![header=[Marker Text] body=[Here was Pennsylvania's only training camp for African American soldiers – and the largest of the 18 in the nation – during the Civil War. Comprising over 10,000 men, 11 regiments of U.S. Colored Troops were trained here: the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 22nd, 24th, 25th, 32nd, 41st, 43rd, 45th and 127th. Recruits first arrived on June 26, 1863; many were to fight in Virginia, South Carolina, Florida and elsewhere. The camp closed August 14, 1865. ] sign](kora/files/1/10/1-A-124-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a4o5-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Camp William Penn

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Montgomery

Marker Location:

7322 Sycamore Ave, LaMott

Dedication Date:

May 15, 1999

Behind the Marker

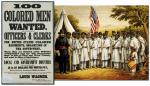

In 1865, Harriet Tubman, the legendary Underground Railroad operator, gave a stirring speech to one of the last detachments of black soldiers trained at Camp William Penn. Like her, many of the men were former slaves, determined to help end slavery. And like Tubman, these young soldiers were prepared to risk either death or enslavement to participate in the cause of freedom.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, not only pledged to free Rebel-owned slaves, but also offered positions in the Union armed forces to any African Americans of "suitable condition." Blacks had served in previous American military conflicts, most notably during the Revolution, but President Lincoln's decision to encourage African American enlistment during the Civil War marked a great departure.

Approximately 180,000 African Americans served in the Union army and more than 15,000 joined the Union navy. The recruits trained at Camp William Penn served in the army. The camp was situated on the outskirts of Philadelphia on land previously owned by the family of well-known Quaker abolitionist Lucretia Mott. She recalled that "the barracks make a show from our back window."

Lucretia Mott. She recalled that "the barracks make a show from our back window."

Louis Wagner, Camp William Penn's white commander, fought to protect his men from discrimination. He ignored complaints from city officials about parading his men through Philadelphia and insisted that local streetcars desegregate seating for his troops.

Wagner was less successful fighting discrimination within the army itself. For over a year, black troops received less pay than white soldiers, and, with only a few exceptions, they were not allowed to have black officers. Most white officers in charge often had little respect for their African American troops, embodying the racist attitudes of the era.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, not only pledged to free Rebel-owned slaves, but also offered positions in the Union armed forces to any African Americans of "suitable condition." Blacks had served in previous American military conflicts, most notably during the Revolution, but President Lincoln's decision to encourage African American enlistment during the Civil War marked a great departure.

Approximately 180,000 African Americans served in the Union army and more than 15,000 joined the Union navy. The recruits trained at Camp William Penn served in the army. The camp was situated on the outskirts of Philadelphia on land previously owned by the family of well-known Quaker abolitionist

Louis Wagner, Camp William Penn's white commander, fought to protect his men from discrimination. He ignored complaints from city officials about parading his men through Philadelphia and insisted that local streetcars desegregate seating for his troops.

Wagner was less successful fighting discrimination within the army itself. For over a year, black troops received less pay than white soldiers, and, with only a few exceptions, they were not allowed to have black officers. Most white officers in charge often had little respect for their African American troops, embodying the racist attitudes of the era.

Beyond the Marker