The Peopling of Pennsylvania: The Creation of a Multicultural Society

Migration and mobility, the ebb and flow of natives and newcomers and their continuous interactions over centuries fashioned Pennsylvania into a complex, pluralistic, and multicultural society. This diversity shaped the contours of historical experience and everyday life, laying a foundation for both mutual progress and turmoil. Over time, a patchwork quilt of ethnic and racial groups, with common dreams and unique cultural traditions, came to define the character of the Commonwealth and its citizenry. Equally significant, Pennsylvania became the staging ground for a sustained internal migration across the North American continent. There is something quintessentially American in the peopling of Pennsylvania and the world its many residents made together.

Stretching back more than 15,000 years, successive waves of newcomers brought their own distinctive customs and folkways into the region Englishmen would call Pennsylvania. For the first migrants, known as Indians or Native Americans, present-day political boundaries and place names meant nothing. Long before roads defined human mobility, these first settlers followed mountain valleys and rivers to traverse the interior of the Mid-Atlantic region. Even today, many of our roads follow the paths they first used.

Archeological evidence suggests that thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans and Africans, Native Americans established nomadic and then more permanent settlements in the Mid-Atlantic woodlands. Moving through the Delaware and Susquehanna River valleys and the western Ohio Country, these first "Pennsylvanians" hunted and planted, engaged in warfare, intermingled, and created economies of mutual exchange. By the late 1600s, Lenapes, Susquehannock, Nanticokes, Iroquois, and other tribal peoples had an established if sometimes unstable presence in the region.

Beginning in the 1630s, the Swedish and Dutch became the first Europeans to establish a presence in the Mid-Atlantic region, their small settlements dotting the area to the south and east of present-day Philadelphia. In 1682, they relinquished formal possession to William Penn. English by birth and a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers) by conviction, Penn imagined his new colony as a "Holy Experiment" committed to tolerance, freedom of conscience, and participatory governance. The Proprietor encouraged immigration as a solution for religious groups historically persecuted throughout the British Isles and much of Europe. Penn also promoted peaceful relations with Indians and all that makes for "safety and happiness."

Penn's promise, and the abundant land and resources of this "best poor man's country," sparked a great wave of European migration that flooded through Philadelphia, which quickly became a hub in Britain's far-flung trans-Atlantic empire, and across the hinterlands in the 1700s. With more than a quarter-million inhabitants by the eve of the American Revolution, Pennsylvania was the most diverse colony in British North America. Though officially English in its law and customs, Pennsylvania included large and culturally diverse settlements of Germans (about one-third the colony's population in 1776), Irish, Welsh, Ulster Scots (about one-quarter the colony's population), and other European groups.

On the eve of the American Revolution, close to 6,000 enslaved African Americans and a small population of free blacks also lived in the Commonwealth. Native Americans, however, were driven westward as a result of Europeans' growing numbers and two bitter and deadly wars: The French and Indian War, and the American Revolutionary War. By 1800 only a small Seneca reservation remained in the state.

Ethnic diversity corresponded to a new religious pluralism. Anglicans, Quakers and other dissenters from the Church of England, Evangelical Lutherans, Presbyterians, Moravians, German Reformed, Anabaptists like the Amish and Mennonites, Jews, and Catholics were among the many religious groups that populated Philadelphia and the outlying townships that stretched west across the Allegheny Mountains. By 1800, Pennsylvania had become of a land of cultural contrasts, with a spirited sense of local and community values that has continued to influence Commonwealth politics to the present day. Pennsylvania's diversity also contributed to periodic, and at times deadly conflicts.

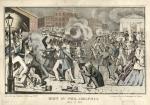

Between 1790 and 1860, a second great wave of European immigration coincided with the early industrial revolution, and a growing number of free blacks and runaway slaves escaped to Pennsylvania in their pursuit of freedom. Although substantial numbers of Irish came to Pennsylvania beginning in the late 1700s, a huge new wave of Irish flooded into Philadelphia and other northeastern port cities in the wake of the Potato Famine of the 1840s. Impoverished and Catholic, these Irish newcomers struggled to establish an economic foothold and stable social institutions amidst a rising tide of violent urban rioting and the political backlash of Protestant Nativists. In these same years, African Americans became targets for pent up social prejudices that boiled over on the eve of the Civil War.

During the Civil War, foreign immigration to Pennsylvania declined sharply. Even so, many African Americans, Germans, Irish and other groups sought to secure a greater degree of freedom and social acceptance by supporting the Union cause. Pennsylvanians played key roles as part of the Irish, or "Paddy," and German brigades, and the United States Colored Troops. Following the war, the industrial "Pennsylvania Empire" expanded at an unprecedented pace and an almost insatiable demand for labor in transportation, steel, mining, and other industries drew millions of newcomers to industrial towns and cities across the Commonwealth.

By 1890, southern and eastern European immigrants had replaced the earlier immigrants from western and northern Europe-Old verses New Immigrants, some called them-in the search for a stable and secure future in Pennsylvania. With families and sometimes entire villages following each other, the new immigrants included Italians, Poles, Russians, Hungarians, Czechs and Slovaks, Jews, Greeks, and a multitude of other groups different in language, culture, and identity.

On the eve of the First World War, close to 19 percent of the Commonwealth's population at more than 8 million was foreign-born, and a new and more diverse society was taking shape in Pennsylvania and across urban America. In Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Scranton, Steelton, Coatesville, and other towns across the Commonwealth, ethnically distinct immigrant settlements had formed in close proximity to "native" white neighborhoods. The resulting social interactions were often shaped by a clannishness based on mutual suspicion that disguised the common economic interests each group shared.

What made this mix potentially more volatile was the steady migration of southern blacks drawn by the hope of better jobs and social freedom beyond the Jim Crow South. Moving into Pennsylvania in large numbers between the 1890s and the 1950s-Pennsylvania's African American population would soar from 156,000 in 1900 to more than 1,000,000 in 1970-southern blacks, like earlier generations of migrants, shared the hope that Pennsylvania could offer to a better future for themselves and their descendants.

Anti-immigrant sentiments during the First World War resulted in new federal legislation that cut the great flow of immigration to the United States from a flood to a trickle from the early 1920s to the mid-1960s. In the half-century following the end of the Second World War, many of Pennsylvania's once formidable railroad, steel, mining, textile, and other industries collapsed, and "deindustrialization" exacted a tremendous social and human cost in communities across the Commonwealth. Changes in federal immigration policy after passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 unleashed yet another wave of immigration that has brought hundreds of thousands of newcomers from the Americas, Africa, and Asia into the Commonwealth, and millions to America. Pennsylvania, however, was no longer one of the favored destinations.

In 2008, just 5.3 percent of Pennsylvanians were foreign born: 665,000 of the state's 12,400,000 residents. (That year, by comparison, twelve states had a larger foreign-born population and twenty-nine states had a higher percentage of immigrants than the Commonwealth.) Thirty-seven percent had come from Asia, 27.1 percent from Europe, 28.5 percent from Latin America, 7.2 percent from Africa, 2.4 percent from North America (not including Mexico), and 0.5 percent from Oceania. (Compare this to 1930, when more than 72 percent of Pennsylvania's foreign-born residents had come from southern and eastern Europe.) This latest wave of immigrants tended to be older and better educated than earlier generations of newcomers; indeed, they were 10 percent more likely to have a college degree than native-born Americans over the age of twenty-five.

Although Pennsylvania's historical markers do an excellent documenting the experiences of successive generations of immigrants, these same markers have often neglected the achievements of millions of women who came to Pennsylvania. Single and married women, mothers and wives, domestic workers and those who entered Pennsylvania's vast industrial economy-their stories too are part the broad cloth of Pennsylvania history.

Despite shifting economic and social forces, Pennsylvania's newest immigrants have struggled to preserve their cultural heritage even as they embrace the economic and social possibilities that William Penn imagined centuries ago. Controversial incidents like Hazleton's passage of a local Illegal Immigration Relief Act in 2006, which attracted national attention, serve as a reminder of the persistence of anti-immigrant sentiments in Pennsylvania and across America. The ongoing historical drama of forging a complex multicultural society continues to be at the heart of the Pennsylvania experience in the new millennium.

Stretching back more than 15,000 years, successive waves of newcomers brought their own distinctive customs and folkways into the region Englishmen would call Pennsylvania. For the first migrants, known as Indians or Native Americans, present-day political boundaries and place names meant nothing. Long before roads defined human mobility, these first settlers followed mountain valleys and rivers to traverse the interior of the Mid-Atlantic region. Even today, many of our roads follow the paths they first used.

Archeological evidence suggests that thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans and Africans, Native Americans established nomadic and then more permanent settlements in the Mid-Atlantic woodlands. Moving through the Delaware and Susquehanna River valleys and the western Ohio Country, these first "Pennsylvanians" hunted and planted, engaged in warfare, intermingled, and created economies of mutual exchange. By the late 1600s, Lenapes, Susquehannock, Nanticokes, Iroquois, and other tribal peoples had an established if sometimes unstable presence in the region.

Beginning in the 1630s, the Swedish and Dutch became the first Europeans to establish a presence in the Mid-Atlantic region, their small settlements dotting the area to the south and east of present-day Philadelphia. In 1682, they relinquished formal possession to William Penn. English by birth and a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers) by conviction, Penn imagined his new colony as a "Holy Experiment" committed to tolerance, freedom of conscience, and participatory governance. The Proprietor encouraged immigration as a solution for religious groups historically persecuted throughout the British Isles and much of Europe. Penn also promoted peaceful relations with Indians and all that makes for "safety and happiness."

Penn's promise, and the abundant land and resources of this "best poor man's country," sparked a great wave of European migration that flooded through Philadelphia, which quickly became a hub in Britain's far-flung trans-Atlantic empire, and across the hinterlands in the 1700s. With more than a quarter-million inhabitants by the eve of the American Revolution, Pennsylvania was the most diverse colony in British North America. Though officially English in its law and customs, Pennsylvania included large and culturally diverse settlements of Germans (about one-third the colony's population in 1776), Irish, Welsh, Ulster Scots (about one-quarter the colony's population), and other European groups.

On the eve of the American Revolution, close to 6,000 enslaved African Americans and a small population of free blacks also lived in the Commonwealth. Native Americans, however, were driven westward as a result of Europeans' growing numbers and two bitter and deadly wars: The French and Indian War, and the American Revolutionary War. By 1800 only a small Seneca reservation remained in the state.

Ethnic diversity corresponded to a new religious pluralism. Anglicans, Quakers and other dissenters from the Church of England, Evangelical Lutherans, Presbyterians, Moravians, German Reformed, Anabaptists like the Amish and Mennonites, Jews, and Catholics were among the many religious groups that populated Philadelphia and the outlying townships that stretched west across the Allegheny Mountains. By 1800, Pennsylvania had become of a land of cultural contrasts, with a spirited sense of local and community values that has continued to influence Commonwealth politics to the present day. Pennsylvania's diversity also contributed to periodic, and at times deadly conflicts.

Between 1790 and 1860, a second great wave of European immigration coincided with the early industrial revolution, and a growing number of free blacks and runaway slaves escaped to Pennsylvania in their pursuit of freedom. Although substantial numbers of Irish came to Pennsylvania beginning in the late 1700s, a huge new wave of Irish flooded into Philadelphia and other northeastern port cities in the wake of the Potato Famine of the 1840s. Impoverished and Catholic, these Irish newcomers struggled to establish an economic foothold and stable social institutions amidst a rising tide of violent urban rioting and the political backlash of Protestant Nativists. In these same years, African Americans became targets for pent up social prejudices that boiled over on the eve of the Civil War.

During the Civil War, foreign immigration to Pennsylvania declined sharply. Even so, many African Americans, Germans, Irish and other groups sought to secure a greater degree of freedom and social acceptance by supporting the Union cause. Pennsylvanians played key roles as part of the Irish, or "Paddy," and German brigades, and the United States Colored Troops. Following the war, the industrial "Pennsylvania Empire" expanded at an unprecedented pace and an almost insatiable demand for labor in transportation, steel, mining, and other industries drew millions of newcomers to industrial towns and cities across the Commonwealth.

By 1890, southern and eastern European immigrants had replaced the earlier immigrants from western and northern Europe-Old verses New Immigrants, some called them-in the search for a stable and secure future in Pennsylvania. With families and sometimes entire villages following each other, the new immigrants included Italians, Poles, Russians, Hungarians, Czechs and Slovaks, Jews, Greeks, and a multitude of other groups different in language, culture, and identity.

On the eve of the First World War, close to 19 percent of the Commonwealth's population at more than 8 million was foreign-born, and a new and more diverse society was taking shape in Pennsylvania and across urban America. In Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Scranton, Steelton, Coatesville, and other towns across the Commonwealth, ethnically distinct immigrant settlements had formed in close proximity to "native" white neighborhoods. The resulting social interactions were often shaped by a clannishness based on mutual suspicion that disguised the common economic interests each group shared.

What made this mix potentially more volatile was the steady migration of southern blacks drawn by the hope of better jobs and social freedom beyond the Jim Crow South. Moving into Pennsylvania in large numbers between the 1890s and the 1950s-Pennsylvania's African American population would soar from 156,000 in 1900 to more than 1,000,000 in 1970-southern blacks, like earlier generations of migrants, shared the hope that Pennsylvania could offer to a better future for themselves and their descendants.

Anti-immigrant sentiments during the First World War resulted in new federal legislation that cut the great flow of immigration to the United States from a flood to a trickle from the early 1920s to the mid-1960s. In the half-century following the end of the Second World War, many of Pennsylvania's once formidable railroad, steel, mining, textile, and other industries collapsed, and "deindustrialization" exacted a tremendous social and human cost in communities across the Commonwealth. Changes in federal immigration policy after passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 unleashed yet another wave of immigration that has brought hundreds of thousands of newcomers from the Americas, Africa, and Asia into the Commonwealth, and millions to America. Pennsylvania, however, was no longer one of the favored destinations.

In 2008, just 5.3 percent of Pennsylvanians were foreign born: 665,000 of the state's 12,400,000 residents. (That year, by comparison, twelve states had a larger foreign-born population and twenty-nine states had a higher percentage of immigrants than the Commonwealth.) Thirty-seven percent had come from Asia, 27.1 percent from Europe, 28.5 percent from Latin America, 7.2 percent from Africa, 2.4 percent from North America (not including Mexico), and 0.5 percent from Oceania. (Compare this to 1930, when more than 72 percent of Pennsylvania's foreign-born residents had come from southern and eastern Europe.) This latest wave of immigrants tended to be older and better educated than earlier generations of newcomers; indeed, they were 10 percent more likely to have a college degree than native-born Americans over the age of twenty-five.

Although Pennsylvania's historical markers do an excellent documenting the experiences of successive generations of immigrants, these same markers have often neglected the achievements of millions of women who came to Pennsylvania. Single and married women, mothers and wives, domestic workers and those who entered Pennsylvania's vast industrial economy-their stories too are part the broad cloth of Pennsylvania history.

Despite shifting economic and social forces, Pennsylvania's newest immigrants have struggled to preserve their cultural heritage even as they embrace the economic and social possibilities that William Penn imagined centuries ago. Controversial incidents like Hazleton's passage of a local Illegal Immigration Relief Act in 2006, which attracted national attention, serve as a reminder of the persistence of anti-immigrant sentiments in Pennsylvania and across America. The ongoing historical drama of forging a complex multicultural society continues to be at the heart of the Pennsylvania experience in the new millennium.