Chapter one: The Early Years

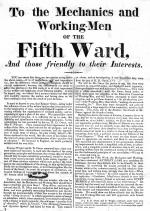

In 1828, Philadelphia's Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations made a stinging observation: the "unequal and very excessive accumulation of wealth and power into the hands of a few" has brought "our condition in society lower than justice

Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations made a stinging observation: the "unequal and very excessive accumulation of wealth and power into the hands of a few" has brought "our condition in society lower than justice demands it should be." To defend against the hunger, poverty, and unemployment that the city's workers had faced for years, and to demand the ten-hour-day, members formed the country's first central labor body to unite skilled craftsmen and day laborers. City employers claimed to be shocked by this new organization, but they should not have been.

demands it should be." To defend against the hunger, poverty, and unemployment that the city's workers had faced for years, and to demand the ten-hour-day, members formed the country's first central labor body to unite skilled craftsmen and day laborers. City employers claimed to be shocked by this new organization, but they should not have been.

Pennsylvania workers had been forming protective associations since 1724, when the Carpenters' Company, the first colonial association of a single craft, demanded safe and secure employment. The carpenters went on strike, and within three years, other city skilled workers organized themselves into unions by trade. In 1794, Philadelphia's shoemakers combined skilled and unskilled workers into the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers. Carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, and printers from small shops across the city followed with several turn-outs during the 1790s.

Labor organizing was less successful outside major cities. One reason for this was that rurally situated iron plantations, such as the Cornwall and

Cornwall and  Hopewell Furnaces, continued to employ itinerant workers and slaves, while the booming overland freight-hauling industry utilized

Hopewell Furnaces, continued to employ itinerant workers and slaves, while the booming overland freight-hauling industry utilized  Conestoga Wagons that employed thousands of waggoners, blacksmiths, and draymen. Grist and saw mills, like

Conestoga Wagons that employed thousands of waggoners, blacksmiths, and draymen. Grist and saw mills, like  Newlin Mill in Glen Mills, divided workers into specialized skills, which made labor organization difficult. Meanwhile, immigrants from Ireland, Scotland, and Germany found work on the western roads and canals, where they protested substandard wages and long hours regularly, but where foreign and itinerant workers also could be replaced easily when they protested.

Newlin Mill in Glen Mills, divided workers into specialized skills, which made labor organization difficult. Meanwhile, immigrants from Ireland, Scotland, and Germany found work on the western roads and canals, where they protested substandard wages and long hours regularly, but where foreign and itinerant workers also could be replaced easily when they protested.

When Philadelphia's Cordwainers turned out again in 1805, eight leaders were charged with conspiring to raise wages without consent from employers and coercing fellow journeymen into supporting their strike. In the famous Commonwealth v. Pullis case (1806), the Mayor's Court of Philadelphia found the strikers guilty and ordered each of them to pay $8 to their employers, a penalty amounting to four times their monthly rent. The courts continued to uphold a "conspiracy" doctrine in law, which stipulated the absolute right of employers to determine the conditions of labor; the courts thus stood firmly behind the "mushroom capitalists" who invested in the new technologies of Pennsylvania's emerging industrial revolution.

"Canal fever," followed by the railroad building boom, brought a sharp decline in transportation costs and great profits for capitalist investors, further bolstering the antiunion position. But the manufacturing revolution also kept wages low, and fueled the ethnic and racial tensions that arose with new immigration from abroad and the freeing of African Americans in the North.

In 1835, the General Trades' Union (GTU) of Philadelphia, made up of a variety of occupational groups, immigrants, and skilled workers, sponsored another strike for a ten-hour day, then paid for the legal defense of workers charged with "conspiracy to raise wages." Massive strikes broke out in 1836 of the Irish handloom weavers in Manayunk and printers organized the Pittsburgh Typographical Union No. 7, today the city's the oldest continually existing labor organization. By then, Philadelphia hosted fifty-eight labor organizations, and Pittsburgh had thirteen. One of these, the Union Beneficial Society of Journeymen Cordwainers, developed a "Ladies Branch" of shoe binders and sewers.

But labor victories were bittersweet in the 1830s. Shop owners with enough capital began to take production out of craftsmen's hands and expand the size of their operations. In the "sweating system," the new owners demanded greater productivity for lower pay. In printing, as in other trades, control passed from skilled professionals into the hands of outsiders, including many "two-thirders," or partially trained journeymen and children. As one mechanic complained, "the capitalists have taken to bossing every ... journeyman [who is] subject to be discharged at every pretended 'miff' of his purse-proud employer."

In their quest for expansion and profits, iron mine and foundry owners ruthlessly cut the wages of skilled molders and embraced piecework performed by poorly trained and poorly paid helpers and apprentices. They forced skilled workers to buy their own tools, purchase food and clothing at company stores, forego compensation for injuries, and accept part of their pay months later as "an assurance of good behavior."

The Panic of 1837, which initiated a prolonged and severe economic downturn, forced Pennsylvanians in all walks of life into conditions of basic survival. As thousands of urban tradesmen and rural iron furnace workers faced unemployment and substandard wages, unions lost membership and many workers withdrew from political reform activities. At the same time, contrasts grew starker between the rising comforts of a "middle class" and the long hours of work and low wages of most Pennsylvanians. A blacksmith, recalling an earlier time when "every worker knew his employer," lamented that now "men and masters became estranged and the gulf could only be healed by a strike."

In 1845, female workers in five cotton factories staged an angry and well-publicized strike for the ten-hour day at the Allegheny Cotton Mills near Pittsburgh. The death of fifty-seven Irishmen working on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad and their unmarked burial at

Allegheny Cotton Mills near Pittsburgh. The death of fifty-seven Irishmen working on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad and their unmarked burial at  Duffy's Cut near Malvern became a reminder of a disregard for human life becoming common in the rush to riches.

Duffy's Cut near Malvern became a reminder of a disregard for human life becoming common in the rush to riches.

Shocked by the exploitation of workers, a reporter for the Atlantic Monthly described ghastly scenes in foundries of "masses of men with dull, besotted faces bent to the ground ... begrimed with smoke and ashes, stooping all night over boiling cauldrons of metal." A newspaperman documenting the anthracite-coal mines wrote of children "stooped over, their backs already forever bent to their heavy buckets of coal." Shamed into action, the Pennsylvania legislature in 1848 passed a law making twelve the minimum age for working, and ten the maximum hours of labor a day, but evasions of both laws were regular.

Following the Civil War, Pennsylvania experienced astounding industrial expansion. The state's population tripled, railroad track grew ten times, and the industrial labor force nearly tripled in less thirty years. Larger factories hired thousands of more recent immigrants from Europe at low wages, workers who helped meet the burgeoning demand for roads and canals, housing, consumer goods, and clothing. At the same time, employers put intense pressure on workers to produce faster, refusing to improve hazardous conditions and firing workers for illness or injury.

Horrific accidents continued occur in Pennsylvania mining country, including the Avondale Mine Disaster of 1869 in Luzerne County, where a devastating fire and oxygen depletion killed 110 miners. Under these conditions, workers unleashed a wave of labor organizing across the Commonwealth. One of the results was the National Labor Union (NLU), formed in 1866 by

Avondale Mine Disaster of 1869 in Luzerne County, where a devastating fire and oxygen depletion killed 110 miners. Under these conditions, workers unleashed a wave of labor organizing across the Commonwealth. One of the results was the National Labor Union (NLU), formed in 1866 by  William H. Sylvis. The NLU promoted the affiliation of craft workers, producers' cooperatives, political activism, and most importantly, the eight-hour day.

William H. Sylvis. The NLU promoted the affiliation of craft workers, producers' cooperatives, political activism, and most importantly, the eight-hour day.

The shorter workday, however, lay in the future, and in anthracite, or "hard coal" mining areas of northeastern Pennsylvania, immigrants experienced grinding poverty. Many miners turned in desperation to the Molly Maguires, which staged periodic sabotage and work stoppages. Their activities spread to the new railroad lines of western Pennsylvania until they were crushed by Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and his armed force of Coal and Iron police.

Molly Maguires, which staged periodic sabotage and work stoppages. Their activities spread to the new railroad lines of western Pennsylvania until they were crushed by Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and his armed force of Coal and Iron police.

The mid-1800s witnessed the rise of farm tenancy and sharecropping, as well. In Cumberland County, for example, nearly 40 percent of all farms were tenant-operated. Pennsylvania farmers responded to new technologies, higher railroad transportation costs, and the price gouging of big business by forming Granges. The first of these, the

Cumberland County, for example, nearly 40 percent of all farms were tenant-operated. Pennsylvania farmers responded to new technologies, higher railroad transportation costs, and the price gouging of big business by forming Granges. The first of these, the  Eagle Grange #1, was organized in Lycoming County in 1871 to pressure the state legislature for laws to protect farm interests.

Eagle Grange #1, was organized in Lycoming County in 1871 to pressure the state legislature for laws to protect farm interests.

Larger and more moderate labor organizations also rose alongside the NLU and Mollies. Pennsylvanians Uriah S. Stephens and Terence V. Powderly both led The Noble Order of the Knights of Labor,

Terence V. Powderly both led The Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, founded in 1869, which united industrial workers and which, for the first time in union history, included female and African-American workers. The program of the Knights, expressed in the motto "an injury to one is the concern of all," demanded the eight-hour day, abolition of child and convict labor, equal pay for equal work, and boycotts of private banks that discriminated against small savers

founded in 1869, which united industrial workers and which, for the first time in union history, included female and African-American workers. The program of the Knights, expressed in the motto "an injury to one is the concern of all," demanded the eight-hour day, abolition of child and convict labor, equal pay for equal work, and boycotts of private banks that discriminated against small savers

Pennsylvania workers had been forming protective associations since 1724, when the Carpenters' Company, the first colonial association of a single craft, demanded safe and secure employment. The carpenters went on strike, and within three years, other city skilled workers organized themselves into unions by trade. In 1794, Philadelphia's shoemakers combined skilled and unskilled workers into the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers. Carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, and printers from small shops across the city followed with several turn-outs during the 1790s.

Labor organizing was less successful outside major cities. One reason for this was that rurally situated iron plantations, such as the

When Philadelphia's Cordwainers turned out again in 1805, eight leaders were charged with conspiring to raise wages without consent from employers and coercing fellow journeymen into supporting their strike. In the famous Commonwealth v. Pullis case (1806), the Mayor's Court of Philadelphia found the strikers guilty and ordered each of them to pay $8 to their employers, a penalty amounting to four times their monthly rent. The courts continued to uphold a "conspiracy" doctrine in law, which stipulated the absolute right of employers to determine the conditions of labor; the courts thus stood firmly behind the "mushroom capitalists" who invested in the new technologies of Pennsylvania's emerging industrial revolution.

"Canal fever," followed by the railroad building boom, brought a sharp decline in transportation costs and great profits for capitalist investors, further bolstering the antiunion position. But the manufacturing revolution also kept wages low, and fueled the ethnic and racial tensions that arose with new immigration from abroad and the freeing of African Americans in the North.

In 1835, the General Trades' Union (GTU) of Philadelphia, made up of a variety of occupational groups, immigrants, and skilled workers, sponsored another strike for a ten-hour day, then paid for the legal defense of workers charged with "conspiracy to raise wages." Massive strikes broke out in 1836 of the Irish handloom weavers in Manayunk and printers organized the Pittsburgh Typographical Union No. 7, today the city's the oldest continually existing labor organization. By then, Philadelphia hosted fifty-eight labor organizations, and Pittsburgh had thirteen. One of these, the Union Beneficial Society of Journeymen Cordwainers, developed a "Ladies Branch" of shoe binders and sewers.

But labor victories were bittersweet in the 1830s. Shop owners with enough capital began to take production out of craftsmen's hands and expand the size of their operations. In the "sweating system," the new owners demanded greater productivity for lower pay. In printing, as in other trades, control passed from skilled professionals into the hands of outsiders, including many "two-thirders," or partially trained journeymen and children. As one mechanic complained, "the capitalists have taken to bossing every ... journeyman [who is] subject to be discharged at every pretended 'miff' of his purse-proud employer."

In their quest for expansion and profits, iron mine and foundry owners ruthlessly cut the wages of skilled molders and embraced piecework performed by poorly trained and poorly paid helpers and apprentices. They forced skilled workers to buy their own tools, purchase food and clothing at company stores, forego compensation for injuries, and accept part of their pay months later as "an assurance of good behavior."

The Panic of 1837, which initiated a prolonged and severe economic downturn, forced Pennsylvanians in all walks of life into conditions of basic survival. As thousands of urban tradesmen and rural iron furnace workers faced unemployment and substandard wages, unions lost membership and many workers withdrew from political reform activities. At the same time, contrasts grew starker between the rising comforts of a "middle class" and the long hours of work and low wages of most Pennsylvanians. A blacksmith, recalling an earlier time when "every worker knew his employer," lamented that now "men and masters became estranged and the gulf could only be healed by a strike."

In 1845, female workers in five cotton factories staged an angry and well-publicized strike for the ten-hour day at the

Shocked by the exploitation of workers, a reporter for the Atlantic Monthly described ghastly scenes in foundries of "masses of men with dull, besotted faces bent to the ground ... begrimed with smoke and ashes, stooping all night over boiling cauldrons of metal." A newspaperman documenting the anthracite-coal mines wrote of children "stooped over, their backs already forever bent to their heavy buckets of coal." Shamed into action, the Pennsylvania legislature in 1848 passed a law making twelve the minimum age for working, and ten the maximum hours of labor a day, but evasions of both laws were regular.

Following the Civil War, Pennsylvania experienced astounding industrial expansion. The state's population tripled, railroad track grew ten times, and the industrial labor force nearly tripled in less thirty years. Larger factories hired thousands of more recent immigrants from Europe at low wages, workers who helped meet the burgeoning demand for roads and canals, housing, consumer goods, and clothing. At the same time, employers put intense pressure on workers to produce faster, refusing to improve hazardous conditions and firing workers for illness or injury.

Horrific accidents continued occur in Pennsylvania mining country, including the

The shorter workday, however, lay in the future, and in anthracite, or "hard coal" mining areas of northeastern Pennsylvania, immigrants experienced grinding poverty. Many miners turned in desperation to the

The mid-1800s witnessed the rise of farm tenancy and sharecropping, as well. In

Larger and more moderate labor organizations also rose alongside the NLU and Mollies. Pennsylvanians Uriah S. Stephens and