![header=[Marker Text] body=[This was the nation's first major toll road, built by a private company incorporated 1792 by the state legislature. Completed two years later and praised as the finest highway of its day, the stone-and-gravel turnpike stretched 62 miles. The 35th milestone out of Philadelphia was placed here. Early in the 20th century, this road was acquired by the state; it became part of the transcontinental Lincoln Highway and U.S. 30.] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-28D-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h9f4-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road [New Nation]

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Chester

Marker Location:

Business US 30 at Veterans Drive just E of Coatesville

Dedication Date:

November 20, 1999

Behind the Marker

As early as 1700, the Pennsylvania legislature authorized the building of "king's highways" at the colony's expense that were to be fifty feet wide. The first, completed in 1706, connected Philadelphia and Chester. The second, which is now route 611, built in 1711, went north from Philadelphia to New Hope, then extended to Easton in 1722.

Pennsylvanians further west, however, lacked adequate transportation. In 1731 the citizens of the new city and county of Lancaster petitioned for a road as they did "not have the conveniencey of any navigable water to bring the produce of the laborers to Philadelphia." Thus their town required "suitable roads for carriages to pass." Two years later, the colony approved funding for what, when finished in 1741,became known as the Great Conestoga Road. It enabled the large Conestoga wagons, invented in Pennsylvania, to convey immigrants and their belongings west, and farmers, lumbermen, and iron makers to bring their products east.

With the French and Indian War and the American Revolution occupying Pennsylvanians for much of the next forty years, the Conestoga Road fell into disrepair. In 1786, residents of Lancaster petitioned the state legislature for an improved road to the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia. This petition coincided with the return of the Republicans to power in the state: their leaders, Robert Morris, Thomas Willing,

Robert Morris, Thomas Willing,  James Wilson, and William Bingham were committed to the state's economic development.

James Wilson, and William Bingham were committed to the state's economic development.

The Assembly, still coping with post-war economic hardship and distracted by the latter stages of the "internal revolution" between factions over the radical constitution of 1776, was in no position to address the request. But in 1791, after the conservatives had triumphed and adopted a new constitution, support for the project increased. Governor Thomas Mifflin recommended the idea to the new bicameral legislature, which decided that the cost of a graded gravel road was beyond the means of the state. But it did suggest that if a private company could be chartered and incorporated, and allowed to charge tolls, road construction could be funded in part by tolls collected after its completion.

Thomas Mifflin recommended the idea to the new bicameral legislature, which decided that the cost of a graded gravel road was beyond the means of the state. But it did suggest that if a private company could be chartered and incorporated, and allowed to charge tolls, road construction could be funded in part by tolls collected after its completion.

The legislature passed a bill for this purpose in 1792. That June, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company's commissioners opened a subscription for stock shares. The stock soon proved so popular that one observer coined the prophetic phrase "Turnpike Rage" to describe the frantic demand for shares. "Everything is now turned into Speculation," he said. "The quiet Quakers, who attended for the purpose of joining in the Subscription, and encouraging the road, finding such an uproar, withdrew." There were similar disorders at Lancaster, and in the end, shares had to be allocated by lottery to would-be subscribers.

The speculative mania carried over to the chartering of two canal companies: one to connect the Schuylkill and Susquehanna in central Pennsylvania and the other to connect the Delaware River with the Schuylkill at Norristown. But by 1794, despite spending $440,000, the companies had only managed to build fifteen miles of canals and several locks before they ran out of money. Work stopped on these projects until the Schuylkill Navigation Company and Union Canal Companies resumed the work in 1815.

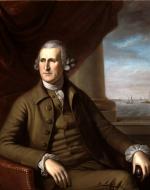

Turnpike construction proved much more successful than the canals. William Bingham, a prominent Philadelphia merchant who became a major land speculator after the Revolution, was elected president of the turnpike company. Despite other interests - he was a United States Senator and business partner of Robert Morris and Bank of the United States president Thomas Willing - he carefully supervised the construction of the project. Work on the road began early in 1793 and the highway was opened - if still partially incomplete - by late 1794. It cost $465,000 to connect Philadelphia with Lancaster, sixty-five miles to the west.

Shortly thereafter, the Lancaster and Susquehanna Company built another turnpike connecting Lancaster with the Susquehanna at Columbia. This proved especially useful after 1797, when the Conewago Canal Company built a short canal on the Susquehanna that circumvented the rapids and rocks at Conewago. By permitting relatively easy access from the Susquehanna to Philadelphia the new transportation system won commerce from central Pennsylvania that would otherwise have gone down the Susquehanna River to Baltimore.

During the early years of its existence, the state frequently amended the turnpike's charter to increase its profits, provide for the most convenient route, address the concerns of residents along its proposed route, and permit the company to fine toll evaders. The company erected scales at toll gates to "ascertain... the burden" of wagons, cattle, and carriages. The company was also authorized to "enter upon lands," or in other words to exercise a kind of eminent domain to lay out and operate the road. Despite the nine tolls along its route, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike cut farmers' transportation costs by two-thirds, and increased the speed and volume of commerce in southeastern Pennsylvania.

To learn more about the Turnpike's impact on Pennsylvania agriculture, click here.

click here.

Pennsylvanians further west, however, lacked adequate transportation. In 1731 the citizens of the new city and county of Lancaster petitioned for a road as they did "not have the conveniencey of any navigable water to bring the produce of the laborers to Philadelphia." Thus their town required "suitable roads for carriages to pass." Two years later, the colony approved funding for what, when finished in 1741,became known as the Great Conestoga Road. It enabled the large Conestoga wagons, invented in Pennsylvania, to convey immigrants and their belongings west, and farmers, lumbermen, and iron makers to bring their products east.

With the French and Indian War and the American Revolution occupying Pennsylvanians for much of the next forty years, the Conestoga Road fell into disrepair. In 1786, residents of Lancaster petitioned the state legislature for an improved road to the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia. This petition coincided with the return of the Republicans to power in the state: their leaders,

The Assembly, still coping with post-war economic hardship and distracted by the latter stages of the "internal revolution" between factions over the radical constitution of 1776, was in no position to address the request. But in 1791, after the conservatives had triumphed and adopted a new constitution, support for the project increased. Governor

The legislature passed a bill for this purpose in 1792. That June, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company's commissioners opened a subscription for stock shares. The stock soon proved so popular that one observer coined the prophetic phrase "Turnpike Rage" to describe the frantic demand for shares. "Everything is now turned into Speculation," he said. "The quiet Quakers, who attended for the purpose of joining in the Subscription, and encouraging the road, finding such an uproar, withdrew." There were similar disorders at Lancaster, and in the end, shares had to be allocated by lottery to would-be subscribers.

The speculative mania carried over to the chartering of two canal companies: one to connect the Schuylkill and Susquehanna in central Pennsylvania and the other to connect the Delaware River with the Schuylkill at Norristown. But by 1794, despite spending $440,000, the companies had only managed to build fifteen miles of canals and several locks before they ran out of money. Work stopped on these projects until the Schuylkill Navigation Company and Union Canal Companies resumed the work in 1815.

Turnpike construction proved much more successful than the canals. William Bingham, a prominent Philadelphia merchant who became a major land speculator after the Revolution, was elected president of the turnpike company. Despite other interests - he was a United States Senator and business partner of Robert Morris and Bank of the United States president Thomas Willing - he carefully supervised the construction of the project. Work on the road began early in 1793 and the highway was opened - if still partially incomplete - by late 1794. It cost $465,000 to connect Philadelphia with Lancaster, sixty-five miles to the west.

Shortly thereafter, the Lancaster and Susquehanna Company built another turnpike connecting Lancaster with the Susquehanna at Columbia. This proved especially useful after 1797, when the Conewago Canal Company built a short canal on the Susquehanna that circumvented the rapids and rocks at Conewago. By permitting relatively easy access from the Susquehanna to Philadelphia the new transportation system won commerce from central Pennsylvania that would otherwise have gone down the Susquehanna River to Baltimore.

During the early years of its existence, the state frequently amended the turnpike's charter to increase its profits, provide for the most convenient route, address the concerns of residents along its proposed route, and permit the company to fine toll evaders. The company erected scales at toll gates to "ascertain... the burden" of wagons, cattle, and carriages. The company was also authorized to "enter upon lands," or in other words to exercise a kind of eminent domain to lay out and operate the road. Despite the nine tolls along its route, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike cut farmers' transportation costs by two-thirds, and increased the speed and volume of commerce in southeastern Pennsylvania.

To learn more about the Turnpike's impact on Pennsylvania agriculture,