Chapter Three: Wartime Mobilization

On the day of the Civil War's first major battle, a volunteer regiment from Pennsylvania learned that their three-month tour-of-duty had expired. So they dropped out of the march toward Bull Run Creek in northern Virginia and caught a train back to Harrisburg. Union forces subsequently endured an embarrassing defeat and the Pennsylvania troops who abandoned their comrades-in-arms were widely criticized.

Things got worse for the men once they returned to the state capital. To receive their final payment, the temporary soldiers had to wait around for the overwhelmed army bureaucrats to process their final paperwork.

It was late July 1861, and Harrisburg was soon filling up with hungry, tired, angry young men with nowhere to sleep and little to eat. For a while, they were content to fight with each other, but soon they organized themselves against the army officials in charge.

A group of men stole a cannon, placed it on a low wagon, and wheeled it to the city's main hotel where the son of Secretary of War Simon Cameron was holed up, trying to sort out the mess. The rioters vowed to blow up the building. Their threat was disturbing, but was not taken too seriously because they failed to secure any ammunition.

Simon Cameron was holed up, trying to sort out the mess. The rioters vowed to blow up the building. Their threat was disturbing, but was not taken too seriously because they failed to secure any ammunition.

Eventually, tempers cooled, men got paid, and Harrisburg returned to normal, but it is not easy to explain such a story. How could loyal troops just drop out of service before a major battle? How could military officials be so unprepared for processing their departure? There are many answers, but one overriding explanation. Nobody expected a conflict of such overwhelming magnitude. The mobilization of men and resources for the Civil War was the greatest undertaking in the history of American government up until that point. It did not go smoothly.

More remarkable than the short-term failures, however, were the long-term successes. Ultimately, state and federal officials figured out how to make the system work – never perfectly, but eventually with surprising efficiency. At the start of the Civil War, there was a mere 16,000 officers and men enlisted in the United States Army.

Facing this shortage in manpower, just days after the firing on Fort Sumter President Lincoln issued a call to the States to raise militia units to put down the insurrection. Pennsylvania responded quickly, offering twenty-five regiments. By July, Congress authorized the creation of a volunteer army of 500,000, but individual states remained responsible for enlisting and outfitting their soldiers.

In Pennsylvania, two determined overworked officials, Governor Andrew Curtin and Secretary of the Commonwealth

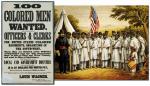

Andrew Curtin and Secretary of the Commonwealth  Eli Slifer, organized the mobilization effort. They pleaded, cajoled and argued with various recruitment officials - and each destroyed his health in the process - but somehow they both managed to survive the war and earn reputations for loyal devotion to the Union cause. Ultimately, nearly 350,000 Pennsylvanians served in the Union Forces. Of these, an estimated 8,600 were African American volunteers.

Eli Slifer, organized the mobilization effort. They pleaded, cajoled and argued with various recruitment officials - and each destroyed his health in the process - but somehow they both managed to survive the war and earn reputations for loyal devotion to the Union cause. Ultimately, nearly 350,000 Pennsylvanians served in the Union Forces. Of these, an estimated 8,600 were African American volunteers.

Camp Curtin, the state's principal military training facility, was named after the hard-working governor. Over 80 percent of the men who enlisted in the war effort from Pennsylvania passed through this former agricultural fairground, situated on the outskirts of Harrisburg.

Camp Curtin, the state's principal military training facility, was named after the hard-working governor. Over 80 percent of the men who enlisted in the war effort from Pennsylvania passed through this former agricultural fairground, situated on the outskirts of Harrisburg.

Despite the fact that Camp Curtin and other facilities helped pour hundreds of thousands of new recruits into the Union army, there was growing concern among northern political leaders over an impending manpower shortage.

To help remedy the problem, Andrew Curtin called for an emergency meeting of northern governors in early autumn 1862. Fourteen state executives participated in the Altoona Conference, held on September 24, 1862 at the

Altoona Conference, held on September 24, 1862 at the  Logan House in the bustling railroad junction. They had a candid discussion that helped cement support behind President Lincoln's war policies, and his recently announced decision to offer emancipation for Confederate-owned slaves.

Logan House in the bustling railroad junction. They had a candid discussion that helped cement support behind President Lincoln's war policies, and his recently announced decision to offer emancipation for Confederate-owned slaves.

The decision to embrace black freedom was controversial. Even Governor Curtin was skeptical about emancipation, but Lincoln considered it essential to winning the war. He had resisted endorsing emancipation for most of the war's first year, but by the summer of 1862, the pressure to strike at the heart of Southern interests had become too overwhelming.

Just a few days before the governors' conference, Lincoln announced his intentions to issue an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. He later claimed that "no human power" could subdue the rebellion "without using the Emancipation lever as I have done." For Lincoln and many others, the issue was military necessity as much as moral imperative. "Freedom has given us the control of 200,000 able bodied men, born & raised on southern soil," he stated earnestly in 1864.

Lincoln was slightly wrong on his figures, but absolutely correct about the value of African Americans to the Union cause. Historians now estimate that over 180,000 blacks, both freeborn northerners and freed southern slaves, ultimately served in the federal army, providing the critical difference in the final years of the conflict.

In Pennsylvania, black soldiers were trained at Camp William Penn in Montgomery County. Most served under white officers and received less pay than their white counterparts, but their desire to fight for the cause earned respect from many previously skeptical whites, including President Lincoln.

Camp William Penn in Montgomery County. Most served under white officers and received less pay than their white counterparts, but their desire to fight for the cause earned respect from many previously skeptical whites, including President Lincoln.  Martin Delany, a leading black intellectual and activist from Pittsburgh, drew particular praise from Lincoln. Delany earned his commission as the first African American major in the U.S. army.

Martin Delany, a leading black intellectual and activist from Pittsburgh, drew particular praise from Lincoln. Delany earned his commission as the first African American major in the U.S. army.

Black soldiers helped alleviate the critical manpower shortage during the final two years of the war, but the War Department continued to seek ways to drum up more white enlistment. They provided bounties for volunteers, allowed paid substitutes for draftees, and even created a category of soldiers called "representative recruits" who were supposed to be sponsored by those who were not otherwise eligible to serve.

President Lincoln tried to encourage this process, naming East Stroudsburg native John Staples as his designated recruit. He met the 19-year-old and his father at the White House in 1864, expressing the hope that he would be "one of the fortunate ones." Ironically, the young Pennsylvanian survived the war even though his sponsor did not.

John Staples as his designated recruit. He met the 19-year-old and his father at the White House in 1864, expressing the hope that he would be "one of the fortunate ones." Ironically, the young Pennsylvanian survived the war even though his sponsor did not.

Things got worse for the men once they returned to the state capital. To receive their final payment, the temporary soldiers had to wait around for the overwhelmed army bureaucrats to process their final paperwork.

It was late July 1861, and Harrisburg was soon filling up with hungry, tired, angry young men with nowhere to sleep and little to eat. For a while, they were content to fight with each other, but soon they organized themselves against the army officials in charge.

A group of men stole a cannon, placed it on a low wagon, and wheeled it to the city's main hotel where the son of Secretary of War

Eventually, tempers cooled, men got paid, and Harrisburg returned to normal, but it is not easy to explain such a story. How could loyal troops just drop out of service before a major battle? How could military officials be so unprepared for processing their departure? There are many answers, but one overriding explanation. Nobody expected a conflict of such overwhelming magnitude. The mobilization of men and resources for the Civil War was the greatest undertaking in the history of American government up until that point. It did not go smoothly.

More remarkable than the short-term failures, however, were the long-term successes. Ultimately, state and federal officials figured out how to make the system work – never perfectly, but eventually with surprising efficiency. At the start of the Civil War, there was a mere 16,000 officers and men enlisted in the United States Army.

Facing this shortage in manpower, just days after the firing on Fort Sumter President Lincoln issued a call to the States to raise militia units to put down the insurrection. Pennsylvania responded quickly, offering twenty-five regiments. By July, Congress authorized the creation of a volunteer army of 500,000, but individual states remained responsible for enlisting and outfitting their soldiers.

In Pennsylvania, two determined overworked officials, Governor

Despite the fact that Camp Curtin and other facilities helped pour hundreds of thousands of new recruits into the Union army, there was growing concern among northern political leaders over an impending manpower shortage.

To help remedy the problem, Andrew Curtin called for an emergency meeting of northern governors in early autumn 1862. Fourteen state executives participated in the

The decision to embrace black freedom was controversial. Even Governor Curtin was skeptical about emancipation, but Lincoln considered it essential to winning the war. He had resisted endorsing emancipation for most of the war's first year, but by the summer of 1862, the pressure to strike at the heart of Southern interests had become too overwhelming.

Just a few days before the governors' conference, Lincoln announced his intentions to issue an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. He later claimed that "no human power" could subdue the rebellion "without using the Emancipation lever as I have done." For Lincoln and many others, the issue was military necessity as much as moral imperative. "Freedom has given us the control of 200,000 able bodied men, born & raised on southern soil," he stated earnestly in 1864.

Lincoln was slightly wrong on his figures, but absolutely correct about the value of African Americans to the Union cause. Historians now estimate that over 180,000 blacks, both freeborn northerners and freed southern slaves, ultimately served in the federal army, providing the critical difference in the final years of the conflict.

In Pennsylvania, black soldiers were trained at

Black soldiers helped alleviate the critical manpower shortage during the final two years of the war, but the War Department continued to seek ways to drum up more white enlistment. They provided bounties for volunteers, allowed paid substitutes for draftees, and even created a category of soldiers called "representative recruits" who were supposed to be sponsored by those who were not otherwise eligible to serve.

President Lincoln tried to encourage this process, naming East Stroudsburg native