![header=[Marker Text] body=[The stone gristmill at this site was built in 1704 by Nathaniel Newlin, a Quaker who emigrated from Ireland in 1683. The mill, restored to working order, is a fine example of a vital segment of Colonial economic life.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-322-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0l2n4-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Colonial Gristmill [Industries]

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Delaware

Marker Location:

U.S. 1, 1 mile E of Concordville

Behind the Marker

Colonial farmers rejoiced whenever they learned of the availability of a water-powered gristmill, even if it was twenty or more miles away. The work of hauling their wheat or corn to the mill and back was considered preferable to laboriously grinding one's own grain. Since the Medieval era, mills had dotted the European countryside. When William the Conqueror conducted a census of Britain in 1086, he counted over five thousand water mills, one for every fifty households. A similar concentration of mills existed in America until the widespread application of steam power after the Civil War. In an age when technology resided in the hands of skilled craftsmen, the millwright was a valued member of any community.

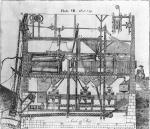

To understand the complexities of gristmill construction, one has to look no further than to The Young Mill-wright and Miller's Guide, written in Philadelphia by inventor Oliver Evans in 1795. This detailed guidebook for mill construction and operation was continuously in print until 1860. (In 1785 Evans had invented a totally automated flour mill that was widely adopted by American millers.) To get power from a stream, the millwright had to construct a dam and mill race to supply water to the waterwheel, which was typically six to thirty feet in diameter.

The Young Mill-wright and Miller's Guide, written in Philadelphia by inventor Oliver Evans in 1795. This detailed guidebook for mill construction and operation was continuously in print until 1860. (In 1785 Evans had invented a totally automated flour mill that was widely adopted by American millers.) To get power from a stream, the millwright had to construct a dam and mill race to supply water to the waterwheel, which was typically six to thirty feet in diameter.

In the colonial era, the average water wheel generated only a few horsepower, but that was adequate to grind grain. Although constructed largely of wood and stone, a gristmill was a true machine, it converted energy to work-and a sophisticated one at that. Usually, a horizontal axle water wheel was turned by the falling water. A series of gears then changed the direction and speed of rotation to a vertical spindle connected to the grinding stone. Other powered operations in a mill often included raking the milled flour to cool it, and bolting or sifting the flour to separate it by particle size. The finest flour was considered to be the best and was often exported to the sugar-growing islands of the West Indies.

In the 1770s about one-third of the wheat grown in southeastern Pennsylvania was being exported. At the same time about forty percent was available for sale locally. Farmers had moved very rapidly from subsistence to commercial agriculture. As the region developed agriculturally, the number of gristmills increased; for example in Chester County they went from 72 in 1759 to 127 in 1781. By 1790 it was estimated that there were over 2,000 gristmills in the new nation. Fifty years later the number of gristmills and sawmills reached 55,000.

By that time the old-fashioned waterwheels were beginning to be replaced by recently developed water turbines that operated at very high efficiencies. As the center of American wheat growing moved westward, the rural water mill went into a long gradual decline, but many continued to operate in the twentieth century. For example, the Mill at Anselma in Chester County operated continuously from the late 1740s until 1932, as did Cumberland County's

Mill at Anselma in Chester County operated continuously from the late 1740s until 1932, as did Cumberland County's  Laughlin Mill from 1763 to 1896. Today, many handsome stone mill buildings survive and can still be seen along the numerous fast falling streams of Pennsylvania.

Laughlin Mill from 1763 to 1896. Today, many handsome stone mill buildings survive and can still be seen along the numerous fast falling streams of Pennsylvania.

To understand the complexities of gristmill construction, one has to look no further than to

In the colonial era, the average water wheel generated only a few horsepower, but that was adequate to grind grain. Although constructed largely of wood and stone, a gristmill was a true machine, it converted energy to work-and a sophisticated one at that. Usually, a horizontal axle water wheel was turned by the falling water. A series of gears then changed the direction and speed of rotation to a vertical spindle connected to the grinding stone. Other powered operations in a mill often included raking the milled flour to cool it, and bolting or sifting the flour to separate it by particle size. The finest flour was considered to be the best and was often exported to the sugar-growing islands of the West Indies.

In the 1770s about one-third of the wheat grown in southeastern Pennsylvania was being exported. At the same time about forty percent was available for sale locally. Farmers had moved very rapidly from subsistence to commercial agriculture. As the region developed agriculturally, the number of gristmills increased; for example in Chester County they went from 72 in 1759 to 127 in 1781. By 1790 it was estimated that there were over 2,000 gristmills in the new nation. Fifty years later the number of gristmills and sawmills reached 55,000.

By that time the old-fashioned waterwheels were beginning to be replaced by recently developed water turbines that operated at very high efficiencies. As the center of American wheat growing moved westward, the rural water mill went into a long gradual decline, but many continued to operate in the twentieth century. For example, the

Beyond the Marker