Chapter One: The Moravians

After tying him to the stake, the Roman Catholic clerics in Prague gave the popular University Rector one last chance to recant his heresies against the church. "God is my witness," John Hus replied, "that I have never taught or preached that which false witnesses have testified against me.... In the truth of that gospel which hitherto I have written, taught, and preached, I now joyfully die." After the fire was lit Hus sang Kyrie Eleison until the smoke stifled his voice. When the flames had done their work, his ashes and even the soil on which they lay were thrown into the Rhine.

For a decade before his martyrdom in 1415, John Hus (1373-1415) had been the Catholic rector of the University of Prague, one of the largest and most prestigious universities in central Europe. Criticizing the Roman Catholic Church for selling indulgences, Hus had begun to preach the "Gospel of Christ" in the Bohemian tongue rather than Latin, argued that all Christians had not just the right but the duty to read and study the Bible for themselves, and called for a return to the "heart religion" practiced by the primitive Christians. When Hus refused to admit to what he deemed false charges of heresy, the Roman Catholic clerics ordered him burned at the stake. But Hus's movement did not die.

In 1457, a large group gathered 200 miles east of Prague outside the castle of Lititz and organized themselves into the Unitas Fratrum, or United Brethren. Sixty years before Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation that would sweep Europe, these men and women began what would become the longest-lived of all Protestant churches. For the next 250 years the United Brethren suffered wave after wave of imprisonment, torture, exile, and suppression. Small bands survived, however, holding onto Hus's vision of "the faith that works"; that is, the practice of faith through the actions of one's daily life and especially Christian love, non-violence, and simplicity.

The Brethren emerged with renewed vigor in the 1720s when Moravian carpenter Christian David met Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf of Saxony, a rich, highly-educated, practical, and deeply religious aristocrat who as a child had been schooled in the teachings of the German pietists by the two noble women who had raised him. Zinzendorf granted David and other Moravian refugees land upon which they built a town they called Herrnut.

Intent upon cultivating harmony among the more than 300 residents of Herrnut, Zinzendorf in 1727 provided a new order for their lives. Believing that men and women, old and young, had different spiritual needs, he divided them into sex and age-segregated "choirs," each one governed by their own elders. A College of Elders presided over the choirs and made all community decisions; above these elders stood Zinzendorf himself.

The foundations of the new faith laid, and believing that it was their duty to bring their message of salvation to all, Zinzendorf sent Moravian missionaries to save souls in neighboring German states and in 1732, in the Dutch West Indies and Greenland.

Outraged at the reappearance of Moravians in Bohemia, the Lutheran Church, now the established church of the region, pressured the King of Saxony to banish Zinzendorf, and the United Brethren were once again on the move. Exiled from Saxony, Zinzendorf founded congregations in Holland, England, Ireland, and elsewhere in Germany. Other Moravians became part of the "Sea Congregations" that emigrated to the West Indies, South America, South Africa, and North America. Within a decade the Moravians had put in place the most ambitious mission program ever developed by the Protestant world.

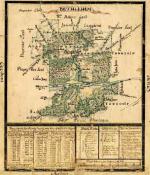

In 1736, Moravians established their first North American colony along the banks of the Savannah River in Georgia. Caught in the war between their British hosts and Spain, the pacifist Brethren moved north to Pennsylvania where they bought 500 acres of land at the confluence of the Monocacy and Lehigh Rivers in northeast Pennsylvania. There on a cold Christmas eve under a sea of stars, the small band of colonists huddled in a single log cabin and held a Moravian "love feast" with the newly arrived Zinzendorf and his daughter. That night Zinzendorf named the new settlement Bethlehem.

Soon afterwards the Brethren purchased 5,000 acres ten miles to the northwest, founding the settlement they named Nazareth. Directed by the General Synod in Germany, the Moravians also founded settlements at

Nazareth. Directed by the General Synod in Germany, the Moravians also founded settlements at  Emmaus in the Lehigh Valley,

Emmaus in the Lehigh Valley,  Lititz in Lancaster County, Hope in northern New Jersey, and

Lititz in Lancaster County, Hope in northern New Jersey, and  Dansbury near the New York border, which served as a base for missionary efforts among the Lenape people.

Dansbury near the New York border, which served as a base for missionary efforts among the Lenape people.

Adopting the communal order under which they had lived at Herrnut, the Moravians at Bethlehem and Nazareth created closed theocratic communities that limited their interaction with outsiders. As they had at Herrnut, they lived in segregated choirs and soon built a separate Brethren's House for single men,

Brethren's House for single men,  Sisters' House for

Sisters' House for  women, and schools for both girls and boys. Organized in 1794,

women, and schools for both girls and boys. Organized in 1794,  Linden Hall in Lititz is the oldest girls' boarding school in the United States.

Linden Hall in Lititz is the oldest girls' boarding school in the United States.

Missionary work remained an essential part of the Moravian order. To keep their focus on a spiritual life while producing the wealth necessary to support their missionary activities, the Moravians at Bethlehem in 1744 voluntarily entered into a "General Economy," whereby they pooled all of their work and resources. The General Economy soon spread to Nazareth, Lititz, and Wachovia, North Carolina - the seat of the Moravians' southern settlements - making it the largest communitarian enterprise in colonial North America.

By 1761, Bethlehem had become a thriving community of more than 2,500 people, close to fifty businesses, and more than 2,000 acres of farmland and pasture.

For Moravians music was an essential aid to worship, so it was part of every religious service and celebration. Moravian choruses won renown for their beautiful harmonies, and Bethlehem became a musical center, its musicians introducing much of the great classical music of Europe to North America. The playing of hymns required the construction of church organs. Between the 1760s and his death in 1804, David Tannenberg built and supervised the installation of nearly fifty instruments of his own design in churches throughout the Commonwealth

David Tannenberg built and supervised the installation of nearly fifty instruments of his own design in churches throughout the Commonwealth

For eighteen years, Nazareth and Bethlehem bore the full financial burden of the Brethren's missionary work in North America. Moravian missionaries worked tirelessly to carry the message of Christ to Europeans and Native Americans in eastern North America. Zinzendorf himself spent two years attempting unsuccessfully to create a grand "Congregation of God in the Spirit" among all the German settlers of Pennsylvania. During his sixty-year career, Moravian missionary David Zeisberger converted hundreds of Lenape and Iroquois.

David Zeisberger converted hundreds of Lenape and Iroquois.

Other colonists often viewed with concern and suspicion the close relations that Moravian missionaries were able to establish with Native American tribes that others feared. After Indian warriors attacked frontier settlements during the bloody French and Indian War of the mid 1700s, a group of vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys in 1763 massacred twenty Conestoga Indian men, women, and children, even though they were pacifist Christians. During the American Revolution, Moravian Indian converts again became victims of war when a band of vigilantes murdered and scalped another ninety-six of them.

Conestoga Indian men, women, and children, even though they were pacifist Christians. During the American Revolution, Moravian Indian converts again became victims of war when a band of vigilantes murdered and scalped another ninety-six of them.

In 1762 the General Synod in Germany ordered the Moravians in Pennsylvania to abandon the General Economy for more traditional family units. At first the change had little impact on the close-knit communities as Moravians continued to live, work, and worship in settlements that excluded outsiders. Gradually, however, many of the faithful moved away from their experiment in utopian Christian community.

As pacifists, Moravians could not bear arms or swear oaths of allegiance during either the French and Indian War or the American Revolution. Bethlehem did, however, serve as a military hospital during the Revolution, and some Moravian men, disobeying orders from the General Synod to shun involvement in political affairs, did supply material support and take up arms for the cause of Independence.

In 1818 the General Synod rejected the Pennsylvania Moravians' petition to bear arms during times of war, but did permit ending the practice of determining marriages by the casting of lots - yes, no, or blank - which Moravians had long practiced as a way to determine God's will.

In accordance with their faith, Moravians emphasized individual conversion to the Gospel of Christ rather than doctrinal conformity. Zinzendorf had begun missionary work to extend the faith not of Moravians - for the Count believed that the Moravians would one day be absorbed by other churches - but of a more ecumenical Protestant Christianity. This, perhaps more than any other single factor, had restrained the growth of the Moravian Church in America.

In the 1820s the General Synod at long last permitted American Moravians to establish new congregations and in 1844 abolished the settlement system that had banned outsiders from moving into Moravian towns. In 1855, American Moravians finally became self-governing when the American provincial synods gathered in Bethlehem and declared their independence from the General Synod.

Deeply committed to their mission to bring Christ's love to non-believers, Moravians continued, in the words of one of their early members, to "fly to every region of America [and the world] as evangelists, as doves from a dove-cote." At the end of the twentieth century the Moravian Church had 39,000 members in the United States and between five hundred and seven hundred thousand worldwide, the largest numbers residing in Tanzania and South Africa.

For a decade before his martyrdom in 1415, John Hus (1373-1415) had been the Catholic rector of the University of Prague, one of the largest and most prestigious universities in central Europe. Criticizing the Roman Catholic Church for selling indulgences, Hus had begun to preach the "Gospel of Christ" in the Bohemian tongue rather than Latin, argued that all Christians had not just the right but the duty to read and study the Bible for themselves, and called for a return to the "heart religion" practiced by the primitive Christians. When Hus refused to admit to what he deemed false charges of heresy, the Roman Catholic clerics ordered him burned at the stake. But Hus's movement did not die.

In 1457, a large group gathered 200 miles east of Prague outside the castle of Lititz and organized themselves into the Unitas Fratrum, or United Brethren. Sixty years before Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation that would sweep Europe, these men and women began what would become the longest-lived of all Protestant churches. For the next 250 years the United Brethren suffered wave after wave of imprisonment, torture, exile, and suppression. Small bands survived, however, holding onto Hus's vision of "the faith that works"; that is, the practice of faith through the actions of one's daily life and especially Christian love, non-violence, and simplicity.

The Brethren emerged with renewed vigor in the 1720s when Moravian carpenter Christian David met Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf of Saxony, a rich, highly-educated, practical, and deeply religious aristocrat who as a child had been schooled in the teachings of the German pietists by the two noble women who had raised him. Zinzendorf granted David and other Moravian refugees land upon which they built a town they called Herrnut.

Intent upon cultivating harmony among the more than 300 residents of Herrnut, Zinzendorf in 1727 provided a new order for their lives. Believing that men and women, old and young, had different spiritual needs, he divided them into sex and age-segregated "choirs," each one governed by their own elders. A College of Elders presided over the choirs and made all community decisions; above these elders stood Zinzendorf himself.

The foundations of the new faith laid, and believing that it was their duty to bring their message of salvation to all, Zinzendorf sent Moravian missionaries to save souls in neighboring German states and in 1732, in the Dutch West Indies and Greenland.

Outraged at the reappearance of Moravians in Bohemia, the Lutheran Church, now the established church of the region, pressured the King of Saxony to banish Zinzendorf, and the United Brethren were once again on the move. Exiled from Saxony, Zinzendorf founded congregations in Holland, England, Ireland, and elsewhere in Germany. Other Moravians became part of the "Sea Congregations" that emigrated to the West Indies, South America, South Africa, and North America. Within a decade the Moravians had put in place the most ambitious mission program ever developed by the Protestant world.

In 1736, Moravians established their first North American colony along the banks of the Savannah River in Georgia. Caught in the war between their British hosts and Spain, the pacifist Brethren moved north to Pennsylvania where they bought 500 acres of land at the confluence of the Monocacy and Lehigh Rivers in northeast Pennsylvania. There on a cold Christmas eve under a sea of stars, the small band of colonists huddled in a single log cabin and held a Moravian "love feast" with the newly arrived Zinzendorf and his daughter. That night Zinzendorf named the new settlement Bethlehem.

Soon afterwards the Brethren purchased 5,000 acres ten miles to the northwest, founding the settlement they named

Adopting the communal order under which they had lived at Herrnut, the Moravians at Bethlehem and Nazareth created closed theocratic communities that limited their interaction with outsiders. As they had at Herrnut, they lived in segregated choirs and soon built a separate

Missionary work remained an essential part of the Moravian order. To keep their focus on a spiritual life while producing the wealth necessary to support their missionary activities, the Moravians at Bethlehem in 1744 voluntarily entered into a "General Economy," whereby they pooled all of their work and resources. The General Economy soon spread to Nazareth, Lititz, and Wachovia, North Carolina - the seat of the Moravians' southern settlements - making it the largest communitarian enterprise in colonial North America.

By 1761, Bethlehem had become a thriving community of more than 2,500 people, close to fifty businesses, and more than 2,000 acres of farmland and pasture.

For Moravians music was an essential aid to worship, so it was part of every religious service and celebration. Moravian choruses won renown for their beautiful harmonies, and Bethlehem became a musical center, its musicians introducing much of the great classical music of Europe to North America. The playing of hymns required the construction of church organs. Between the 1760s and his death in 1804,

For eighteen years, Nazareth and Bethlehem bore the full financial burden of the Brethren's missionary work in North America. Moravian missionaries worked tirelessly to carry the message of Christ to Europeans and Native Americans in eastern North America. Zinzendorf himself spent two years attempting unsuccessfully to create a grand "Congregation of God in the Spirit" among all the German settlers of Pennsylvania. During his sixty-year career, Moravian missionary

Other colonists often viewed with concern and suspicion the close relations that Moravian missionaries were able to establish with Native American tribes that others feared. After Indian warriors attacked frontier settlements during the bloody French and Indian War of the mid 1700s, a group of vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys in 1763 massacred twenty

In 1762 the General Synod in Germany ordered the Moravians in Pennsylvania to abandon the General Economy for more traditional family units. At first the change had little impact on the close-knit communities as Moravians continued to live, work, and worship in settlements that excluded outsiders. Gradually, however, many of the faithful moved away from their experiment in utopian Christian community.

As pacifists, Moravians could not bear arms or swear oaths of allegiance during either the French and Indian War or the American Revolution. Bethlehem did, however, serve as a military hospital during the Revolution, and some Moravian men, disobeying orders from the General Synod to shun involvement in political affairs, did supply material support and take up arms for the cause of Independence.

In 1818 the General Synod rejected the Pennsylvania Moravians' petition to bear arms during times of war, but did permit ending the practice of determining marriages by the casting of lots - yes, no, or blank - which Moravians had long practiced as a way to determine God's will.

In accordance with their faith, Moravians emphasized individual conversion to the Gospel of Christ rather than doctrinal conformity. Zinzendorf had begun missionary work to extend the faith not of Moravians - for the Count believed that the Moravians would one day be absorbed by other churches - but of a more ecumenical Protestant Christianity. This, perhaps more than any other single factor, had restrained the growth of the Moravian Church in America.

In the 1820s the General Synod at long last permitted American Moravians to establish new congregations and in 1844 abolished the settlement system that had banned outsiders from moving into Moravian towns. In 1855, American Moravians finally became self-governing when the American provincial synods gathered in Bethlehem and declared their independence from the General Synod.

Deeply committed to their mission to bring Christ's love to non-believers, Moravians continued, in the words of one of their early members, to "fly to every region of America [and the world] as evangelists, as doves from a dove-cote." At the end of the twentieth century the Moravian Church had 39,000 members in the United States and between five hundred and seven hundred thousand worldwide, the largest numbers residing in Tanzania and South Africa.