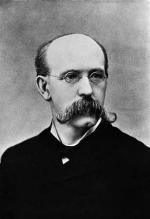

![header=[Marker Text] body=[Noted labor leader. Born Jan. 22, 1849, in Carbondale. Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, 1879-93. Scranton's Mayor, 1878-84. Later Federal immigration official. Died in 1924] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-3BE-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0m8d1-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Terence V. Powderly

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Lackawanna

Marker Location:

N. Main Ave. near Mears St., West Scranton

Dedication Date:

November 18, 1947

Behind the Marker

In 1878, Democrats and Republicans in Scranton, Pennsylvania, joined forces to run a single candidate for mayor against twenty-nine-year-old Terence Powderly, a fiery, outspoken, non-drinking Irish-American who represented the upstart Greenback-Labor Party.

Despite charges that Powderly's victory would bring back the Molly Maguires and a reign of terror against respectable citizens, Powderly beat the fusion candidate by 534 votes. For the next five years he not only served as mayor but also as head of the Knights of Labor, the most powerful labor union in the United States. He managed to wear both hats successfully until he resigned as mayor to devote full-time to labor organizing in 1884.

Molly Maguires and a reign of terror against respectable citizens, Powderly beat the fusion candidate by 534 votes. For the next five years he not only served as mayor but also as head of the Knights of Labor, the most powerful labor union in the United States. He managed to wear both hats successfully until he resigned as mayor to devote full-time to labor organizing in 1884.

Powderly was born in Carbondale, a small town just north of Scranton, in 1849. Trained as a machinist, he moved to Scranton at the age of twenty and worked for the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad. There, in 1872, he began to organize workers for the Machinists' and Blacksmiths' International Union. Fired for his union activities, in 1876 he founded the first Greenback-Labor club in the Scranton area.

At the time, the nation was in the midst of a depression that the Greenback-Labor Party said would end if the government legalized paper currency to increase the money supply and thereby provide consumers with much-needed purchasing power to get industrial production rolling again. It also sought to legalize unions' rights to bargain collectively and to combat political corruption. In 1878, Powderly was elected the mayor of Scranton on the Greenback-Labor ticket.

Powderly and the Greenback-Labor Party succeeded in Scranton because it was a small city with a highly skilled work force, distributed among many companies, and a thriving middle class of shopkeepers who catered to the miners and farmers in the surrounding area. Thus, the Republican machine could not march industrial workers and city public-service employees to the polls to vote the machine ticket or lose their jobs. Reading, too, established its independence from traditional politics by electing Socialist James Maurer, first to the state legislature and then to Congress in the early 1900s.

James Maurer, first to the state legislature and then to Congress in the early 1900s.

Re-elected as mayor in 1880 and 1882, Powderly oversaw the creation of a board of health, a sewage system, street paving, a new police force and fire department, and an investigation of municipal corruption that led to a more efficient system of tax collection. During a smallpox epidemic in 1881-1882, he organized the free vaccination of citizens, holding the number of deaths to twenty-seven. His fiscally honest administration reduced a $350,000 city debt to $20,000 at the same time that it increased the budget paid for city services from $68,000 to $120,000.

In 1879 Powderly became head of the fledgling Knights of Labor, which he built into the nation's largest labor organization. Declining to run for a fourth term as mayor, he devoted his energies after 1884 to the union, which by 1886 boasted a membership of more than a half million.

The Knights had swelled in membership following a successful strike against Jay Gould's Southwestern Railroad, but Powderly strongly opposed strikes and political activity in favor of arbitration and the combination of all workers into one union. He welcomed African-Americans, 60,000 of whom joined the Knights, and women. And he offered workers with a powerful vision of the future, dreaming that "There is no reason why labor cannot, through cooperation, own and operate mines, factories and railroads."

Jay Gould's Southwestern Railroad, but Powderly strongly opposed strikes and political activity in favor of arbitration and the combination of all workers into one union. He welcomed African-Americans, 60,000 of whom joined the Knights, and women. And he offered workers with a powerful vision of the future, dreaming that "There is no reason why labor cannot, through cooperation, own and operate mines, factories and railroads."

In May 1886, the Knights mobilized a nationwide strike for an eight-hour work day - the first organized nationwide strike in American history - an initiative that Powderly did not endorse. When a bomb exploded during a rally in Chicago on May 3, killing eight policemen in the infamous Haymarket Square Riot, the Knights soon lost public support and its hold as employers mounted a determined counteroffensive against Knights job actions.

By the late 1880s, the American Federation of Labor, a breakoff group from the Knights, had emerged as the nation's most effective voice for working people, through organizing skilled workers by trade - largely white, male, native-born workers - and winning higher wages and better working conditions for them (thus ignoring the needs of other laboring people who had been enrolled in the Knights movement).

American Federation of Labor, a breakoff group from the Knights, had emerged as the nation's most effective voice for working people, through organizing skilled workers by trade - largely white, male, native-born workers - and winning higher wages and better working conditions for them (thus ignoring the needs of other laboring people who had been enrolled in the Knights movement).

In 1892, Powderly supported Populist Party candidate James Weaver for president and wrote a brief prediction of what the nation would look like 100 years in the future. Expelled by the Knights of Labor the next year for his support of Weaver, Powderly became a Republican, supported Republican William McKinley in 1896. He was rewarded for his change of allegiance with appointments in the Bureau of Immigration and Department of Labor, in which he worked for much of the remainder of his life.

100 years in the future. Expelled by the Knights of Labor the next year for his support of Weaver, Powderly became a Republican, supported Republican William McKinley in 1896. He was rewarded for his change of allegiance with appointments in the Bureau of Immigration and Department of Labor, in which he worked for much of the remainder of his life.

Powderly spent the last years of his life in Washington, D.C., where he died in 1924. Even in his later years he remained an eloquent defender of the laboring men and women and critic of the American adulation of men of wealth.

critic of the American adulation of men of wealth.

Despite charges that Powderly's victory would bring back the

Powderly was born in Carbondale, a small town just north of Scranton, in 1849. Trained as a machinist, he moved to Scranton at the age of twenty and worked for the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad. There, in 1872, he began to organize workers for the Machinists' and Blacksmiths' International Union. Fired for his union activities, in 1876 he founded the first Greenback-Labor club in the Scranton area.

At the time, the nation was in the midst of a depression that the Greenback-Labor Party said would end if the government legalized paper currency to increase the money supply and thereby provide consumers with much-needed purchasing power to get industrial production rolling again. It also sought to legalize unions' rights to bargain collectively and to combat political corruption. In 1878, Powderly was elected the mayor of Scranton on the Greenback-Labor ticket.

Powderly and the Greenback-Labor Party succeeded in Scranton because it was a small city with a highly skilled work force, distributed among many companies, and a thriving middle class of shopkeepers who catered to the miners and farmers in the surrounding area. Thus, the Republican machine could not march industrial workers and city public-service employees to the polls to vote the machine ticket or lose their jobs. Reading, too, established its independence from traditional politics by electing Socialist

Re-elected as mayor in 1880 and 1882, Powderly oversaw the creation of a board of health, a sewage system, street paving, a new police force and fire department, and an investigation of municipal corruption that led to a more efficient system of tax collection. During a smallpox epidemic in 1881-1882, he organized the free vaccination of citizens, holding the number of deaths to twenty-seven. His fiscally honest administration reduced a $350,000 city debt to $20,000 at the same time that it increased the budget paid for city services from $68,000 to $120,000.

In 1879 Powderly became head of the fledgling Knights of Labor, which he built into the nation's largest labor organization. Declining to run for a fourth term as mayor, he devoted his energies after 1884 to the union, which by 1886 boasted a membership of more than a half million.

The Knights had swelled in membership following a successful strike against

In May 1886, the Knights mobilized a nationwide strike for an eight-hour work day - the first organized nationwide strike in American history - an initiative that Powderly did not endorse. When a bomb exploded during a rally in Chicago on May 3, killing eight policemen in the infamous Haymarket Square Riot, the Knights soon lost public support and its hold as employers mounted a determined counteroffensive against Knights job actions.

By the late 1880s, the

In 1892, Powderly supported Populist Party candidate James Weaver for president and wrote a brief prediction of what the nation would look like

Powderly spent the last years of his life in Washington, D.C., where he died in 1924. Even in his later years he remained an eloquent defender of the laboring men and women and

Beyond the Marker