Chapter One: Turning Stones to Diamonds

In 1812, a Colonel George Shoemaker appeared in Philadelphia with nine loads of anthracite for sale. He had made an arduous and expensive journey from Pottsville, carting his cargo along nearly impassable roads. Unfortunately, after his new customers tried unsuccessfully to light the anthracite in their fireplaces, they gathered into an angry mob that practically ran Shoemaker out of town, calling him a "swindler and an imposter, for attempting to impose stone on them for coal." Escaping their threats, he managed to sell a couple of loads and gave away the rest.

By the early 19th century, entrepreneurs like Colonel Shoemaker had come to believe that the hard, carbon-rich anthracite of northeastern Pennsylvania should be able to heat homes and fire furnaces. Before they could make their fortunes from this plentiful resource, however, they had to discover practical ways to ignite the clean, long-burning coal in ways suitable for homes and industry. They also faced other daunting problems: how to win over skeptical customers and how to transport the anthracite from the mountainous "wilds" of Schuylkill, Luzerne and Lackawanna counties to American cities on the east coast. Despite these challenges, adventuresome pioneer entrepreneurs had, within one generation, tapped the coal fields and conjured eastern markets, turning the stones into diamonds.

The pressure to figure out the anthracite puzzle had been building since the 1780s and 1790s, when reports about discoveries of the "stone-coal" grew more frequent in the Lehigh and Wyoming Valleys. One Necho Allen purportedly "discovered" anthracite in Schuylkill County when his campfire burned exceedingly bright and hot one night: he had lit it on some exposed anthracite. In present day Carbon County, a hunter named Philip Ginter was desperately trying to feed his family when, according to legend, he "stumbled" onto a chunk of anthracite. The truth behind this folktale is a bit more complicated, but the indisputable result of his "discovery" was the formation of the first anthracite company, a small firm that later became the giant Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

Philip Ginter was desperately trying to feed his family when, according to legend, he "stumbled" onto a chunk of anthracite. The truth behind this folktale is a bit more complicated, but the indisputable result of his "discovery" was the formation of the first anthracite company, a small firm that later became the giant Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

To make anthracite practical for home heating, Jesse Fell, a local businessman and civic leader from Wilkes-Barre, experimented with burning anthracite in an "L" shaped open-air grate. His breakthrough in 1808 allowed consumers to safely place anthracite coals in their fireplaces. Although other men had experimented with this idea before Fell, his solution took hold due to the marketing efforts of coal operators Abijah and John Smith. Their

Jesse Fell, a local businessman and civic leader from Wilkes-Barre, experimented with burning anthracite in an "L" shaped open-air grate. His breakthrough in 1808 allowed consumers to safely place anthracite coals in their fireplaces. Although other men had experimented with this idea before Fell, his solution took hold due to the marketing efforts of coal operators Abijah and John Smith. Their  Abijah Smith and Co. used Fell's grate to convince skeptical farmers along the Susquehanna River of the utility of anthracite. Their success proves the revolutionary significance of this simple technology. In 1807, the Smiths had to leave unsold anthracite by the side of the river, because nobody wanted the product. One year later, after Fell's advance, they sold out their load and effectively launched the first successful anthracite firm in the nation.

Abijah Smith and Co. used Fell's grate to convince skeptical farmers along the Susquehanna River of the utility of anthracite. Their success proves the revolutionary significance of this simple technology. In 1807, the Smiths had to leave unsold anthracite by the side of the river, because nobody wanted the product. One year later, after Fell's advance, they sold out their load and effectively launched the first successful anthracite firm in the nation.

Jacob Cist, anthracite's greatest promoter, also set his mind to overcoming the reluctance of potential buyers of anthracite. Like the Smith brothers, he demonstrated to customers how to burn anthracite, wrote articles and pamphlets about how cleanly it burned, and gathered testimonials to further convince wary Philadelphians. Cist's efforts to market his Summit Hill coal, mined near Mauch Chunk, did increase demand, especially when the War of 1812 disrupted the supply of imported coal and iron from Britain. The fuel crisis that hit Philadelphia during the cold winter of 1814 might have led to further gains in anthracite usage, but Cist was unable to capitalize on this opportunity due to inadequate transportation routes from northeastern Pennsylvania.

For the men employed by Shoemaker, the Smiths, and Cist during these early years, mining was an aboveground endeavor. The first generation of miners picked and loaded coal from exposed "veins" and where the coal outcropped on a hillside. When pits reached the depth of 40 or 50 feet, water accumulation often prohibited further coal extraction. Next came drift mines, which used horizontal entries driven slightly upward into hillsides to allow for drainage. Picks, shovels and wheelbarrows were the primary tools used in this backbreaking work. Coal was then loaded onto wagons and driven miles to the nearest river, over rutted and muddy roads. A revolution in transportation would be necessary in order to make anthracite mining a major industry.

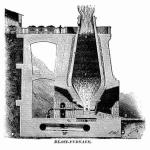

The problem of integrating anthracite into the industrial process proved just as difficult. Experiments in Europe and America sought alternatives to iron made with charcoal as forests disappeared and the distances between available timber supplies and markets grew ever greater. The Journal of the Franklin Institute and other publications circulated news of numerous experiments using anthracite to smelt iron. Not until the 1830s did a group of innovators figure out how to create a "hot-blast" process that would generate heat intense enough to burn anthracite in commercial furnaces and produce quality pig iron.

Many Pennsylvanians deserve a share of the credit for the revolutionary idea. One is Frederick W. Geissenhainer, a multi-tasking Lutheran minister who first applied his patented ideas at the Valley Furnace in Pottsville in 1836. Soon after, entrepreneur

Valley Furnace in Pottsville in 1836. Soon after, entrepreneur  Burd Patterson helped expand the anthracite iron experiments at his Pioneer Furnace in Pottsville. What Geissenheiner and Patterson lacked, however, was significant capital backing.

Burd Patterson helped expand the anthracite iron experiments at his Pioneer Furnace in Pottsville. What Geissenheiner and Patterson lacked, however, was significant capital backing.

Connections were key in the overall development of anthracite's utility, in both the figurative and literal senses. Two important anthracite pioneers were Erskine Hazard and Josiah White, Quaker businessmen from Philadelphia. They had purchased a load of coal from Col. Shoemaker in 1812 for their wire mill on the falls of the Schuylkill River. Sensing opportunity, they leased Jacob Cist's mine at Summit Hill in 1818, and formed the Lehigh Coal Company. In the same year, they used their connections within the Pennsylvania state government to gain an exclusive, thirty-six-year long charter to improve the navigability of the Lehigh River, which would be vital if they were to succeed where Cist had failed. Forming the Lehigh Navigation Company, they soon began work on their Lehigh Canal, which ran from Mauch Chunk to Easton and then to the Delaware River, providing their coal company with dependable transportation to the Philadelphia market. During the 1820s and 1830s, they sent thousands of tons of coal to market, creating the powerful Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

Lehigh Canal, which ran from Mauch Chunk to Easton and then to the Delaware River, providing their coal company with dependable transportation to the Philadelphia market. During the 1820s and 1830s, they sent thousands of tons of coal to market, creating the powerful Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

In 1839, Hazard traveled to Wales to hire David Thomas for the newly incorporated

David Thomas for the newly incorporated  Lehigh Crane Iron Works, on the banks of the Lehigh River. Thomas, an ironmaster from Wales, was able to combine his technical expertise with the large amounts of capital available from his employers and succeeded where Geissenhainer and Patterson had fallen short. Familiar with the "hot-blast" process of heating air before sending it into the furnace, Thomas successfully fired his furnace on July 4, 1840 at

Lehigh Crane Iron Works, on the banks of the Lehigh River. Thomas, an ironmaster from Wales, was able to combine his technical expertise with the large amounts of capital available from his employers and succeeded where Geissenhainer and Patterson had fallen short. Familiar with the "hot-blast" process of heating air before sending it into the furnace, Thomas successfully fired his furnace on July 4, 1840 at  Biery's Port in present-day Catasauqua and became known as the "Father of the anthracite iron industry."

Biery's Port in present-day Catasauqua and became known as the "Father of the anthracite iron industry."

The first fully operational and commercially successful anthracite iron furnace in America, the Lehigh Crane Iron Works was the final piece in one of the first powerful monopolies of the anthracite fields: a set of related corporations owning thousands of acres of prime coal land, controlling inland waterways to the East, and developing related industrial production using anthracite as fuel.

By the early 19th century, entrepreneurs like Colonel Shoemaker had come to believe that the hard, carbon-rich anthracite of northeastern Pennsylvania should be able to heat homes and fire furnaces. Before they could make their fortunes from this plentiful resource, however, they had to discover practical ways to ignite the clean, long-burning coal in ways suitable for homes and industry. They also faced other daunting problems: how to win over skeptical customers and how to transport the anthracite from the mountainous "wilds" of Schuylkill, Luzerne and Lackawanna counties to American cities on the east coast. Despite these challenges, adventuresome pioneer entrepreneurs had, within one generation, tapped the coal fields and conjured eastern markets, turning the stones into diamonds.

The pressure to figure out the anthracite puzzle had been building since the 1780s and 1790s, when reports about discoveries of the "stone-coal" grew more frequent in the Lehigh and Wyoming Valleys. One Necho Allen purportedly "discovered" anthracite in Schuylkill County when his campfire burned exceedingly bright and hot one night: he had lit it on some exposed anthracite. In present day Carbon County, a hunter named

To make anthracite practical for home heating,

Jacob Cist, anthracite's greatest promoter, also set his mind to overcoming the reluctance of potential buyers of anthracite. Like the Smith brothers, he demonstrated to customers how to burn anthracite, wrote articles and pamphlets about how cleanly it burned, and gathered testimonials to further convince wary Philadelphians. Cist's efforts to market his Summit Hill coal, mined near Mauch Chunk, did increase demand, especially when the War of 1812 disrupted the supply of imported coal and iron from Britain. The fuel crisis that hit Philadelphia during the cold winter of 1814 might have led to further gains in anthracite usage, but Cist was unable to capitalize on this opportunity due to inadequate transportation routes from northeastern Pennsylvania.

For the men employed by Shoemaker, the Smiths, and Cist during these early years, mining was an aboveground endeavor. The first generation of miners picked and loaded coal from exposed "veins" and where the coal outcropped on a hillside. When pits reached the depth of 40 or 50 feet, water accumulation often prohibited further coal extraction. Next came drift mines, which used horizontal entries driven slightly upward into hillsides to allow for drainage. Picks, shovels and wheelbarrows were the primary tools used in this backbreaking work. Coal was then loaded onto wagons and driven miles to the nearest river, over rutted and muddy roads. A revolution in transportation would be necessary in order to make anthracite mining a major industry.

The problem of integrating anthracite into the industrial process proved just as difficult. Experiments in Europe and America sought alternatives to iron made with charcoal as forests disappeared and the distances between available timber supplies and markets grew ever greater. The Journal of the Franklin Institute and other publications circulated news of numerous experiments using anthracite to smelt iron. Not until the 1830s did a group of innovators figure out how to create a "hot-blast" process that would generate heat intense enough to burn anthracite in commercial furnaces and produce quality pig iron.

Many Pennsylvanians deserve a share of the credit for the revolutionary idea. One is Frederick W. Geissenhainer, a multi-tasking Lutheran minister who first applied his patented ideas at the

Connections were key in the overall development of anthracite's utility, in both the figurative and literal senses. Two important anthracite pioneers were Erskine Hazard and Josiah White, Quaker businessmen from Philadelphia. They had purchased a load of coal from Col. Shoemaker in 1812 for their wire mill on the falls of the Schuylkill River. Sensing opportunity, they leased Jacob Cist's mine at Summit Hill in 1818, and formed the Lehigh Coal Company. In the same year, they used their connections within the Pennsylvania state government to gain an exclusive, thirty-six-year long charter to improve the navigability of the Lehigh River, which would be vital if they were to succeed where Cist had failed. Forming the Lehigh Navigation Company, they soon began work on their

In 1839, Hazard traveled to Wales to hire

The first fully operational and commercially successful anthracite iron furnace in America, the Lehigh Crane Iron Works was the final piece in one of the first powerful monopolies of the anthracite fields: a set of related corporations owning thousands of acres of prime coal land, controlling inland waterways to the East, and developing related industrial production using anthracite as fuel.