Chapter 1: From Craft to Industry

The fact that Europeans could construct ships that could navigate across three thousand miles of ocean to the Americas was in itself an indication of their technological sophistication. The construction of a sailing ship required the skills of numerous craftsmen who worked with wood, metal, fiber, and other materials. In the colonial era, technological know-how resided in these skilled craftsmen, who had learned their trade through a long period as apprentices and journeymen before achieving master status. In the late seventeenth century as colonists settled in Pennsylvania, they brought with them technological skills that would be needed to exploit the resources of the region.

Although most settlers became farmers, they still relied on craftsmen, such as blacksmiths, to make or repair iron tools. As farmers started to grow substantial quantities of European wheat and Native-American corn, they needed water-powered grist mills to produce flour and meal. Millwrights employed a variety of skills, including dam and mill race construction, to build what were large machines made primarily of wood. Flowing water turned a waterwheel that, through a series of gears, powered large rotating stones that ground the grain. Although the colonial mill was a European import, American colonists quickly applied water power to sawmills.

colonial mill was a European import, American colonists quickly applied water power to sawmills.

In Pennsylvania where there was great demand for lumber, an abundance of trees, and a shortage of labor, sawmills followed the path of settlement. Lumber became a major Pennsylvania industry. Thus, the saw mill was an early example of the adaptation of European technology to American conditions. To cut down the trees colonists developed a lighter and more efficient axe than the ones they originally brought from Europe.

Two other important adaptations of European technologies were the Pennsylvania rifle and the

Pennsylvania rifle and the  Conestoga wagon, both the products of German craftsmen in Lancaster County. It is impossible to determine a specific date or inventor for these technologies; rather, their designs evolved gradually within a community of craftsmen who borrowed from each other. At some point, however, a more or less standard design did emerge. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Pennsylvania rifle had become a relatively light and long-barreled gun that was accurate at several hundred yards. It became the preferred weapon for hunting and self defense, especially among settlers moving over the Appalachian Mountains. It was so popular on the frontier that it became known as the Kentucky Rifle. Also in the mid-eighteenth century the Conestoga wagon appeared as a general purpose freight vehicle. It was designed to carry goods over the rather poor colonial roads.

Conestoga wagon, both the products of German craftsmen in Lancaster County. It is impossible to determine a specific date or inventor for these technologies; rather, their designs evolved gradually within a community of craftsmen who borrowed from each other. At some point, however, a more or less standard design did emerge. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Pennsylvania rifle had become a relatively light and long-barreled gun that was accurate at several hundred yards. It became the preferred weapon for hunting and self defense, especially among settlers moving over the Appalachian Mountains. It was so popular on the frontier that it became known as the Kentucky Rifle. Also in the mid-eighteenth century the Conestoga wagon appeared as a general purpose freight vehicle. It was designed to carry goods over the rather poor colonial roads.

Lancaster County teamsters began to make regular trips to Philadelphia with food for the inhabitants of the growing urban area. On their return trips they hauled imported or manufactured goods into the hinterland. Other teamsters served the settlers farther out on the frontier in western Pennsylvania. Conestoga wagons carrying supplies served in the British military expeditions to capture the French Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh), during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Although the Conestoga wagon would eventually be replaced by other forms of land transportation, the manufacture of wooden vehicles became a major industry in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century.

Other European craft technologies served as the basis for Pennsylvania industries. One of the first enterprises in early Philadelphia was a tannery. Tanning, which involved soaking hides in noisome substances, created so much air and water pollution that

Tanning, which involved soaking hides in noisome substances, created so much air and water pollution that  Benjamin Franklin tried to get tanneries banned from the city. In spite of such drawbacks, tanning proliferated; there was one tannery for every three grist and

Benjamin Franklin tried to get tanneries banned from the city. In spite of such drawbacks, tanning proliferated; there was one tannery for every three grist and  lumber mills in Pennsylvania. The state's industry peaked around 1900, when Pennsylvania produced more than a quarter of the nation's leather. At this time hemlock trees, being logged extensively in the northern tier counties, such as Tioga County, of the state, provided bark used for tanning.

lumber mills in Pennsylvania. The state's industry peaked around 1900, when Pennsylvania produced more than a quarter of the nation's leather. At this time hemlock trees, being logged extensively in the northern tier counties, such as Tioga County, of the state, provided bark used for tanning.

Paper, then made from linen rags, was an important commodity for books, newspapers, and legal documents. It was a tax on legal documents, the infamous Stamp Act, that particularly infuriated Americans in 1765. The first paper mill in the colonies was constructed about 1690 near Philadelphia–in what became known as Rittenhouse Town – by a Dutch paper maker, William Rittenhouse. His son Claus would operate the paper mill until his death in 1734. The eighteenth century saw the establishment of many other paper mills in Pennsylvania and other colonies.

Rittenhouse Town – by a Dutch paper maker, William Rittenhouse. His son Claus would operate the paper mill until his death in 1734. The eighteenth century saw the establishment of many other paper mills in Pennsylvania and other colonies.

Another important craft was glassblowing. In the 1760s Henry Stiegel established the Stiegel Glass Manufactory that employed European artisans to make fine glassware, which is still valued by collectors today. In the nineteenth century cheap natural gas would fuel a major glass industry along the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania.

Stiegel Glass Manufactory that employed European artisans to make fine glassware, which is still valued by collectors today. In the nineteenth century cheap natural gas would fuel a major glass industry along the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania.

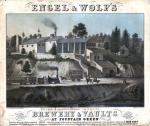

The ancient craft of brewing beer also became well established in America. In the 1840s, a German immigrant to Philadelphia, John Wagner, began to brew America's first lager, which soon became the most popular beer among Americans. Philadelphia and Pennsylvania became major brewing centers for over a century.

America's first lager, which soon became the most popular beer among Americans. Philadelphia and Pennsylvania became major brewing centers for over a century.

These are just some examples of European craft-based technologies that became significant industries in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century. During this period industrialization usually meant centralized production in factories that increasingly used machines driven by water or steam power. Even when machines were not used, factory production entailed extensive division of labor that allowed employment of unskilled workers. The coming of factories, however, did not displace all skilled craftsmen. As machinery proliferated so did jobs for the skilled craftsmen who could make and fix them.

Although most settlers became farmers, they still relied on craftsmen, such as blacksmiths, to make or repair iron tools. As farmers started to grow substantial quantities of European wheat and Native-American corn, they needed water-powered grist mills to produce flour and meal. Millwrights employed a variety of skills, including dam and mill race construction, to build what were large machines made primarily of wood. Flowing water turned a waterwheel that, through a series of gears, powered large rotating stones that ground the grain. Although the

In Pennsylvania where there was great demand for lumber, an abundance of trees, and a shortage of labor, sawmills followed the path of settlement. Lumber became a major Pennsylvania industry. Thus, the saw mill was an early example of the adaptation of European technology to American conditions. To cut down the trees colonists developed a lighter and more efficient axe than the ones they originally brought from Europe.

Two other important adaptations of European technologies were the

Lancaster County teamsters began to make regular trips to Philadelphia with food for the inhabitants of the growing urban area. On their return trips they hauled imported or manufactured goods into the hinterland. Other teamsters served the settlers farther out on the frontier in western Pennsylvania. Conestoga wagons carrying supplies served in the British military expeditions to capture the French Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh), during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Although the Conestoga wagon would eventually be replaced by other forms of land transportation, the manufacture of wooden vehicles became a major industry in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century.

Other European craft technologies served as the basis for Pennsylvania industries. One of the first enterprises in early Philadelphia was a tannery.

Paper, then made from linen rags, was an important commodity for books, newspapers, and legal documents. It was a tax on legal documents, the infamous Stamp Act, that particularly infuriated Americans in 1765. The first paper mill in the colonies was constructed about 1690 near Philadelphia–in what became known as

Another important craft was glassblowing. In the 1760s Henry Stiegel established the

The ancient craft of brewing beer also became well established in America. In the 1840s, a German immigrant to Philadelphia, John Wagner, began to brew

These are just some examples of European craft-based technologies that became significant industries in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century. During this period industrialization usually meant centralized production in factories that increasingly used machines driven by water or steam power. Even when machines were not used, factory production entailed extensive division of labor that allowed employment of unskilled workers. The coming of factories, however, did not displace all skilled craftsmen. As machinery proliferated so did jobs for the skilled craftsmen who could make and fix them.