![header=[Marker Text] body=[Site of Gen. John Neville's mansion, burned to the ground by insurgents during a major escalation of violence in the Whiskey Rebellion, July 16-17, 1794. Gen. Neville was Inspector of Revenue under President Washington. In the two-day battle, Neville with his slaves and a small federal detachment met a force of over 500 rebels. Two opposition leaders, Oliver Miller and James McFarlane, were killed.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-29C-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h9k4-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Bower Hill

Region:

Pittsburgh Region

County:

Allegheny

Marker Location:

Kane Blvd., Scott Twp. NE of Bridgeville

Dedication Date:

August 21, 1996

Behind the Marker

In the 1790s, Bower Hill was perhaps the greatest Pennsylvania mansion west of the Allegheny Mountains. Built by General John Neville, it sat high on a hill, and towered over the residences of Neville's neighbors, most of whom lived in simple log houses. The interior was equally impressive. Neville had imported furnishings from Europe, carpeted every room, painted and plastered his walls - on which he hung more than two dozens paintings - and filled his library with a large collections of books, maps, and weapons. In 1794, Bower Hill, appropriately, would also become the site of the most important clash in the Whiskey Rebellion, for without Neville, the rebellion might never have occurred.

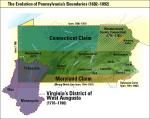

To Neville, Bower Hill well represented his high social standing and valuable service to the nation. Born in Virginia in 1731 to a wealthy planter, he had earned 1,000 acres in the Pittsburgh area by fighting in Lord Dunmore's War in 1774. At that time, Virginia had claimed much of southwestern Pennsylvania and battled the region's Native Americans to make sure that Virginia beat Pennsylvania to the forks of the Ohio River and the vast resources of the Ohio River valley. When Congress awarded Pennsylvania the territory in the 1780s, it honored existing Virginia land claims, including those of Neville and George Washington. Despite his wealth and allegiance to the Federalist Party, Neville was generous to the poor and generally popular among the frontier settlers, whose political sentiments were strongly anti-Federalist.

George Washington. Despite his wealth and allegiance to the Federalist Party, Neville was generous to the poor and generally popular among the frontier settlers, whose political sentiments were strongly anti-Federalist.

When Congress passed a federal excise tax on whiskey in 1791, Neville was Washington's natural choice to collect the revenues. He had served bravely during the American Revolution at the battles of Trenton, Germantown, Monmouth, and Princeton, and endured the winter at Valley Forge. At first, Neville had opposed the excise, which led its opponents to charge that he had been bribed to accept the post. Once he accepted the post, however, he became the only tax collector in the country who tried to enforce the law. In Kentucky, for example, the newly formed Bourbon distilleries simply went on producing untaxed. Neville, however, was not one to bow to opposition, or to threats.

In the fall of 1791, shortly after the passage of the whiskey tax, Neville reported to the president that those who petitioned the federal government for a repeal of the tax were really "ambitious politicians fishing for a place in Congress." He confided that "the matter lay in the hands of the rabble," but "did not think that it would grow to any height." But as the tar and feathering of tax collectors increased, Neville began to fear for his own safety. He now imagined a conspiracy between his elite opponents like Albert Gallatin,

Albert Gallatin,  William Findley, and John Smilie, and the "rabble" led by

William Findley, and John Smilie, and the "rabble" led by  David Bradford, a member of the local elite. Stubborn and proud by nature, Neville refused to resign. Instead, he requested that the federal government provide him with an armed force to collect the tax.

David Bradford, a member of the local elite. Stubborn and proud by nature, Neville refused to resign. Instead, he requested that the federal government provide him with an armed force to collect the tax.

Assaults on western Pennsylvania's excise men prevented the federal government from collecting the whiskey tax in that region in 1792 and 1793. Gallatin and other frontier leaders for a short while calmed the uproar by petitioning the federal government for a repeal of the tax and holding public gatherings for angry farmers to vent their rage. But federal officials mistakenly interpreted their actions as "fomenting" rather than "mediating" the frontier unrest. The conflict exploded in July 1794, when a federal marshal, David Lenox, began to issue writs ordering violators of the tax to Philadelphia for trial. Lenox experienced no problems collecting the tax until he arrived in Allegheny County, where he met his first tax resister. Lenox's arrest of the farmer, infuriated people in the region, for it took two weeks to travel from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, where westerners would be tried by unsympathetic easterners rather than a local jury of their peers, which would almost certainly acquit them or deadlock in a hung jury.

On July 16, some 500 angry men led by Oliver Miller Jr. and James McFarlane marched to Bower Hill to confront Neville and demand his resignation as Inspector of Revenue. There, they were met by the general's armed slaves and a small detachment of soldiers he had requested from the federal government to protect his property. Soon the guns were blazing, and Bower Hill and its barn were on fire. When the dust settled the following day, Miller, McFarlane and an army officer were dead and Bower Hill had burnt to the ground.

Back east, the battle at Bower Hill confirmed suspicions that the rabble out west were intent upon violent rebellion, especially after David Bradford, leading the more radical rebels, vowed death to revenue collectors and secession from the Union if President Washington attempted to enforce the hated excise tax. In response, the President stated in a message from the Espy House that an army must be sent to the region to protect the Republic. After the rebellion subsided, Neville returned to the area although Bower Hill had been destroyed. Refusing to resign his commission, he remained in Allegheny County until his death in 1803.

Espy House that an army must be sent to the region to protect the Republic. After the rebellion subsided, Neville returned to the area although Bower Hill had been destroyed. Refusing to resign his commission, he remained in Allegheny County until his death in 1803.

To Neville, Bower Hill well represented his high social standing and valuable service to the nation. Born in Virginia in 1731 to a wealthy planter, he had earned 1,000 acres in the Pittsburgh area by fighting in Lord Dunmore's War in 1774. At that time, Virginia had claimed much of southwestern Pennsylvania and battled the region's Native Americans to make sure that Virginia beat Pennsylvania to the forks of the Ohio River and the vast resources of the Ohio River valley. When Congress awarded Pennsylvania the territory in the 1780s, it honored existing Virginia land claims, including those of Neville and

When Congress passed a federal excise tax on whiskey in 1791, Neville was Washington's natural choice to collect the revenues. He had served bravely during the American Revolution at the battles of Trenton, Germantown, Monmouth, and Princeton, and endured the winter at Valley Forge. At first, Neville had opposed the excise, which led its opponents to charge that he had been bribed to accept the post. Once he accepted the post, however, he became the only tax collector in the country who tried to enforce the law. In Kentucky, for example, the newly formed Bourbon distilleries simply went on producing untaxed. Neville, however, was not one to bow to opposition, or to threats.

In the fall of 1791, shortly after the passage of the whiskey tax, Neville reported to the president that those who petitioned the federal government for a repeal of the tax were really "ambitious politicians fishing for a place in Congress." He confided that "the matter lay in the hands of the rabble," but "did not think that it would grow to any height." But as the tar and feathering of tax collectors increased, Neville began to fear for his own safety. He now imagined a conspiracy between his elite opponents like

Assaults on western Pennsylvania's excise men prevented the federal government from collecting the whiskey tax in that region in 1792 and 1793. Gallatin and other frontier leaders for a short while calmed the uproar by petitioning the federal government for a repeal of the tax and holding public gatherings for angry farmers to vent their rage. But federal officials mistakenly interpreted their actions as "fomenting" rather than "mediating" the frontier unrest. The conflict exploded in July 1794, when a federal marshal, David Lenox, began to issue writs ordering violators of the tax to Philadelphia for trial. Lenox experienced no problems collecting the tax until he arrived in Allegheny County, where he met his first tax resister. Lenox's arrest of the farmer, infuriated people in the region, for it took two weeks to travel from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, where westerners would be tried by unsympathetic easterners rather than a local jury of their peers, which would almost certainly acquit them or deadlock in a hung jury.

On July 16, some 500 angry men led by Oliver Miller Jr. and James McFarlane marched to Bower Hill to confront Neville and demand his resignation as Inspector of Revenue. There, they were met by the general's armed slaves and a small detachment of soldiers he had requested from the federal government to protect his property. Soon the guns were blazing, and Bower Hill and its barn were on fire. When the dust settled the following day, Miller, McFarlane and an army officer were dead and Bower Hill had burnt to the ground.

Back east, the battle at Bower Hill confirmed suspicions that the rabble out west were intent upon violent rebellion, especially after David Bradford, leading the more radical rebels, vowed death to revenue collectors and secession from the Union if President Washington attempted to enforce the hated excise tax. In response, the President stated in a message from the