although some 90 percent of Pennsylvania's German-speaking population was Lutheran or Reformed, it contained its own diversity and strong internal divisions.

A broad array of religious separatists, many of them pacifists like their Quaker neighbors, included Schwenkfelders, Dunkers, Mennonites, Amish , German Quakers, and the Seventh Day Baptists who joined Conrad Beissel at his

Amish , German Quakers, and the Seventh Day Baptists who joined Conrad Beissel at his Ephrata Cloister. Socially and culturally conservative in their habits and beliefs, Mennonite and Amish farming communities dotted the rural landscape of Lancaster, York, Berks, and Lebanon Counties. Like other Germans, these misnamed "Pennsylvania Dutch" held on to their native language and culture, and their chosen detachment from mainstream society.

Ephrata Cloister. Socially and culturally conservative in their habits and beliefs, Mennonite and Amish farming communities dotted the rural landscape of Lancaster, York, Berks, and Lebanon Counties. Like other Germans, these misnamed "Pennsylvania Dutch" held on to their native language and culture, and their chosen detachment from mainstream society.

In the 1740s, a sizable Moravian (Brethren) community from Germany and Bohemia settled in Bethlehem, Nazareth,

Nazareth,  Emmaus, and

Emmaus, and  Lititz, where they built faith-based communities that excluded outsiders. Moravians enjoyed a liturgy filled with song and music, played in many churches on organs built by

Lititz, where they built faith-based communities that excluded outsiders. Moravians enjoyed a liturgy filled with song and music, played in many churches on organs built by  David Tannenberg. In the Oley Valley, German farmers welcomed a small settlement of

David Tannenberg. In the Oley Valley, German farmers welcomed a small settlement of French Huguenots, some of whom were descendants of German-speaking Calvinists.

French Huguenots, some of whom were descendants of German-speaking Calvinists.

Encouraged by land agents like John Logan, Ulster Scots swarmed the frontier in the 1740s and 1750s, spreading across the Susquehanna River and up into the Allegheny highlands. (By 1770 they represented about one-quarter of the Pennsylvania's population.) Presbyterians by conviction and anti-authoritarian in their politics, these Scots-Irish spread their Calvinist faith even as they seized Indian lands and asserted local autonomy from the colonial government in Philadelphia. Well-educated Presbyterian clerics like

spread their Calvinist faith even as they seized Indian lands and asserted local autonomy from the colonial government in Philadelphia. Well-educated Presbyterian clerics like William Tennent and

William Tennent and John McMillan established schools and churches across the expanding wilderness.

John McMillan established schools and churches across the expanding wilderness.

William Penn's dream of peaceful Indian-white relations ended during the French and Indian War, as Ulster Scots, some of whom served in frontier militias, engaged Indians in brutal frontier warfare, with atrocities on both sides. The Paxton Boys' murderous rampage at Conestoga Indiantown in 1763, after which they marched on Philadelphia to overthrow the Quaker-led provincial government, provided an alarming demonstration of the Scots-Irish' growing militancy and political will.

Conestoga Indiantown in 1763, after which they marched on Philadelphia to overthrow the Quaker-led provincial government, provided an alarming demonstration of the Scots-Irish' growing militancy and political will.

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the provincial government's refusal to provide for defense against Indians on the frontier drove may Scots-Irish to the Revolutionary cause. Once war broke out, Pennsylvania's German and Scots-Irish residents rallied to the struggle for independence.

the Revolutionary cause. Once war broke out, Pennsylvania's German and Scots-Irish residents rallied to the struggle for independence.  Thompson's Rifle Battalion, the first officially mustered soldiers in the Continental Army, was largely made up of Scots-Irish and Germans from the Commonwealth's backcountry settlements.

Thompson's Rifle Battalion, the first officially mustered soldiers in the Continental Army, was largely made up of Scots-Irish and Germans from the Commonwealth's backcountry settlements.

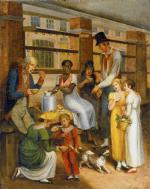

As the successful war for independence from British rule brought Pennsylvania into greater political prominence, many saw the seedbed of national identity in the new Commonwealth's cultural diversity. Philadelphia, the nation's largest, most cosmopolitan, and most multicultural city, became the first capital of the new United States. Leaders of the city's small but thriving African-American population banded together to form the Free African Society for mutual aid, and

Free African Society for mutual aid, and Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church the beginnings of the nation's first independent African-American religious denomination. In the 1790s, Philadelphia experienced a surge in black migration from Haiti and the Caribbean islands, as well as a continuous stream of African-American newcomers from the American South.

Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church the beginnings of the nation's first independent African-American religious denomination. In the 1790s, Philadelphia experienced a surge in black migration from Haiti and the Caribbean islands, as well as a continuous stream of African-American newcomers from the American South.

Mirroring its capital city, Pennsylvania had the greatest ethnic diversity of any state in the new nation. Indeed, it was the only state in the Union in which free whites of English and Welsh descent were a minority. When the first federal census was taken in 1790, Pennsylvania was the second most populous state in the nation. (Virginia, the largest, had 747,610 residents). Of the state's 421,985 residents, the census recorded 38 percent as German, 30 percent as English and Welsh, 15 percent as Scots-Irish, 7 percent as African American-including 10,274 slaves-and 1 percent each as Dutch, French, and Swedish.

Long before Penn and other Europeans imagined Pennsylvania as a haven, a vast North American migration brought hundreds of thousands of American Indians into the Mid-Atlantic region. Not much is known of Pennsylvania's earliest migrants, but simple tools, pieces of pottery, and other evidence of human habitation dating back 14,000 years or more have been found at

By the eighteenth century, a network of overland pathways linked great Indian villages with smaller settlements throughout Pennsylvania's mountains and valleys. These included the

Within a generation's time, a great European migration to Pennsylvania was underway, with a culturally diverse population of immigrants moving through the port of Philadelphia and pushing westward through the Allegheny Mountains. The early

In 1760, Pennsylvania had an estimated 183,000 inhabitants, only 10 percent of whom lived in Philadelphia. Already, a patchwork quilt of social identities characterized life in town centers and the outlying districts, and denominational diversity complemented the growing ethnic complexity. A multiplicity of languages, creeds, and social institutions supported a varied social world that was officially British but unofficially quite pluralistic. At least in part due to Penn himself and the system of government he installed, a Quaker aristocracy controlled politics and commerce while sharing a sense of "English-ness" with members of the established Church of England (Anglican). A first generation of Welsh Anglicans populated the Welsh Tract outside of Philadelphia, establishing communities and church congregations in places like

Himself no stranger to the rough and tumble of cultural politics in eighteenth-century Pennsylvania,

William Penn traveled extensively in Germany to attract newcomers to his colony, many of whom were split from their families and sold into long years of servitude

A broad array of religious separatists, many of them pacifists like their Quaker neighbors, included Schwenkfelders, Dunkers, Mennonites,

In the 1740s, a sizable Moravian (Brethren) community from Germany and Bohemia settled in Bethlehem,

Encouraged by land agents like John Logan, Ulster Scots swarmed the frontier in the 1740s and 1750s, spreading across the Susquehanna River and up into the Allegheny highlands. (By 1770 they represented about one-quarter of the Pennsylvania's population.) Presbyterians by conviction and anti-authoritarian in their politics, these Scots-Irish

William Penn's dream of peaceful Indian-white relations ended during the French and Indian War, as Ulster Scots, some of whom served in frontier militias, engaged Indians in brutal frontier warfare, with atrocities on both sides. The Paxton Boys' murderous rampage at

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the provincial government's refusal to provide for defense against Indians on the frontier drove may Scots-Irish to

As the successful war for independence from British rule brought Pennsylvania into greater political prominence, many saw the seedbed of national identity in the new Commonwealth's cultural diversity. Philadelphia, the nation's largest, most cosmopolitan, and most multicultural city, became the first capital of the new United States. Leaders of the city's small but thriving African-American population banded together to form the

Mirroring its capital city, Pennsylvania had the greatest ethnic diversity of any state in the new nation. Indeed, it was the only state in the Union in which free whites of English and Welsh descent were a minority. When the first federal census was taken in 1790, Pennsylvania was the second most populous state in the nation. (Virginia, the largest, had 747,610 residents). Of the state's 421,985 residents, the census recorded 38 percent as German, 30 percent as English and Welsh, 15 percent as Scots-Irish, 7 percent as African American-including 10,274 slaves-and 1 percent each as Dutch, French, and Swedish.