Chapter 2: Steel City and Mill Towns

The steel-mill towns of Pennsylvania helped give birth to a modern industrial society. Here was where the sons and daughters of peasants, farmers, and sharecroppers became industrial workers, trading the rhythms of traditional life for the stern discipline of the factory whistle. These towns also staged the great drama of immigration, as American society was transformed by successive waves of newcomers from Europe and African-Americans from the South.

To many Americans steel-mill towns were drab, gritty, suffocating in smoke, and peopled by "foreigners." The image is not entirely false. A surface likeness extended across Johnstown,

Johnstown, Morewood,

Morewood,  Duquesne, Aliquippa,

Duquesne, Aliquippa, Bethlehem,Vandergrift, and many other mill towns. Even the great "steel city" of

Bethlehem,Vandergrift, and many other mill towns. Even the great "steel city" of  Pittsburgh was not really a metropolitan center like Chicago or New York, but a set of mill towns strung along its riverbanks. Beneath the smoke, however, one could find diversity and dynamism inside the steel city and Commonwealth's mill towns.

Pittsburgh was not really a metropolitan center like Chicago or New York, but a set of mill towns strung along its riverbanks. Beneath the smoke, however, one could find diversity and dynamism inside the steel city and Commonwealth's mill towns.

The American steel industry and its mill towns experienced explosive growth in the heyday of Andrew Carnegie and

Andrew Carnegie and  Henry Clay Frick. In the 1850s, the mills were populated typically by skilled workers from Germany, England, Ireland, or Wales. These "old stock" immigrants, often arriving with a family, sought a permanent place to settle and melded easily with native white Americans.

Henry Clay Frick. In the 1850s, the mills were populated typically by skilled workers from Germany, England, Ireland, or Wales. These "old stock" immigrants, often arriving with a family, sought a permanent place to settle and melded easily with native white Americans.

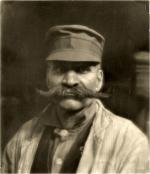

The steel towns changed decisively with the arrival of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the 1880s. Typically agricultural or town laborers, most were single men looking for temporary work or married men with a family back home. Occasionally, as in Morewood, steel companies directly recruited labor from Europe. More often, early arriving immigrants served as informal labor agents, writing glowing letters back home, providing newcomers with a helping hand, and perhaps collecting a modest fee for taking the newcomer into the mill.

arrival of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the 1880s. Typically agricultural or town laborers, most were single men looking for temporary work or married men with a family back home. Occasionally, as in Morewood, steel companies directly recruited labor from Europe. More often, early arriving immigrants served as informal labor agents, writing glowing letters back home, providing newcomers with a helping hand, and perhaps collecting a modest fee for taking the newcomer into the mill.

Such "chain migration" brought Croatian immigrants to Steelton, the industrial town outside Harrisburg planned by the Pennsylvania Railroad. Literally all the Croatians on one immigrant ship arriving at Philadelphia in 1915 were bound for Steelton. It is difficult to believe that wages as low as ten cents an hour, especially for brutal heavy labor, could attract so many, but dire conditions often prevailed in the "old country," where feudal estates were breaking up and peasants were being displaced from the land.

Dire conditions also existed in the Jim Crow South. Shunned by the white trade unions, African-American workers, many of them well skilled, formed a parallel black union movement to struggle for their rights. Even before the "great migration" during World War I doubled the black population of western Pennsylvania, African-Americans had a significant presence in Homestead, Rankin, Donora,

doubled the black population of western Pennsylvania, African-Americans had a significant presence in Homestead, Rankin, Donora,  Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, while other mill towns, including Vandergrift and Johnstown, remained "lily white."

Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, while other mill towns, including Vandergrift and Johnstown, remained "lily white."

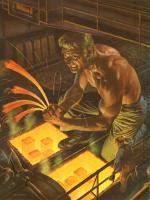

New arrivals often followed friends or kin through the mill gate and even into the same mill department. "In blast furnaces, aside from the Irish foreman, there are seldom any but Slavs or Hungarians employed," John Fitch observed of Pittsburgh around 1910.

John Fitch observed of Pittsburgh around 1910.

At Steelton, Serbians and African Americans labored in the blast furnaces, again with Irish bosses, while Croatians and Slovenians tended the open-hearth furnaces, and a force composed exclusively of Bulgarians manned the plant's internal railroad. Steelton's skilled workers making railroad switches were 87 percent American, German, English, and Irish. These divisions by ethnicity and skill bedeviled attempts to form industrial unions.

Strikes, lockouts, slow times, full-scale economic depressions, and the hope of better work elsewhere resulted in a sizable "floating population" of the least skilled, who moved on to the next mill town, to a join a railroad work crew, or to sign up with a coalmine gang. At Steelton, a group of Italians for some years spent the winter months harvesting wheat in Argentina. Many immigrants, perhaps as many as one-third, returned to the old country.

Immigrants' itinerant lives weakened their ties to any particular town or city. The presence of large numbers of single men also fueled the growth of a large "vice industry" centered on prostitution, alcohol, and gambling, which prospered in many mill towns. Homestead's Sixth Avenue hosted one of the gaudiest sin strips in America. In McKeesport, "Brick Alley" was a renowned red-light district with mostly African-American women workers.

Local town governments, dominated inevitably by "old stock" residents, responded with a mixture of fear and paternalism. Municipalities and private agencies mounted campaigns against excessive drinking, illegal gambling, disorderly wedding parties, and spirited parades held by immigrant lodges and fraternal organizations, often on Sundays. Sanitary campaigns targeted immigrants' filthy housing and personal hygene. "The buildings are dilapidated," wrote a correspondent to the Steelton Reporter of an immigrant quarter. "The scrubbing brush is also an unknown article and cleanser as soap is a perfect stranger. The stench arising when the thermometer reaches the 90s is almost unbearable to pedestrians."

A town's government reflected its mills. Where unions were strong, union men became town officials. At Homestead in 1892, John McLuckie, a union man in the Bessemer mill, was the town's burgess (executive officer) and union men dominated the town council.

Homestead in 1892, John McLuckie, a union man in the Bessemer mill, was the town's burgess (executive officer) and union men dominated the town council.

More often, however, steel companies dominated local government. Full-scale company towns such as Vandergrift or Concrete City were comparatively rare, but employers dominated most mill towns. Cambria Iron's Daniel Morrell virtually created the city of Johnstown, built extensive company housing, and for three decades directed its town council, gas and water companies, and two banks. A half century after the mill's founding, Cambria Iron still owned the town's largest hotel, much of its worker housing, a flourishing hilltop "American residential suburb," and the railroad connecting it to the city proper.

Vandergrift or Concrete City were comparatively rare, but employers dominated most mill towns. Cambria Iron's Daniel Morrell virtually created the city of Johnstown, built extensive company housing, and for three decades directed its town council, gas and water companies, and two banks. A half century after the mill's founding, Cambria Iron still owned the town's largest hotel, much of its worker housing, a flourishing hilltop "American residential suburb," and the railroad connecting it to the city proper.

Steel companies also exerted their influence over mill towns by paying for public buildings and running the town. Citizens surveying their town's company-built and/or company-managed school, library, gymnasium, swimming pool, or golf course might think twice before voting against the company.

Often enough, steel company managers sat on city councils or school boards and decided which books were shelved in the library and which groups might meet in its rooms. For decades, the YMCA and most Protestant churches solidly backed the steel companies. When Protestant churches mounted a campaign against Sunday work in the late 1800s, they aimed at shops, bars, and drugstores - but not at the steel companies with their seven-day week.

Many immigrants responded to the pervasive economic insecurities and invasive campaigns against drinking, gambling, and "disorderly" parades by intensifying their ethnic ties. Churches, lodges, mutual-aid societies, schools, athletic halls, and ethnic businesses created enclaves where immigrants were among kith and kin.

Most immigrant workers and their families lived in largely self-contained communities. Cambria City, the historic immigrant district of Johnstown, was home to ten ethnic churches, including the Byzantine Catholic Church, Saint George's Serbian Orthodox Church, and a Protestant Hungarian Reformed Church.

Cambria City, the historic immigrant district of Johnstown, was home to ten ethnic churches, including the Byzantine Catholic Church, Saint George's Serbian Orthodox Church, and a Protestant Hungarian Reformed Church.

In Pittsburgh, Italians initially clustered in the four blocks bounded by Fifth and Sixth avenues and Smithfield and Grant streets, then moved into nearby Bloomfield and East Liberty. Poles in Pittsburgh inhabited districts in Southside and "Polish Hill." Even before the "great migration" triggered by World War I, African-Americans in Pittsburgh clustered in the Hill district and Homewood-Brushton.

Beginning in World War I, a vigorous national campaign for "one hundred percent Americanism" sought to turn diverse immigrants into patriotic Americans. Not all immigrants, however, rushed at the offer. In Steelton, less than 40 percent of the nearly 1,800 foreign-born adult males had taken the first step toward U.S. citizenship by 1920.

Mill towns flourished from the mid-1930s through the mid-1970s owing to the strong steel unionism achieved during Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal and the plentiful steel profits in subsequent decades. During these good years, when many blue-collar workers achieved a middle-class lifestyle, ethnic networks remained a prime source of jobs. "The only way you got a job [was] through somebody at work who got you in," noted a Pole interviewed in the 1970s. "I mean this application, that's a big joke. They just threw them away."

No one really foresaw the collapse of the steel industry in the 1980s - in one decade, fully half of the country's steel jobs vanished - and the utter devastation of Pennsylvania's steel mill towns. They had been at the cutting edge of modern industrial society, but post-industrial society largely left them behind.

The day the Homestead Mill closed in July 1986, William Serrin followed the last workers to a bar for some reflective nostalgia. "I worked in that rusty mother for thirty-nine and one-half years," one crane man said. "Now it's gone. It's a goddamned shame."

To many Americans steel-mill towns were drab, gritty, suffocating in smoke, and peopled by "foreigners." The image is not entirely false. A surface likeness extended across

The American steel industry and its mill towns experienced explosive growth in the heyday of

The steel towns changed decisively with the

Such "chain migration" brought Croatian immigrants to Steelton, the industrial town outside Harrisburg planned by the Pennsylvania Railroad. Literally all the Croatians on one immigrant ship arriving at Philadelphia in 1915 were bound for Steelton. It is difficult to believe that wages as low as ten cents an hour, especially for brutal heavy labor, could attract so many, but dire conditions often prevailed in the "old country," where feudal estates were breaking up and peasants were being displaced from the land.

Dire conditions also existed in the Jim Crow South. Shunned by the white trade unions, African-American workers, many of them well skilled, formed a parallel black union movement to struggle for their rights. Even before the "great migration" during World War I

New arrivals often followed friends or kin through the mill gate and even into the same mill department. "In blast furnaces, aside from the Irish foreman, there are seldom any but Slavs or Hungarians employed,"

At Steelton, Serbians and African Americans labored in the blast furnaces, again with Irish bosses, while Croatians and Slovenians tended the open-hearth furnaces, and a force composed exclusively of Bulgarians manned the plant's internal railroad. Steelton's skilled workers making railroad switches were 87 percent American, German, English, and Irish. These divisions by ethnicity and skill bedeviled attempts to form industrial unions.

Strikes, lockouts, slow times, full-scale economic depressions, and the hope of better work elsewhere resulted in a sizable "floating population" of the least skilled, who moved on to the next mill town, to a join a railroad work crew, or to sign up with a coalmine gang. At Steelton, a group of Italians for some years spent the winter months harvesting wheat in Argentina. Many immigrants, perhaps as many as one-third, returned to the old country.

Immigrants' itinerant lives weakened their ties to any particular town or city. The presence of large numbers of single men also fueled the growth of a large "vice industry" centered on prostitution, alcohol, and gambling, which prospered in many mill towns. Homestead's Sixth Avenue hosted one of the gaudiest sin strips in America. In McKeesport, "Brick Alley" was a renowned red-light district with mostly African-American women workers.

Local town governments, dominated inevitably by "old stock" residents, responded with a mixture of fear and paternalism. Municipalities and private agencies mounted campaigns against excessive drinking, illegal gambling, disorderly wedding parties, and spirited parades held by immigrant lodges and fraternal organizations, often on Sundays. Sanitary campaigns targeted immigrants' filthy housing and personal hygene. "The buildings are dilapidated," wrote a correspondent to the Steelton Reporter of an immigrant quarter. "The scrubbing brush is also an unknown article and cleanser as soap is a perfect stranger. The stench arising when the thermometer reaches the 90s is almost unbearable to pedestrians."

A town's government reflected its mills. Where unions were strong, union men became town officials. At

More often, however, steel companies dominated local government. Full-scale company towns such as

Steel companies also exerted their influence over mill towns by paying for public buildings and running the town. Citizens surveying their town's company-built and/or company-managed school, library, gymnasium, swimming pool, or golf course might think twice before voting against the company.

Often enough, steel company managers sat on city councils or school boards and decided which books were shelved in the library and which groups might meet in its rooms. For decades, the YMCA and most Protestant churches solidly backed the steel companies. When Protestant churches mounted a campaign against Sunday work in the late 1800s, they aimed at shops, bars, and drugstores - but not at the steel companies with their seven-day week.

Many immigrants responded to the pervasive economic insecurities and invasive campaigns against drinking, gambling, and "disorderly" parades by intensifying their ethnic ties. Churches, lodges, mutual-aid societies, schools, athletic halls, and ethnic businesses created enclaves where immigrants were among kith and kin.

Most immigrant workers and their families lived in largely self-contained communities.

In Pittsburgh, Italians initially clustered in the four blocks bounded by Fifth and Sixth avenues and Smithfield and Grant streets, then moved into nearby Bloomfield and East Liberty. Poles in Pittsburgh inhabited districts in Southside and "Polish Hill." Even before the "great migration" triggered by World War I, African-Americans in Pittsburgh clustered in the Hill district and Homewood-Brushton.

Beginning in World War I, a vigorous national campaign for "one hundred percent Americanism" sought to turn diverse immigrants into patriotic Americans. Not all immigrants, however, rushed at the offer. In Steelton, less than 40 percent of the nearly 1,800 foreign-born adult males had taken the first step toward U.S. citizenship by 1920.

Mill towns flourished from the mid-1930s through the mid-1970s owing to the strong steel unionism achieved during Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal and the plentiful steel profits in subsequent decades. During these good years, when many blue-collar workers achieved a middle-class lifestyle, ethnic networks remained a prime source of jobs. "The only way you got a job [was] through somebody at work who got you in," noted a Pole interviewed in the 1970s. "I mean this application, that's a big joke. They just threw them away."

No one really foresaw the collapse of the steel industry in the 1980s - in one decade, fully half of the country's steel jobs vanished - and the utter devastation of Pennsylvania's steel mill towns. They had been at the cutting edge of modern industrial society, but post-industrial society largely left them behind.

The day the Homestead Mill closed in July 1986, William Serrin followed the last workers to a bar for some reflective nostalgia. "I worked in that rusty mother for thirty-nine and one-half years," one crane man said. "Now it's gone. It's a goddamned shame."