![header=[Marker Text] body=[First uniformed state police force of its kind in the nation, created by an Act of the General Assembly May 2, 1905, signed by Governor Samuel Pennypacker. The force was formed in response to concern over labor and capital unrest, especially the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902. At this site the State Police established its first training academy in 1924. Cadets were trained here for 36 years until a new academy was built north of Hershey] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-2D1-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k3k3-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Pennsylvania State Police [Bituminous Coal]

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Dauphin

Marker Location:

Hershey School District Memorial Field Complex, Cocoa Ave., Hershey

Dedication Date:

September 13, 2005

Behind the Marker

From Governor Pennypacker's perspective, the State Police provided a practical solution to a practical problem: enforcing law and order in the Commonwealth's vast, frequently isolated, and often under-served rural districts. But Pennypacker's comments concealed a more complicated political reality-namely, the increasingly violent and costly labor disputes that then plagued the state's anthracite and bituminous coal fields. Supporters envisioned the State Police as a sort of quick response unit, capable of being dispatched to trouble spots at a moment's notice. But to labor organizers and many Pennsylvania coal miners, the prospects of state-controlled police portended a more menacing sign-the unprecedented use of state power to crush dissent and abrogate workers' civil rights.

During the nineteenth century, the enforcement of law and order in the state's vast coal fields had been consigned to individual mine operators. An 1866 law authorizing the Coal and Iron Police allowed private companies to purchase commissions from the state which conferred police powers. Companies assigned commissions to anyone whom they hired. The law was intended to force private companies to bear the cost of protecting their property. But having companies pay for the hired guns ensured that the Coal and Iron Police would enforce the will of the mine owners.

Politicians such as Governor Pennypacker were less concerned with the abuses of civil rights by the Coal and Iron Police than the system's administrative limitations. The prolonged 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike exposed the lack of central control. During the five-month-long dispute, the Coal and Iron Police proved difficult to coordinate and ultimately incapable of ending the strike. It took calling out the National Guard-and the intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt-to end the conflict and put the mines back in operation. A federal commission that investigated the handling of the strike recommended the creation of a uniformed cavalry force to end the inefficiencies.

1902 Anthracite Coal Strike exposed the lack of central control. During the five-month-long dispute, the Coal and Iron Police proved difficult to coordinate and ultimately incapable of ending the strike. It took calling out the National Guard-and the intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt-to end the conflict and put the mines back in operation. A federal commission that investigated the handling of the strike recommended the creation of a uniformed cavalry force to end the inefficiencies.

Union leaders were understandably anxious. Although a State Constabulary had been promoted as a neutral body, labor officials feared the force would be called out on behalf of mine operators and lobbied hard against legislation that would establish the state police. Despite vocal objections, the General Assembly approved the legislation, and in 1905 Governor Pennypacker signed the law creating the Pennsylvania State Constabulary, the first uniformed police organization of its kind in the country and a model for other states.

The first class of State Police, recruited largely from among former U.S. military men, went out on active duty in early 1906 and was assigned to barracks strategically located in or near the state's vast coal fields: Greensburg, Punxsutawney, Wilkes-Barre, and Reading. The State Police engaged in a variety of law-enforcement duties, from tracking poachers to breaking up gambling rackets, but its primary duty became maintaining peace during labor disputes in the bituminous coal fields. Before the advent of motorized vehicles, the State Police patrolled almost entirely on horseback.

To supporters, the new State Constabulary was a model of propriety and efficiency. "The brilliant success of the Pennsylvania Constabulary shows what can be done by a very small body of disciplined, mounted State Police," the New York Tribune opined. "Time and again, fifty to one hundred troopers have done what it used to take a couple of regiments to do in the trouble breeding coal mining districts." They also had the advantage, compared to the Coal and Iron Police, of professional neutrality. "The State Police represent no class or condition, no prejudice or interest, nothing but the sovereign majesty of the law," the Philadelphia Ledger wrote.

But many coal miners in the bituminous coal fields, where state police were a nearly constant presence, begged to differ. In 1910 state representative James Mauer, an open critic of the state constabulary, collected testimony from ordinary citizens that contradicted official pronouncements. Residents of Madison, a small coal-company town in Westmoreland County, told Mauer how the State Police had dispersed a labor meeting at gunpoint and framed labor organizers on false charges. "Now if this is justice and freedom in a free country-I call it Russian-in fact, it is worse than Russia. The coal barons are the czars and the State Police are the Cossacks. "[Citizens of Madison to James H. Mauer, 22 February 1911 in Pennsylvania State Federation of Labor, The American Cossack" Mauer submitted the testimony to the General Assembly for consideration, but a bill he introduced in 1911 calling for the force's repeal was defeated.

"[Citizens of Madison to James H. Mauer, 22 February 1911 in Pennsylvania State Federation of Labor, The American Cossack" Mauer submitted the testimony to the General Assembly for consideration, but a bill he introduced in 1911 calling for the force's repeal was defeated.

During the next two decades the State Police continued to be active in labor disputes, especially those in the bituminous coal fields. As a matter of policy and practice, they continued to take the side of capital over labor. During the course of the 1922 coal strike, for instance, the United Miner Workers of America obtained a copy of a secret memo written by the state police superintendent and addressed to local mine operators; among other pieces of information, the state police requested the names and addresses "of all known radicals," presumably so that they could be harassed. Lynn G. Adams, Harrisburg, to [Coal Companies], 18 March 1922, UMWA, District 2, UMWA Records But as the strike unfolded, the commander assigned to Windber (see

Lynn G. Adams, Harrisburg, to [Coal Companies], 18 March 1922, UMWA, District 2, UMWA Records But as the strike unfolded, the commander assigned to Windber (see  Windber Strike of 1922-1923) defied all expectations by instructing his detail to enforce laws impartially, even to the point of protecting striking miners from private police force thugs. It would be years before such actions would become the rule rather than the exception.

Windber Strike of 1922-1923) defied all expectations by instructing his detail to enforce laws impartially, even to the point of protecting striking miners from private police force thugs. It would be years before such actions would become the rule rather than the exception.

To learn more about the early history of the Pennsylvania State Police: click here

click here

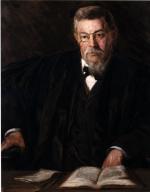

"I found that no power existed . . . to enforce the law of the state. I looked about to see what . . . instruments on whose loyalty and obedience I could truly rely. And I perceived three such instruments-my private secretary, a very small man, my woman stenographer and the janitor, a Negro. So I made the state police."

-Governor Samuel Pennypacker

From Governor Pennypacker's perspective, the State Police provided a practical solution to a practical problem: enforcing law and order in the Commonwealth's vast, frequently isolated, and often under-served rural districts. But Pennypacker's comments concealed a more complicated political reality-namely, the increasingly violent and costly labor disputes that then plagued the state's anthracite and bituminous coal fields. Supporters envisioned the State Police as a sort of quick response unit, capable of being dispatched to trouble spots at a moment's notice. But to labor organizers and many Pennsylvania coal miners, the prospects of state-controlled police portended a more menacing sign-the unprecedented use of state power to crush dissent and abrogate workers' civil rights.

During the nineteenth century, the enforcement of law and order in the state's vast coal fields had been consigned to individual mine operators. An 1866 law authorizing the Coal and Iron Police allowed private companies to purchase commissions from the state which conferred police powers. Companies assigned commissions to anyone whom they hired. The law was intended to force private companies to bear the cost of protecting their property. But having companies pay for the hired guns ensured that the Coal and Iron Police would enforce the will of the mine owners.

Politicians such as Governor Pennypacker were less concerned with the abuses of civil rights by the Coal and Iron Police than the system's administrative limitations. The prolonged

Union leaders were understandably anxious. Although a State Constabulary had been promoted as a neutral body, labor officials feared the force would be called out on behalf of mine operators and lobbied hard against legislation that would establish the state police. Despite vocal objections, the General Assembly approved the legislation, and in 1905 Governor Pennypacker signed the law creating the Pennsylvania State Constabulary, the first uniformed police organization of its kind in the country and a model for other states.

The first class of State Police, recruited largely from among former U.S. military men, went out on active duty in early 1906 and was assigned to barracks strategically located in or near the state's vast coal fields: Greensburg, Punxsutawney, Wilkes-Barre, and Reading. The State Police engaged in a variety of law-enforcement duties, from tracking poachers to breaking up gambling rackets, but its primary duty became maintaining peace during labor disputes in the bituminous coal fields. Before the advent of motorized vehicles, the State Police patrolled almost entirely on horseback.

To supporters, the new State Constabulary was a model of propriety and efficiency. "The brilliant success of the Pennsylvania Constabulary shows what can be done by a very small body of disciplined, mounted State Police," the New York Tribune opined. "Time and again, fifty to one hundred troopers have done what it used to take a couple of regiments to do in the trouble breeding coal mining districts." They also had the advantage, compared to the Coal and Iron Police, of professional neutrality. "The State Police represent no class or condition, no prejudice or interest, nothing but the sovereign majesty of the law," the Philadelphia Ledger wrote.

But many coal miners in the bituminous coal fields, where state police were a nearly constant presence, begged to differ. In 1910 state representative James Mauer, an open critic of the state constabulary, collected testimony from ordinary citizens that contradicted official pronouncements. Residents of Madison, a small coal-company town in Westmoreland County, told Mauer how the State Police had dispersed a labor meeting at gunpoint and framed labor organizers on false charges. "Now if this is justice and freedom in a free country-I call it Russian-in fact, it is worse than Russia. The coal barons are the czars and the State Police are the Cossacks.

During the next two decades the State Police continued to be active in labor disputes, especially those in the bituminous coal fields. As a matter of policy and practice, they continued to take the side of capital over labor. During the course of the 1922 coal strike, for instance, the United Miner Workers of America obtained a copy of a secret memo written by the state police superintendent and addressed to local mine operators; among other pieces of information, the state police requested the names and addresses "of all known radicals," presumably so that they could be harassed.

To learn more about the early history of the Pennsylvania State Police:

Beyond the Marker