![header=[Marker Text] body=[Here in 1688, at the home of Tunes Kunders, an eloquent protest was written by a group of German Quakers. Signed by Pastorius and three others, it preceded by 92 years Pennsylvania's passage of the nation's first state abolition law. ] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-F8-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a4f7-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

First Protest Against Slavery

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

5109 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia

Dedication Date:

October 8, 1983

Behind the Marker

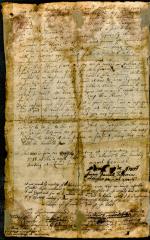

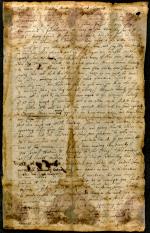

"Germantown Friend's Protest Against Slavery," 1688.

In 1688, only seven years after William Penn received his the charter for his "Holy Experiment" based on religious freedom and tolerance, four German Quakers, none of whom had been in the colony for more than five years, issued the first formal protest against slavery in Pennsylvania; indeed, the first formal protest issued anywhere in Britain's North American colonies. The men who signed it were among the first great wave of German immigrants drawn to the colony by William Penn's direct appeals to religious dissenters in Europe, and like Penn, they believed that the inner light of God was present in all people.

Envisioning a utopian society, Penn included a bill of rights in his 1682 "Frame of Government of Pennsylvania." Despite this framework, Penn, however, failed to ban slavery. Faced with acute labor shortages, some of the English Quakers who settled Pennsylvania, and William Penn himself, purchased and owned enslaved Africans, the first 150 of whom arrived in 1684 to help clear ground for the new colony.

Four years later, Pastorius and a small group of other German settlers met at the Germantown home of cloth dyer Tunes Kunders and there wrote a protest that employed a broad range of arguments both principled and practical. First drawing on the golden rule as they explained it in the quote above, they argued that slavery was un-Christian, that liberty of body was as much a right as liberty of conscience, that it was hypocritical, that it gave the colony a bad name, that the need to suppress a rebellion enslaved people would violate Quaker pacifism, that it gave the Pennsylvania Society of Friends and the colony a bad reputation, and that it would prevent the immigration of the Germans and Dutch who abhorred the practice.

The protest first went to the local Weekly Meeting of the Society of Friends. Deeming it too important-and controversial–an issue for the meeting to address, they sent the protest to the Monthly Meeting at Dublin and then to the Quarterly Meeting at Philadelphia with the same results. In July 1688, the petition reached the Yearly Meeting, which chose not to act on the protest, deciding not to pass judgment or act against slavery.

The issue, however, did not die. The next protest came only five years later, made by an anonymous group of Quakers in 1693. This was followed by other protests-and by the growing number of slaves in the colony; some 4,000 by the mid-1700s. The Quaker crusade against slavery took its next leap forward in the 1750s, when New Jersey Quaker John Woolman published Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes (1754), an extended and impassioned argument against the human slavery.

Pressured by Woolman, Anthony Benezet, and other abolitionists, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1758 condemned the importation, holding, and buying and selling of salves and took steps to remove slaveholders from leadership positions. Slave buyers and sellers now faced disownment by the Yearly Meeting, which called for members to report all those refusing to free their slaves to the next Yearly Meeting. Monthly Meetings then organized committees to visit slave owners in the attempt to obtain manumissions for all slaves.

As the American Revolution approached the contradictions between their own demands for freedom and liberty from English tyranny and the simultaneous enslavement of people of color fueled the founding in 1775, by Anthony Benezet and nine other Quakers of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

The movement for abolition continued to grow, and on March 1, 1780, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed a law calling for the gradual emancipation of slavery. The new law, the first of its kind in the United States, failed to free slaves already held in bondage; the children of slaves remained in indentured servitude until the age of twenty-eight. It did, however, prevent the enslavement of future generations.

law calling for the gradual emancipation of slavery. The new law, the first of its kind in the United States, failed to free slaves already held in bondage; the children of slaves remained in indentured servitude until the age of twenty-eight. It did, however, prevent the enslavement of future generations.

Outlawed by most northern states soon after national independence, slavery expanded in the American South and gave birth to a new abolition movement in which Lucretia Mott, Thomas Garrett, and other Pennsylvania Quakers played important roles. In 1844, Philadelphia Quaker and antiquarian Nathan Kite rediscovered the long forgotten Germantown protest and published it in The Friend: A Religious and Literary Journal.

Germantown protest and published it in The Friend: A Religious and Literary Journal.

Remembrance of the Germantown Protest came to life again when celebrated American poet John Greenleaf Whittier in 1872 made Pastorius the hero of his narrative poem, "The Pennsylvania Pilgrim." A Quaker-born abolitionist, Whittier directly addressed the meaning of Pastorius's long forgotten legacy, ending his poem with the following words:

For, ere Pastorius left the sun and air,

God sent the answer to his life-long prayer;

The child [John Woolman] was born beside the Delaware,

Who, in the power a holy purpose lends,

Guided his people unto nobler ends,

And left them worthier of the name of Friends.

And to! the fulness of the time has come,

And over all the exile's Western home,

From sea to sea the flowers of freedom bloom!

And joy-bells ring, and silver trumpets blow;

But not for thee, Pastorius! Even so

The world forgets, but the wise angels know.

"These are the reasons why we are against the traffik of men-body... Is there any that would be done or handled at this manner? ...There is a saying, that we shall doe to all men, like as we will be done our selves: making no difference of what generation, descent, or colour they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who buy or purchase them, are they not all alike?"  First Protest

First Protest

"Germantown Friend's Protest Against Slavery," 1688.

In 1688, only seven years after William Penn received his the charter for his "Holy Experiment" based on religious freedom and tolerance, four German Quakers, none of whom had been in the colony for more than five years, issued the first formal protest against slavery in Pennsylvania; indeed, the first formal protest issued anywhere in Britain's North American colonies. The men who signed it were among the first great wave of German immigrants drawn to the colony by William Penn's direct appeals to religious dissenters in Europe, and like Penn, they believed that the inner light of God was present in all people.

Envisioning a utopian society, Penn included a bill of rights in his 1682 "Frame of Government of Pennsylvania." Despite this framework, Penn, however, failed to ban slavery. Faced with acute labor shortages, some of the English Quakers who settled Pennsylvania, and William Penn himself, purchased and owned enslaved Africans, the first 150 of whom arrived in 1684 to help clear ground for the new colony.

Four years later, Pastorius and a small group of other German settlers met at the Germantown home of cloth dyer Tunes Kunders and there wrote a protest that employed a broad range of arguments both principled and practical. First drawing on the golden rule as they explained it in the quote above, they argued that slavery was un-Christian, that liberty of body was as much a right as liberty of conscience, that it was hypocritical, that it gave the colony a bad name, that the need to suppress a rebellion enslaved people would violate Quaker pacifism, that it gave the Pennsylvania Society of Friends and the colony a bad reputation, and that it would prevent the immigration of the Germans and Dutch who abhorred the practice.

The protest first went to the local Weekly Meeting of the Society of Friends. Deeming it too important-and controversial–an issue for the meeting to address, they sent the protest to the Monthly Meeting at Dublin and then to the Quarterly Meeting at Philadelphia with the same results. In July 1688, the petition reached the Yearly Meeting, which chose not to act on the protest, deciding not to pass judgment or act against slavery.

The issue, however, did not die. The next protest came only five years later, made by an anonymous group of Quakers in 1693. This was followed by other protests-and by the growing number of slaves in the colony; some 4,000 by the mid-1700s. The Quaker crusade against slavery took its next leap forward in the 1750s, when New Jersey Quaker John Woolman published Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes (1754), an extended and impassioned argument against the human slavery.

Pressured by Woolman, Anthony Benezet, and other abolitionists, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1758 condemned the importation, holding, and buying and selling of salves and took steps to remove slaveholders from leadership positions. Slave buyers and sellers now faced disownment by the Yearly Meeting, which called for members to report all those refusing to free their slaves to the next Yearly Meeting. Monthly Meetings then organized committees to visit slave owners in the attempt to obtain manumissions for all slaves.

As the American Revolution approached the contradictions between their own demands for freedom and liberty from English tyranny and the simultaneous enslavement of people of color fueled the founding in 1775, by Anthony Benezet and nine other Quakers of the

The movement for abolition continued to grow, and on March 1, 1780, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed a

Outlawed by most northern states soon after national independence, slavery expanded in the American South and gave birth to a new abolition movement in which Lucretia Mott, Thomas Garrett, and other Pennsylvania Quakers played important roles. In 1844, Philadelphia Quaker and antiquarian Nathan Kite rediscovered the long forgotten

Remembrance of the Germantown Protest came to life again when celebrated American poet John Greenleaf Whittier in 1872 made Pastorius the hero of his narrative poem, "The Pennsylvania Pilgrim." A Quaker-born abolitionist, Whittier directly addressed the meaning of Pastorius's long forgotten legacy, ending his poem with the following words:

For, ere Pastorius left the sun and air,

God sent the answer to his life-long prayer;

The child [John Woolman] was born beside the Delaware,

Who, in the power a holy purpose lends,

Guided his people unto nobler ends,

And left them worthier of the name of Friends.

And to! the fulness of the time has come,

And over all the exile's Western home,

From sea to sea the flowers of freedom bloom!

And joy-bells ring, and silver trumpets blow;

But not for thee, Pastorius! Even so

The world forgets, but the wise angels know.

Beyond the Marker