Chapter 3: The Struggle for Political Rights and Representation (Reformers and Critics)

In the Gilded Age, Pennsylvania businessmen and Republican politicians forged an alliance that insured that the state government, courts, and law enforcement consistently favored the rights of business over workers, public health, and the environment. Pennsylvania was the nation's leading industrial state, so it was only natural that Pennsylvanians also became leaders in the criticism of laissez-faire capitalism and the government institutions that supported it.

Within the political mainstream, Democrats attempted, usually without success, to offer an alternative to voters. In 1868, the Democratic Party considered Lehigh Railroad president and philanthropist

Prominent members of the Republican Party also broke with the party leaders and attempted to reform the party from within, or by creating a third party. In the early 1870s, reformers were strong enough to revise Pennsylvania's state constitution. To make the governor more independent, the Constitution of 1873 extended the term to four years and prevented him from being re-elected in the hope to free him from courting the favors needed to run for a second term. In truth, however, the change strengthened the machine, for a single term limited the power of a popular governor to build a political base or replace political functionaries. The new Constitution also doubled the size of the legislature to increase representation, but instead only increased the graft and boodle to be distributed.

One way the bosses protected and disguised their power was by choosing popular figures with no apparent machine connections for governor, including former Civil War generals

Unrepresented by the two major political parties, many voters turned to dynamic third-party movements, including the Greenback Party in the 1870s, the Grange Party in the 1880s, the Populist Party in the 1890s, and the Socialist Party in the early 1900s. In Pennsylvania, however, farmers and industrial workers by and large remained under the control of the Republicans.

Struggling through decades of often open warfare with the coal companies, voters in the coal-mining regions of northeastern Pennsylvania elected Democrats and in significant numbers joined more radical political organizations, including the Socialist party and International Workers of the World, as did longshoremen and garment workers in Philadelphia. Between 1879 and 1885, Knights of Labor president

The war for political control of the state was also a war for the hearts and minds of Pennsylvanians. Businessmen, philosophers, journalists, and labor organizers all offered their explanations of the extraordinary changes and events taking place in the state, and how citizens should respond to them. The dominant philosophy that justified the capitalist order of the day was Social Darwinism, and one of its most popular spokesmen was

Applying Charles Darwin's theory of evolution to human society, Carnegie argued that the fittest - such as himself - came out on top, and deservedly so, whereas workingmen and unsuccessful businessmen also received the just rewards of their limited abilities. The more the capitalist-philanthropist accumulated, Carnegie argued in The Gospel of Wealth (1889), the more he could act "as trustee and agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do

In rebuttal, labor organizers like Powderly and Maurer offered alternative philosophies and visions of the American economy and politics. Of these reformers, by far the most popular was Philadelphia-born

In the 1880s, Pennsylvania's women joined in the national campaign for voting rights, but after the state legislature in 1885 voted down a call for amendment of the state constitution, their struggle lost momentum until the early 1900s. Careers in journalism, however, gave political voice to women writers, including

In 1904, Californian Lincoln Steffens, one of the nation's most celebrated "muckrakers" - a term coined by Theodore Roosevelt at the turn of the century - wrote exposés of the powerful Republican political machines in

Du Bois also documented the continued

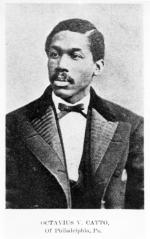

In 1871, a thug hired by Democrats in Philadelphia who opposed black suffrage murdered African-American civic leader

In 1881, the Pennsylvania legislature passed legislation

From the 1870s through the 1890s, Pennsylvania reformers could point out what was wrong in the Commonwealth, but they couldn't do much about it. The struggle for reform, however, would gain nationwide momentum in the 1890s, and in the early 1900s coalesce in a wave of Progressive era reforms and political realignments.