Chapter Two: Economics of Revolution

On the eve of the American Revolution, Pennsylvania had a thriving economy and comparatively good relations with Great Britain. Unlike the plantation economies of Virginia and South Carolina or New England's emphasis on trade and commerce, Pennsylvania boasted a highly diversified economy based on farming, commerce and finance, and some manufacturing. Its fertile lands made the colony a productive region for the commercial farming of flax, hemp, wheat, corn and other grains, especially in the southeastern quarter, which was known as the "Breadbasket of North America." An abundance of iron ore, limestone, wood, and water allowed Pennsylvania to lead the colonies in the making of iron, which would be critical to the military success of the patriot cause.

Philadelphia, second only to London in the economic influence it wielded throughout the British Empire, was the financial center of America. Through its port flowed the crops and timber of Pennsylvania's hinterland. The city's merchants dominated the Atlantic trade with a lucrative network that connected them with merchants in Europe, the West Indies, New England, and the southern colonies. Urban entrepreneurs circulated in the city's taverns and coffee houses to propose maritime ventures or engage in land speculation. These social and commercial centers served as a de facto stock exchange and supplied the capital to finance the colony's impressive economic infrastructure and ongoing development.

The British tax and revenue laws that led to the American Revolution did not have as devastating an impact on Pennsylvania's economy as they did in other colonies. The natural resources and commercial products that made the colony the "best poor man's country in the world" in the eighteenth century largely escaped British regulatory or revenue-raising measures. Pennsylvania's "staple" products -wheat, flaxseed, flour and ship biscuit (a hard biscuit that kept better than bread) - were neither regulated in terms of their market flow nor taxed in the ways that New England's molasses and rum trades were after 1764.

Marketing wheat did not generate the kind of massive commercial debt to Britain that alienated planter elites in the Chesapeake tobacco kingdom after 1750. Instead, Philadelphia merchants in the 1750s found new markets for their colony's wheat in southern Europe. While Pennsylvanians objected in principle to "Stamp" taxes and duties on luxury items as much as people in other colonies, they were harder pressed to see harm in the new imperial revenue measures when they considered the profits they were making.

To be sure, Pennsylvania's natural resources and commercial products became critical to the patriot cause when war came to the colony. The Continental Army had to retain control of the colony's rich farmlands in order to secure the foodstuffs necessary to sustain its troops during the exhausting Philadelphia campaign and the long hard winter that followed. Gristmills, which processed wheat for domestic consumption and export, dotted the streams of every township. Those owned by patriot farmers provided flour for the Continental Army. Others, like the Quaker-founded

Just as important to the success of the patriot cause were the iron forges, furnaces, and plantations that provided muskets, shot, and cannon for Washington's army. Critical to the economic infrastructure of Pennsylvania, these ironworks were fiercely contested during the Revolution.

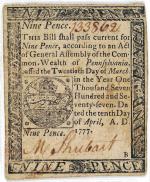

Merchant capital was indispensable to the prosecution of the war, especially given the increasingly worthless Continental currency, the inability of Congress to supply the army in the absence of any taxing power, and the price fixing of crops and other goods by merchants bent on profiting from both armies. Profiteering on provisions sold to civilians led in October, 1779, to an armed assault on the Philadelphia residence of

The superintendent of finance for the Continental Congress, Robert Morris also served as purchasing agent of military supplies for Pennsylvania's troops. Forced to relocate to

Similarly,

Women also made important contributions to the war effort by leading boycotts of British manufactured products, providing indispensable military intelligence, and organizing cottage industries to produce uniforms, gunpowder, and shot. Lydia Darrah, a Quaker matron living in British-occupied Philadelphia, warned Washington, encamped at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78, of a Redcoat force reconnoitering the area for his army. Sarah Bache, the daughter of Benjamin Franklin, organized 2,000 Philadelphia women to sew clothing for the Continental soldiers, and

At the same time the War for American Independence left the Pennsylvania economy in ruin. Wracked by persistent warfare, many who settled on the northern and western frontiers went broke after their farms were ravaged in vicious fighting. In the southeast, the City of Philadelphia fell into economic havoc. State government was unable to pay debts to mutinous soldiers, maintain the value of the currency, or repair the buildings devastated by the British occupation. Some of the city's residents who lost their homes had no hope of any compensation for their loss.

Once independent of Great Britain, Philadelphia's merchants had to build new trading relationships with other nations and strengthen existing ones with France and the Caribbean. When several hundred Pennsylvania soldiers marched on Philadelphia in June 1783 and demanded back pay, Congress narrowly escaped, first to Trenton, then Princeton, and finally New York City.

Once the end of the Revolutionary War secured the desired outcome of an independent United States, the considerable challenge of nation-building still remained. Pennsylvania, like the United States as a whole, paid a serious price for the revolution in terms of declining per capita income, economic growth, and other financial hardships. It would take more than decade for the state's economy to recover from the war.