![header=[Marker Text] body=[An early graduate of the Institute for Colored Youth, Catto, who lived here, was an educator, a Union army major, and a political organizer. In 1871 he was assassinated by street rioters while urging African-Americans to vote. His death was widely mourned locally. ] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-38D-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0m1b4-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Octavius V. Catto [Education]

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

812 South St., Philadelphia

Behind the Marker

Between the early 1870s and 1950s Philadelphia was controlled by one of the nation's most powerful and long-lived Republican city "machines." The Republican Party first took control of the city in the 1870s when it recruited several critical bodies of voters: businessmen and workers who wanted the high tariff supported by the GOP to protect their products and jobs from foreign competition, Civil War veterans who identified with party of Lincoln and Union, and poorer citizens seeking jobs in the construction, public utilities–especially the Philadelphia Gas Company–and transportation industries. African Americans could be counted among both the veterans and the poorer citizens. Their leader in the immediate post-Civil War era was schoolteacher Octavius Catto.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Catto moved to Philadelphia as a boy with his father, a Presbyterian minister, who made sure that he received an excellent education at the Institute for Colored Youth. Graduating as the valedictorian, he joined the school's faculty and taught English, mathematics, and classics. Catto's love of learning appeared in his founding of the Banneker Literary Institute, named after Benjamin Banneker, the black surveyor and printer who had helped lay out the boundaries of Washington, D. C.

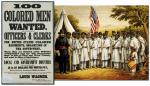

During the Civil War, when the state requested emergency volunteers during Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania during the summer of 1863, Catto raised a company of black troops. The commander of the state volunteers, however, refused their service, as the state had not yet authorized the recruitment of black soldiers. When the state provided for their enlistment later that year, Catto worked tirelessly in Philadelphia to enroll many of the first soldiers, many of whom mustered at Camp William Penn, located on abolitionist Lucretia Mott's estate in Elkins Park just outside the city. In recognition of his service, Philadelphia Republicans admitted him to the prestigious Union League, and the Library Company, founded by Benjamin Franklin, elected him a member.

Lucretia Mott's estate in Elkins Park just outside the city. In recognition of his service, Philadelphia Republicans admitted him to the prestigious Union League, and the Library Company, founded by Benjamin Franklin, elected him a member.

After the war, Catto became a leader in the fight for black Pennsylvanians' civil rights, and one of the city's most prominent African Americans. The Union League honored Catto and Robert Purvis as Philadelphia's greatest black citizens. He played and coached for Philadelphia's Pythian baseball club, a black team that almost always won. And he pushed for a state statute desegregating public transportation in Philadelphia, which the state legislature passed in 1867.

Robert Purvis as Philadelphia's greatest black citizens. He played and coached for Philadelphia's Pythian baseball club, a black team that almost always won. And he pushed for a state statute desegregating public transportation in Philadelphia, which the state legislature passed in 1867.

In 1864, Philadelphians had voted heavily for Lincoln for president over Philadelphian and Democratic candidate George McClellan. Their support of the war and Lincoln, however, did not mean that they supported racial equality. The state of Pennsylvania had revoked African Americans' right to vote in its 1838 Constitution, and did not restore that right until October 1870, because the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution compelled it to do so.

In Philadelphia, as in the South under Reconstruction, African Americans could only vote safely when United States troops patrolled the streets and protected the polling places from gangs of thugs who worked for the Democratic Party machine that still ran the city. The following year, the marines were gone and the Democrats made it clear that they would prevent blacks from voting.

The key city race in 1871 was for district attorney. Republican candidate William Mann promised to end racial intimidation and the Democratic machine's corrupt rule. The Democrats, in turn, accused the Republicans of doing what they themselves did to win elections: buying votes, repeated voting, and trading votes for drinks. Early on Election Day, October 10, Democratic gangs intimidated voters at the polls and killed several blacks. Catto, now a major in the Pennsylvania National Guard, was preparing to get help from other officers to round up their men and end the violence.

As he was walking home to don his uniform, he was shot in the back by Frank Kelly, a friend of Democratic boss William McMullen. That day the Republicans trounced the Democrats, in part due to public outrage as word of Catto's death spread. The GOP would rule Philadelphia for the next eight decades.

On October 16, Catto received a public funeral second in size only to that of President Lincoln's in 1865. White and black officials alike spoke honoring his life and condemning his murder. He was buried, at public expense, in his military uniform in Mt. Lebanon Cemetery in a Masonic ceremony. (Catto was also a Mason.) Meanwhile, his assassin escaped to Chicago. Not arrested until 1877, McMullen was then brought back to Philadelphia and acquitted.

Catto did not die in vain: henceforth, blacks could vote in Philadelphia. Although their numbers were small, less than 4 percent of the city's population in the late 1800s, Republican politicians courted their votes, but in exchange rewarded them only with minor patronage positions and a few symbolic elected offices. The black vote, in Philadelphia and throughout the Commonwealth, remained firmly in the Republican column until the Great Depression, when the promise of New Deal benefits and the leadership of Pittsburgh Courier publisher Robert Vann fueled a mass defection to the Democrat Party.

Robert Vann fueled a mass defection to the Democrat Party.

To learn more about Catto and the history of African-American baseball in Pennsylvania, click here.

here.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Catto moved to Philadelphia as a boy with his father, a Presbyterian minister, who made sure that he received an excellent education at the Institute for Colored Youth. Graduating as the valedictorian, he joined the school's faculty and taught English, mathematics, and classics. Catto's love of learning appeared in his founding of the Banneker Literary Institute, named after Benjamin Banneker, the black surveyor and printer who had helped lay out the boundaries of Washington, D. C.

During the Civil War, when the state requested emergency volunteers during Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania during the summer of 1863, Catto raised a company of black troops. The commander of the state volunteers, however, refused their service, as the state had not yet authorized the recruitment of black soldiers. When the state provided for their enlistment later that year, Catto worked tirelessly in Philadelphia to enroll many of the first soldiers, many of whom mustered at Camp William Penn, located on abolitionist

After the war, Catto became a leader in the fight for black Pennsylvanians' civil rights, and one of the city's most prominent African Americans. The Union League honored Catto and

In 1864, Philadelphians had voted heavily for Lincoln for president over Philadelphian and Democratic candidate George McClellan. Their support of the war and Lincoln, however, did not mean that they supported racial equality. The state of Pennsylvania had revoked African Americans' right to vote in its 1838 Constitution, and did not restore that right until October 1870, because the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution compelled it to do so.

In Philadelphia, as in the South under Reconstruction, African Americans could only vote safely when United States troops patrolled the streets and protected the polling places from gangs of thugs who worked for the Democratic Party machine that still ran the city. The following year, the marines were gone and the Democrats made it clear that they would prevent blacks from voting.

The key city race in 1871 was for district attorney. Republican candidate William Mann promised to end racial intimidation and the Democratic machine's corrupt rule. The Democrats, in turn, accused the Republicans of doing what they themselves did to win elections: buying votes, repeated voting, and trading votes for drinks. Early on Election Day, October 10, Democratic gangs intimidated voters at the polls and killed several blacks. Catto, now a major in the Pennsylvania National Guard, was preparing to get help from other officers to round up their men and end the violence.

As he was walking home to don his uniform, he was shot in the back by Frank Kelly, a friend of Democratic boss William McMullen. That day the Republicans trounced the Democrats, in part due to public outrage as word of Catto's death spread. The GOP would rule Philadelphia for the next eight decades.

On October 16, Catto received a public funeral second in size only to that of President Lincoln's in 1865. White and black officials alike spoke honoring his life and condemning his murder. He was buried, at public expense, in his military uniform in Mt. Lebanon Cemetery in a Masonic ceremony. (Catto was also a Mason.) Meanwhile, his assassin escaped to Chicago. Not arrested until 1877, McMullen was then brought back to Philadelphia and acquitted.

Catto did not die in vain: henceforth, blacks could vote in Philadelphia. Although their numbers were small, less than 4 percent of the city's population in the late 1800s, Republican politicians courted their votes, but in exchange rewarded them only with minor patronage positions and a few symbolic elected offices. The black vote, in Philadelphia and throughout the Commonwealth, remained firmly in the Republican column until the Great Depression, when the promise of New Deal benefits and the leadership of Pittsburgh Courier publisher

To learn more about Catto and the history of African-American baseball in Pennsylvania, click

Beyond the Marker