![header=[Marker Text] body=[President, Continental Congress, 1787; member, 1785-87. First Governor of the Northwest Territory (lying between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers), 1787-1802. Earlier, he was Westmoreland County Court Justice after the county's formation in 1773, and Major General in the Revolutionary War, 1777. A native of Thurso, Scotland, he lived his last years on Chestnut Ridge, near Ligonier, and is buried just east of this marker.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-292-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h9h0-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

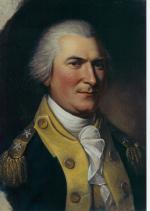

Arthur St. Clair

Region:

Laurel Highlands/Southern Alleghenies

County:

Westmoreland

Marker Location:

St. Clair Park, North Main Street, Greensburg

Dedication Date:

October 25, 1995

Behind the Marker

Born in Scotland in 1731 to a prosperous family, Arthur St. Clair was educated to be a physician at the University of Edinburgh before the attractions of the military life took him to America. There he served in the French and Indian War as a lieutenant in the British forces. While in Boston, he met the wealthy Phoebe Bayard, whom he married in 1760, and then moved to a large estate in the Ligonier Valley of Pennsylvania, which he had visited and admired during the war.

As a leading citizen of the region and judge in Westmoreland County (formed in 1773), St. Clair negotiated some failed treaties with the Indians of the Ohio Valley and tried, with equal lack of success, to evict Virginians who also claimed what is now western Pennsylvania for their state. When the War for Independence broke out, St. Clair headed east, and soon rose to the rank of major general.

In 1777 his failure to fortify Mt. Defiance enabled the British under General John Burgoyne to take New York's Fort Ticonderoga and resulted in his own court-martial. Cleared of the charges he resigned from the service. In the meanwhile, he had staunchly opposed the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, which vested nearly all power in the state assembly. After the war, he helped found the Society of Cincinnati, where revolutionary officers and their descendants could celebrate their achievements, and served as a Pennsylvania delegate to Congress, and as its President from 1785 to 1787.

At the end of the American Revolution, Great Britain had ceded a vast area to the United States called the Northwest Territories: a region that stretched from Pennsylvania's western border to what is now the state of Minnesota. The United States wanted white Americans to populate the area to counter British, Spanish, and Native American claims to the region. And it could speed settlement by using some of those lands to compensate unpaid veterans and people who had loaned the government money during the war. But the states disputed ownership of millions of acres west of the Appalachians. The territory raised some daunting questions. How should the land be distributed or sold? Who should govern the settlements of independent-minded frontiersmen and their families? Should they be incorporated into existing states? Remain territories in which residents had only partial rights? If added to the union as new states, under what terms should they be admitted?

Justly criticized for its impotence in foreign and economic affairs, the Confederation government was remarkably successful in sorting things out in the west. It convinced the states to give up their claims to the western lands, and voided the overlapping individual and company land claims they had authorized in the region. Virginia's cession of land to Pennsylvania was especially important, because Virginia insisted Congress void all private, previous claims to western lands. It transferred what little remained of the United States army to the frontier in the hopes of taking actual possession of the land from the Indians.

In 1785, the Confederation government passed the Land Ordinance which provided for the survey of newly incorporated lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which established a system of government for the region and defined the process for the creation and admission of new states that we still follow today.

As a western Pennsylvanian who had already negotiated with Indians in the Ohio Valley, St. Clair was Congress's logical choice to be the Northwest Territories" first governor. Although later he would regard himself as "a poor devil banished to another planet," he at first welcomed the post in the hope of recovering the fortune that he had lost during the American Revolution.

St. Clair's first problem was that the Ohio Valley Indians had repudiated treaties negotiated by some of them - illegitimately, many claimed - that gave away much of the territory. Raids as far east as the vicinity of Pittsburgh persuaded President Washington, on March 4, 1791, to summon St. Clair to Philadelphia. Hoping that St. Clair would succeed where General Joshua Harmar had failed the previous year, Washington then ordered him to establish a permanent military post at the head of the Maumee River in Central Ohio, where he could defend the territory against the Miami and Shawnee Indians. Both of these tribes were supported and supplied by the British who maintained posts at Detroit and Sandusky, which they used to harass Americans. (The British would hold on to these forts as bargaining chips until 1796.)

On September 17, St. Clair and an amateur army of about 1,400 ill-prepared and poorly equipped soldiers were soundly defeated in what would later become the state of Indiana by a combined force of 1,000 Miami and Shawnee Indians, who slaughtered more than 600 of his soldiers and at least fifty-six women who accompanied the army to cook, wash, and otherwise provide services for the troops. This defeat, the worst in the nation's long history of wars with Native Americans, left the United States with a total army of just 300 men, and the Pennsylvania frontier undefended.

St. Clair continued on as governor of the Northwest Territory, but Washington, having lost confidence in him, sent another expedition under the command of General Anthony Wayne. After supplying his troops at Fort Lafayette in Pittsburgh, Wayne's forces moved west via Cincinnati and the Miami Valley. In August, 1794, defeated the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and, two months later, established Fort Wayne in the present state of Indiana.

Fort Lafayette in Pittsburgh, Wayne's forces moved west via Cincinnati and the Miami Valley. In August, 1794, defeated the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and, two months later, established Fort Wayne in the present state of Indiana.

In 1802 President Thomas Jefferson removed St. Clair as governor of the Northwest Territory for his opposition to Ohio statehood. A Federalist, St. Clair had experienced difficulty governing the numerous Jeffersonians who had migrated north from Virginia and had no desire to add another state to the new president's increasing majority. St. Clair returned to his home at Chestnut Ridge near Youngstown PA, where he died in 1818.

As a leading citizen of the region and judge in Westmoreland County (formed in 1773), St. Clair negotiated some failed treaties with the Indians of the Ohio Valley and tried, with equal lack of success, to evict Virginians who also claimed what is now western Pennsylvania for their state. When the War for Independence broke out, St. Clair headed east, and soon rose to the rank of major general.

In 1777 his failure to fortify Mt. Defiance enabled the British under General John Burgoyne to take New York's Fort Ticonderoga and resulted in his own court-martial. Cleared of the charges he resigned from the service. In the meanwhile, he had staunchly opposed the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, which vested nearly all power in the state assembly. After the war, he helped found the Society of Cincinnati, where revolutionary officers and their descendants could celebrate their achievements, and served as a Pennsylvania delegate to Congress, and as its President from 1785 to 1787.

At the end of the American Revolution, Great Britain had ceded a vast area to the United States called the Northwest Territories: a region that stretched from Pennsylvania's western border to what is now the state of Minnesota. The United States wanted white Americans to populate the area to counter British, Spanish, and Native American claims to the region. And it could speed settlement by using some of those lands to compensate unpaid veterans and people who had loaned the government money during the war. But the states disputed ownership of millions of acres west of the Appalachians. The territory raised some daunting questions. How should the land be distributed or sold? Who should govern the settlements of independent-minded frontiersmen and their families? Should they be incorporated into existing states? Remain territories in which residents had only partial rights? If added to the union as new states, under what terms should they be admitted?

Justly criticized for its impotence in foreign and economic affairs, the Confederation government was remarkably successful in sorting things out in the west. It convinced the states to give up their claims to the western lands, and voided the overlapping individual and company land claims they had authorized in the region. Virginia's cession of land to Pennsylvania was especially important, because Virginia insisted Congress void all private, previous claims to western lands. It transferred what little remained of the United States army to the frontier in the hopes of taking actual possession of the land from the Indians.

In 1785, the Confederation government passed the Land Ordinance which provided for the survey of newly incorporated lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which established a system of government for the region and defined the process for the creation and admission of new states that we still follow today.

As a western Pennsylvanian who had already negotiated with Indians in the Ohio Valley, St. Clair was Congress's logical choice to be the Northwest Territories" first governor. Although later he would regard himself as "a poor devil banished to another planet," he at first welcomed the post in the hope of recovering the fortune that he had lost during the American Revolution.

St. Clair's first problem was that the Ohio Valley Indians had repudiated treaties negotiated by some of them - illegitimately, many claimed - that gave away much of the territory. Raids as far east as the vicinity of Pittsburgh persuaded President Washington, on March 4, 1791, to summon St. Clair to Philadelphia. Hoping that St. Clair would succeed where General Joshua Harmar had failed the previous year, Washington then ordered him to establish a permanent military post at the head of the Maumee River in Central Ohio, where he could defend the territory against the Miami and Shawnee Indians. Both of these tribes were supported and supplied by the British who maintained posts at Detroit and Sandusky, which they used to harass Americans. (The British would hold on to these forts as bargaining chips until 1796.)

On September 17, St. Clair and an amateur army of about 1,400 ill-prepared and poorly equipped soldiers were soundly defeated in what would later become the state of Indiana by a combined force of 1,000 Miami and Shawnee Indians, who slaughtered more than 600 of his soldiers and at least fifty-six women who accompanied the army to cook, wash, and otherwise provide services for the troops. This defeat, the worst in the nation's long history of wars with Native Americans, left the United States with a total army of just 300 men, and the Pennsylvania frontier undefended.

St. Clair continued on as governor of the Northwest Territory, but Washington, having lost confidence in him, sent another expedition under the command of General Anthony Wayne. After supplying his troops at

In 1802 President Thomas Jefferson removed St. Clair as governor of the Northwest Territory for his opposition to Ohio statehood. A Federalist, St. Clair had experienced difficulty governing the numerous Jeffersonians who had migrated north from Virginia and had no desire to add another state to the new president's increasing majority. St. Clair returned to his home at Chestnut Ridge near Youngstown PA, where he died in 1818.