Chapter Four: Legacy of Toleration and Reform

A wealthy admiral in the Royal Navy, Sir William Penn enjoyed great favor at the Royal Court for having brought King Charles II back from exile in France. Penn's son, William, however, would repeatedly test his father's and the King's patience. In his mid-twenties, William joined ranks with the Society of Friends, a group of radical religious dissidents who flouted English law and courted conflict. Schooled at Lincoln's Inn, one of England's most prestigious law schools, the fiery youth wrote pamphlets proclaiming that the English courts had no right to arrest Friends exercising their rights to worship and to speak publicly on religious matters.

Jailed in Newgate prison in 1670 for violating a law that prohibited Quaker worship, Penn convinced a jury to acquit him of any wrongdoing in his religious practices. Angry at their decision, the judge imprisoned the jurors for two months. Remaining steadfast, they regained their freedom, after paying fines, and won for all English juries the right to make decisions without fear of reprisals.

A decade after Admiral Penn died in 1670, King Charles II settled the debt he owed him by awarding William Penn 45,000 square miles of forest in North America. Weary of continued persecution, Penn led a small group of Quakers to his new "plantation" in 1682. Upon reaching shore, the fierce defender of conscience assured his followers that this new land would, indeed, be a place of religious toleration.

Penn envisioned his colony as a "Holy Experiment," and introduced a surprising number of reforms and liberties that were then unknown in the Old World. Establishing the colonial government upon laws that limited the power of those in government, Penn permitted Quaker settlers to elect their own representatives. In his First Frame of Government, he also proclaimed his respect for private property, free enterprise, free press, trial by jury, and religious toleration.

Penn and his successors honored those principles and allowed people of differing beliefs to worship in peace. Living by Penn's principles, Aaron Levy in 1789 deeded the town he had founded in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania to local German Protestants and donated a pewter communion set to their church. Five years after the end of the Second World War, 40,000 people would gather in the small Pennsylvania town of Aaronsburg to commemorate the tradition of religious toleration and peaceful coexistence so different from the religious hatred that had recently resulted in the deaths of more than six million European Jews during the Holocaust.

Aaronsburg to commemorate the tradition of religious toleration and peaceful coexistence so different from the religious hatred that had recently resulted in the deaths of more than six million European Jews during the Holocaust.

Although colonial Pennsylvania was a place where people could worship freely, it was not a place where freedom reigned. Slavery was part of everyday life in the colony. In fact, William Penn owned at least three African-American slaves, who worked at his estate, Pennsbury. Many other settlers also owned slaves and participated in the slave trade. By the 1760s more than 4,000 enslaved Africans and African-Americans lived in Pennsylvania, most of them in and around Philadelphia, where they worked as domestic servants, in iron foundries, and for wealthy craftsmen. Traders held slave auctions in front of the

Pennsbury. Many other settlers also owned slaves and participated in the slave trade. By the 1760s more than 4,000 enslaved Africans and African-Americans lived in Pennsylvania, most of them in and around Philadelphia, where they worked as domestic servants, in iron foundries, and for wealthy craftsmen. Traders held slave auctions in front of the  London Coffee House, the major center of business, located just five blocks from the colony's State House – a building soon to become known as Independence Hall.

London Coffee House, the major center of business, located just five blocks from the colony's State House – a building soon to become known as Independence Hall.

The movement to abolish slavery in North America also began in Pennsylvania. Only four years after the first slaves had arrived in Pennsylvania in 1684, German and Dutch Quakers living in Germantown issued the first colonial protest against the owning of other human beings. While the Germantown Protest had little impact at first, by the 1740s Quakers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania were mounting a crusade that would culminate in the abolition of slavery north of the

Germantown Protest had little impact at first, by the 1740s Quakers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania were mounting a crusade that would culminate in the abolition of slavery north of the  Mason-Dixon Line in the decades following the American Revolution.

Mason-Dixon Line in the decades following the American Revolution.

During the Revolution, Philadelphia was a hotbed of abolitionist thought and activity and in 1779, Pennsylvania became the first state in the new nation to pass a law for the emancipation of enslaved Africans and African-Americans. In 1790, Philadelphians organized the Pennsylvania Abolition Society to press for the end of slavery throughout the United States. In the decades preceding the outbreak of the Civil War, African-Americans, Quakers, and other Pennsylvanians would play prominent roles in the crusade for the abolition of slavery throughout the United States, and after the Civil War in the struggle for racial equality. Underground Railroad

Pennsylvania Abolition Society to press for the end of slavery throughout the United States. In the decades preceding the outbreak of the Civil War, African-Americans, Quakers, and other Pennsylvanians would play prominent roles in the crusade for the abolition of slavery throughout the United States, and after the Civil War in the struggle for racial equality. Underground Railroad

Penn remained truer to his Quaker principles in his dealings with Native Americans than he did with Africans. Believing that all men should be treated with dignity, his fair-handed dealings with the Lenape and Native Americans in neighboring territories cemented decades of peace for Pennsylvanians. Benjamin West's famous painting of Penn's treaty with the Lenape, while containing historical inaccuracies, conveyed the sense of trust that existed between the Quakers and their new neighbors.

Quakers were pacifists, who opposed war and violence. Determined to interact honestly and with goodwill towards Native Americans, Penn, albeit misguided at times, established a tradition of respect for humanity of Native Americans that would continue long after his death in 1718. In the last half of the eighteenth century, a number of Indian tribes requested that Quakers act as their advisors at treaty negotiations. In the 1790s the Oneida and Seneca requested that the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting provide them school teachers and instruction in white farming techniques.

The Quaker concern for Native Americans, like their support of the abolition of slavery, had a deep and lasting impact. The Carlisle Indian School, established in 1879 by Richard Pratt and supported by Quaker donations, worked to preserve Indians on the western plains from extinction by teaching them many of the same skills and values that the Quakers had shared with the Oneida and Seneca close to a century before.

Carlisle Indian School, established in 1879 by Richard Pratt and supported by Quaker donations, worked to preserve Indians on the western plains from extinction by teaching them many of the same skills and values that the Quakers had shared with the Oneida and Seneca close to a century before.

Quaker thought, particularly as expressed by a famous Philadelphia Quaker, Dr. Benjamin Rush, also emphasized the humane treatment of criminals. In 1700, Pennsylvania had restricted the death penalty to only two crimes for whites, willful murder and treason, at a time when death was a common punishment for a wide range of crimes throughout the western world. Disturbed by the often-cruel penal systems in the United States, Quakers formulated a new penal code and advanced new ideas for prison organization. Urging the Pennsylvania government to allow them to create a prison system based upon producing penitence and internal reform, the Quakers entered upon their first prison experiment, Eastern State Penitentiary, in 1829.

Eastern State Penitentiary, in 1829.

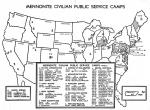

Dedicated to pacifism, the Quaker-dominated government of colonial Pennsylvania resisted the calls of non-Quakers in the colony and the English Crown for military aid and a militia. Their tradition of pacifism, shared by the Amish, Mennonites and Brethren, has continued to the present day. During World War I, Quakers formed the American Friends Service Committee as an alternative to military service for conscientious objectors. With the advent of World War II, the

American Friends Service Committee as an alternative to military service for conscientious objectors. With the advent of World War II, the  Civilian Public Service operated camps where Pennsylvania Quakers, Mennonites, Brethren, and other pacifists could contribute their services to the nation without serving in the military.

Civilian Public Service operated camps where Pennsylvania Quakers, Mennonites, Brethren, and other pacifists could contribute their services to the nation without serving in the military.

Penn's Quaker principles have left a deep and lasting impression on Pennsylvania and the nation. The Quaker respect for the Inner Light of God in all people, regardless of race, gender or class and the emphasis on Brotherhood and nonviolent solutions to conflict informed the national struggle against slavery and racism, the rights of women and Native Americans, the redemption of those convicted of crimes, and other aspects of Penn's Holy Experiment that have been embraced by the United States and the world.

Jailed in Newgate prison in 1670 for violating a law that prohibited Quaker worship, Penn convinced a jury to acquit him of any wrongdoing in his religious practices. Angry at their decision, the judge imprisoned the jurors for two months. Remaining steadfast, they regained their freedom, after paying fines, and won for all English juries the right to make decisions without fear of reprisals.

A decade after Admiral Penn died in 1670, King Charles II settled the debt he owed him by awarding William Penn 45,000 square miles of forest in North America. Weary of continued persecution, Penn led a small group of Quakers to his new "plantation" in 1682. Upon reaching shore, the fierce defender of conscience assured his followers that this new land would, indeed, be a place of religious toleration.

Penn envisioned his colony as a "Holy Experiment," and introduced a surprising number of reforms and liberties that were then unknown in the Old World. Establishing the colonial government upon laws that limited the power of those in government, Penn permitted Quaker settlers to elect their own representatives. In his First Frame of Government, he also proclaimed his respect for private property, free enterprise, free press, trial by jury, and religious toleration.

Penn and his successors honored those principles and allowed people of differing beliefs to worship in peace. Living by Penn's principles, Aaron Levy in 1789 deeded the town he had founded in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania to local German Protestants and donated a pewter communion set to their church. Five years after the end of the Second World War, 40,000 people would gather in the small Pennsylvania town of

Although colonial Pennsylvania was a place where people could worship freely, it was not a place where freedom reigned. Slavery was part of everyday life in the colony. In fact, William Penn owned at least three African-American slaves, who worked at his estate,

The movement to abolish slavery in North America also began in Pennsylvania. Only four years after the first slaves had arrived in Pennsylvania in 1684, German and Dutch Quakers living in Germantown issued the first colonial protest against the owning of other human beings. While the

During the Revolution, Philadelphia was a hotbed of abolitionist thought and activity and in 1779, Pennsylvania became the first state in the new nation to pass a law for the emancipation of enslaved Africans and African-Americans. In 1790, Philadelphians organized the

Penn remained truer to his Quaker principles in his dealings with Native Americans than he did with Africans. Believing that all men should be treated with dignity, his fair-handed dealings with the Lenape and Native Americans in neighboring territories cemented decades of peace for Pennsylvanians. Benjamin West's famous painting of Penn's treaty with the Lenape, while containing historical inaccuracies, conveyed the sense of trust that existed between the Quakers and their new neighbors.

Quakers were pacifists, who opposed war and violence. Determined to interact honestly and with goodwill towards Native Americans, Penn, albeit misguided at times, established a tradition of respect for humanity of Native Americans that would continue long after his death in 1718. In the last half of the eighteenth century, a number of Indian tribes requested that Quakers act as their advisors at treaty negotiations. In the 1790s the Oneida and Seneca requested that the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting provide them school teachers and instruction in white farming techniques.

The Quaker concern for Native Americans, like their support of the abolition of slavery, had a deep and lasting impact. The

Quaker thought, particularly as expressed by a famous Philadelphia Quaker, Dr. Benjamin Rush, also emphasized the humane treatment of criminals. In 1700, Pennsylvania had restricted the death penalty to only two crimes for whites, willful murder and treason, at a time when death was a common punishment for a wide range of crimes throughout the western world. Disturbed by the often-cruel penal systems in the United States, Quakers formulated a new penal code and advanced new ideas for prison organization. Urging the Pennsylvania government to allow them to create a prison system based upon producing penitence and internal reform, the Quakers entered upon their first prison experiment,

Dedicated to pacifism, the Quaker-dominated government of colonial Pennsylvania resisted the calls of non-Quakers in the colony and the English Crown for military aid and a militia. Their tradition of pacifism, shared by the Amish, Mennonites and Brethren, has continued to the present day. During World War I, Quakers formed the

Penn's Quaker principles have left a deep and lasting impression on Pennsylvania and the nation. The Quaker respect for the Inner Light of God in all people, regardless of race, gender or class and the emphasis on Brotherhood and nonviolent solutions to conflict informed the national struggle against slavery and racism, the rights of women and Native Americans, the redemption of those convicted of crimes, and other aspects of Penn's Holy Experiment that have been embraced by the United States and the world.