Chapter 3: Pennsylvania Football

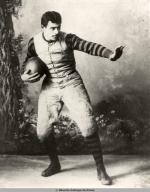

In the 1870s, upperclassmen at the University of Pennsylvania began to initiate freshmen through a new intramural sport called football, a rough-and-tumble American variation of the English game of rugby, which provided ample opportunities for organized assaults, and the release of pent up energies and aggressions. The game had no standardized rules, strategies, or scoring system until the 1880s–and even then nothing was carved in stone–but its evolution seemed very much in sync with ongoing changes in American society.

The collegians added structure, discipline, and regimentation to the controlled mayhem they had inherited, as the game came to reflect America's emerging industrial economy and society. Like baseball, the game fostered competition and teamwork, two essential qualities advanced by industrial capitalism. But in football, players divided into skilled and unskilled positions, the game was run by clock, and each play, designed to drive deeper into the opponent's territory, was like a new work shift. Fearful that the modern world was softening American manhood, middle-class and elite Americans embraced football's aggressive nature and the courage and muscular vitality it required. Victory in the increasingly popular intercollegiate game came through brutal physical combat and coordinated assault. Twenty players on each side had three chances to move the ball five yards for a first down, and they did so through charges of brute force, gang tackling, and kicks of the ball into the opponents' territory.

As the first collegiate players moved beyond the ivied halls of the academy, the game graduated with them to the athletic clubs and associations they joined. By the 1880s, the sporting associations and amateur athletic clubs that had formed earlier in the century around other sports like baseball, cricket, and rowing began sponsoring football teams, as well. And the game spread. In Pennsylvania it had particular appeal in the coal towns of western and northeastern Pennsylvania, and the steel towns around Pittsburgh and in Bethlehem. Football's appeal among blue-collar workers and immigrants was magnetic; the game called for the same kind of grit they had to muster just to get by every day.

Bethlehem. Football's appeal among blue-collar workers and immigrants was magnetic; the game called for the same kind of grit they had to muster just to get by every day.

On the field, competition among clubs was as fierce as it was among the colleges. Pride was at stake. So, too, was money. Even then, betting on football was as passionate as it was pervasive, so off the field competition for the best players could be ferocious. It was no secret that bigger clubs regularly tip-toed around amateur regulations by bringing in college boys and other ringers with the same kinds of under-the-table incentives–from cash to job offers–that pre-professional baseball had employed.

among the colleges. Pride was at stake. So, too, was money. Even then, betting on football was as passionate as it was pervasive, so off the field competition for the best players could be ferocious. It was no secret that bigger clubs regularly tip-toed around amateur regulations by bringing in college boys and other ringers with the same kinds of under-the-table incentives–from cash to job offers–that pre-professional baseball had employed.

On November 12, 1892, that changed. The Allegheny Athletic Association, anxious to beat their cross-town rival, the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, lured former Yale All-American William "Pudge" Heffelfinger, the most celebrated footballer of his day, to join their squad that afternoon with a $500 carrot. That payment, kept quiet for years, turned the afternoon's wild proceedings into what has become accepted as the first professional football game. By the following year, teams were putting players under early contracts.

first professional football game. By the following year, teams were putting players under early contracts.

It would take decades for the professional game even to begin approaching the collegiate variety in popularity. In the 1890s, as the United States battled for overseas colonies and joined the ranks of the world powers, the popularity of college football soared. But so, too, did injuries and deaths among the nation's finest young men. In December 1905, thirteen schools met in New York to determine the fate of college football. Moved by the eloquence of Haverford College athletic director James Babbitt for reform rather than abolition, eight of them, including Haverford and Swarthmore, voted to continue the game. Later that month a conference of more than sixty colleges formed the Inter-College Athletic Association- in 1910 renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association- to change the rules and outlaw professionalism.

To reduce the brutality of the sport, the Association changed the rules to open the game up, and legalized the forward pass, an innovation championed by Coach John Heisman, who had played varsity football for Penn in 1890-91. The changes worked, turning the game from one of brute strength into one that matched strength with speed and dexterity. As football's popularity soared, a new batch of heroes emerged, including two–coach Pop Warner and his greatest star, Jim Thorpe – from an unlikely venue: the Carlisle Indian School.

the Carlisle Indian School.

Thorpe went on to play professionally from 1913 to 1925, at first with a Pennsylvania squad in Pine Valley, then with bigger teams in Canton, Toledo, and New York in the first years of the new National Football League (NFL). The new league, founded in 1920–the year before Pittsburgh radio station KDKA aired the first football game, a collegiate contest between Pitt and West Virginia from Forbes Field–tried desperately to get a toe-hold in larger cities. Though it managed to place teams in Chicago and New York, the majority of the early NFL franchises were off-shoots of industrial and factory-league squads in smaller towns like Green Bay, Kenosha, and Pottsville, Pennsylvania, an anthracite coal town where a blue-collar, often immigrant fan base embraced the game.

KDKA aired the first football game, a collegiate contest between Pitt and West Virginia from Forbes Field–tried desperately to get a toe-hold in larger cities. Though it managed to place teams in Chicago and New York, the majority of the early NFL franchises were off-shoots of industrial and factory-league squads in smaller towns like Green Bay, Kenosha, and Pottsville, Pennsylvania, an anthracite coal town where a blue-collar, often immigrant fan base embraced the game.

In the league's earliest years, most middle-class American sport fans dismissed professional football as a barnstorming sideshow, a sorry stepchild to its nobler collegiate relation; they were far more interested, for example, in a small college from southwest Pennsylvania, Washington and Jefferson, holding mighty California to a scoreless tie than in anything the pros were doing. Indeed, the 1920s and 1930s marked the Golden Age of college football, and it was a particularly glittering time for western Pennsylvania's college elevens. Carnegie Tech twice beat powerhouse Notre Dame, and Duquesne won the Orange Bowl in 1934 and 1937. Meanwhile, the University of Pittsburgh, which won national championships in 1916 and 1918 under Pop Warner, won back-to-back titles for Coach Jock Sutherland in 1936 and 1937.

The second-class aura around the professional game began changing when the great Illinois running back Red Grange left school to join the Chicago Bears at the end of the 1925 season. His presence gave the game an immediate boost in class, credibility, and respectability. The league's champion that year, the

Red Grange left school to join the Chicago Bears at the end of the 1925 season. His presence gave the game an immediate boost in class, credibility, and respectability. The league's champion that year, the  Pottsville Maroons, soon moved to the much larger Boston market. By the early 1930s, professional teams were playing in both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Pottsville Maroons, soon moved to the much larger Boston market. By the early 1930s, professional teams were playing in both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Football also flourished in other arenas. Factories, mills, and mines sponsored worker teams to help build pride and morale. In the early 1900s, communities came together to sponsor both amateur sandlot and professional teams; the latter would continue on even after the formation of the NFL through a string of minor-league circuits. There were also all-black teams, none better than the Garfield Eagles, so dominant in the sandlots of Pittsburgh against black and white competition alike during the 1930s that they were often called the Homestead Grays of their sport.

In the north, collegiate football was integrated. In the late teens, African-American player Paul Robeson was named an All-American at Rutgers and Fritz Pollard an All-American at Brown. Both starred in the nascent NFL, with Pollard becoming the league's first black coach in 1921; in 1923 and 1924 he also led the Gilberton Cadamounts to successful campaigns in the semi-professional Pennsylvania "Coal League." At the onset of the Depression, however, blacks were banned from the NFL, and would remain so until just after World War II, when the owners, including the Steelers" Art Rooney, spurred by Commissioner

Art Rooney, spurred by Commissioner  Bert Bell, once again agreed to integrate their teams.

Bert Bell, once again agreed to integrate their teams.

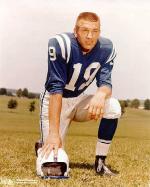

In the 1950s, a black quarterback from western Pennsylvania named Willie Thrower rewrote the high-school record books; he then went on to become the first black quarterback in the modern NFL. At the same time another hardscrabble signal caller named

Willie Thrower rewrote the high-school record books; he then went on to become the first black quarterback in the modern NFL. At the same time another hardscrabble signal caller named  Johnny Unitas emerged from the Pittsburgh sandlots to redefine the position, piloting the Baltimore Colts to NFL titles in 1958 and 1959. Unitas was just one in a parade of Hall of Fame quarterbacks, including Joe Namath, Dan Marino, and Joe Montana, to march from western Pennsylvania into the national spotlight.

Johnny Unitas emerged from the Pittsburgh sandlots to redefine the position, piloting the Baltimore Colts to NFL titles in 1958 and 1959. Unitas was just one in a parade of Hall of Fame quarterbacks, including Joe Namath, Dan Marino, and Joe Montana, to march from western Pennsylvania into the national spotlight.

In the 1970s, football began to challenge baseball as the nation's favorite spectator sport, its popularity driven and its pockets enriched by television. Pennsylvania would remain a football powerhouse. After winning their third league championship in 1960, the Philadelphia Eagles entered a period of decline, but between 1975 and 1980, the Steelers twice won Super Bowls back to back, then added a fifth in 2006, and sixth in 2009.

The University of Pittsburgh joined the fun in 1976 by once again being named national collegiate champion, a crown that Penn State would wear in 1982 and 1986. The 1970s also saw the birth of the multi-purpose stadiums, with Veterans Stadium replacing the far more intimate

Veterans Stadium replacing the far more intimate  Shibe Park in Philadelphia and Three Rivers Stadium supplanting Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Both behemoths gave way in the twenty-first century to new, state-of-the-art baseball and football stadiums in each city.

Shibe Park in Philadelphia and Three Rivers Stadium supplanting Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Both behemoths gave way in the twenty-first century to new, state-of-the-art baseball and football stadiums in each city.

By then, of course, football had long since cloaked itself in the mantle of "America's Game." Television has made the sport rich, and free agency has created a new class of sporting plutocrats in helmets and shoulder pads. And if football has also suffered such modern ills as cocaine and steroids, it continues to inspire and entrance. On any given Saturday, more than 100,000 fans fill Beaver Stadium when Penn State plays at home, and fans in both Philadelphia and Pittsburgh live and die with their team's fortunes.

The collegians added structure, discipline, and regimentation to the controlled mayhem they had inherited, as the game came to reflect America's emerging industrial economy and society. Like baseball, the game fostered competition and teamwork, two essential qualities advanced by industrial capitalism. But in football, players divided into skilled and unskilled positions, the game was run by clock, and each play, designed to drive deeper into the opponent's territory, was like a new work shift. Fearful that the modern world was softening American manhood, middle-class and elite Americans embraced football's aggressive nature and the courage and muscular vitality it required. Victory in the increasingly popular intercollegiate game came through brutal physical combat and coordinated assault. Twenty players on each side had three chances to move the ball five yards for a first down, and they did so through charges of brute force, gang tackling, and kicks of the ball into the opponents' territory.

As the first collegiate players moved beyond the ivied halls of the academy, the game graduated with them to the athletic clubs and associations they joined. By the 1880s, the sporting associations and amateur athletic clubs that had formed earlier in the century around other sports like baseball, cricket, and rowing began sponsoring football teams, as well. And the game spread. In Pennsylvania it had particular appeal in the coal towns of western and northeastern Pennsylvania, and the steel towns around Pittsburgh and in

On the field, competition among clubs was as fierce as it was

On November 12, 1892, that changed. The Allegheny Athletic Association, anxious to beat their cross-town rival, the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, lured former Yale All-American William "Pudge" Heffelfinger, the most celebrated footballer of his day, to join their squad that afternoon with a $500 carrot. That payment, kept quiet for years, turned the afternoon's wild proceedings into what has become accepted as the

It would take decades for the professional game even to begin approaching the collegiate variety in popularity. In the 1890s, as the United States battled for overseas colonies and joined the ranks of the world powers, the popularity of college football soared. But so, too, did injuries and deaths among the nation's finest young men. In December 1905, thirteen schools met in New York to determine the fate of college football. Moved by the eloquence of Haverford College athletic director James Babbitt for reform rather than abolition, eight of them, including Haverford and Swarthmore, voted to continue the game. Later that month a conference of more than sixty colleges formed the Inter-College Athletic Association- in 1910 renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association- to change the rules and outlaw professionalism.

To reduce the brutality of the sport, the Association changed the rules to open the game up, and legalized the forward pass, an innovation championed by Coach John Heisman, who had played varsity football for Penn in 1890-91. The changes worked, turning the game from one of brute strength into one that matched strength with speed and dexterity. As football's popularity soared, a new batch of heroes emerged, including two–coach Pop Warner and his greatest star, Jim Thorpe – from an unlikely venue:

Thorpe went on to play professionally from 1913 to 1925, at first with a Pennsylvania squad in Pine Valley, then with bigger teams in Canton, Toledo, and New York in the first years of the new National Football League (NFL). The new league, founded in 1920–the year before Pittsburgh radio station

In the league's earliest years, most middle-class American sport fans dismissed professional football as a barnstorming sideshow, a sorry stepchild to its nobler collegiate relation; they were far more interested, for example, in a small college from southwest Pennsylvania, Washington and Jefferson, holding mighty California to a scoreless tie than in anything the pros were doing. Indeed, the 1920s and 1930s marked the Golden Age of college football, and it was a particularly glittering time for western Pennsylvania's college elevens. Carnegie Tech twice beat powerhouse Notre Dame, and Duquesne won the Orange Bowl in 1934 and 1937. Meanwhile, the University of Pittsburgh, which won national championships in 1916 and 1918 under Pop Warner, won back-to-back titles for Coach Jock Sutherland in 1936 and 1937.

The second-class aura around the professional game began changing when the great Illinois running back

Football also flourished in other arenas. Factories, mills, and mines sponsored worker teams to help build pride and morale. In the early 1900s, communities came together to sponsor both amateur sandlot and professional teams; the latter would continue on even after the formation of the NFL through a string of minor-league circuits. There were also all-black teams, none better than the Garfield Eagles, so dominant in the sandlots of Pittsburgh against black and white competition alike during the 1930s that they were often called the Homestead Grays of their sport.

In the north, collegiate football was integrated. In the late teens, African-American player Paul Robeson was named an All-American at Rutgers and Fritz Pollard an All-American at Brown. Both starred in the nascent NFL, with Pollard becoming the league's first black coach in 1921; in 1923 and 1924 he also led the Gilberton Cadamounts to successful campaigns in the semi-professional Pennsylvania "Coal League." At the onset of the Depression, however, blacks were banned from the NFL, and would remain so until just after World War II, when the owners, including the Steelers"

In the 1950s, a black quarterback from western Pennsylvania named

In the 1970s, football began to challenge baseball as the nation's favorite spectator sport, its popularity driven and its pockets enriched by television. Pennsylvania would remain a football powerhouse. After winning their third league championship in 1960, the Philadelphia Eagles entered a period of decline, but between 1975 and 1980, the Steelers twice won Super Bowls back to back, then added a fifth in 2006, and sixth in 2009.

The University of Pittsburgh joined the fun in 1976 by once again being named national collegiate champion, a crown that Penn State would wear in 1982 and 1986. The 1970s also saw the birth of the multi-purpose stadiums, with

By then, of course, football had long since cloaked itself in the mantle of "America's Game." Television has made the sport rich, and free agency has created a new class of sporting plutocrats in helmets and shoulder pads. And if football has also suffered such modern ills as cocaine and steroids, it continues to inspire and entrance. On any given Saturday, more than 100,000 fans fill Beaver Stadium when Penn State plays at home, and fans in both Philadelphia and Pittsburgh live and die with their team's fortunes.

![Top Row: Mac Curtin, Bill Stuart, Charles Thomas, E.V. Rawn, Butch Cromish, A.F. Dole. 2nd Row: George Spencer[Manager], J.M. McKibbin, J.G. Dunmore, G. W. Hoskins [Trainer], B.F. Fisher [Captain], J.A. Dunsmore, Charlie Atherton, Fred Robinson. Bottom Row: I.K. Dixon, C.E.Scott, C.M. Thompson, H.M. Suter, J.L. Harris, W. McCashey Top Row: Mac Curtin, Bill Stuart, Charles Thomas, E.V. Rawn, Butch Cromish, A.F. Dole. 2nd Row: George Spencer[Manager], J.M. McKibbin, J.G. Dunmore, G. W. Hoskins [Trainer], B.F. Fisher [Captain], J.A. Dunsmore, Charlie Atherton, Fred Robinson. Bottom Row: I.K. Dixon, C.E.Scott, C.M. Thompson, H.M. Suter, J.L. Harris, W. McCashey](http://cache.matrix.msu.edu/expa/small/1-2-1408-25-ExplorePAHistory-a0l0x2-a_349.jpg)