Overview: The Pennsylvania Iron Industry: Furnace and Forge of America

"Pennsylvania, in regard to its iron-works, is the most advanced of all the American colonies."

Israel Acrelius, 1759

By 1759, when Acrelius published this observation, colony ironmasters had already erected almost fifty furnaces and forges. For more than a century, Pennsylvania was the ironmaking center of America. The iron industry played a critical role in the development of the English colonies and the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Iron was an essential material in the agricultural colonies and industrializing nation. Americans relied on a vast array of iron products, from tools for blacksmiths and wheel rims for carriages, to steam locomotives and iron rails. Until the large-scale production of steel in the late nineteenth century, iron proved superior in strength and durability for myriad uses.

Pennsylvania led the colonies and nation in iron production. After independence, the nation's output of iron grew enormously, from 54,000 tons in 1810 to 286,000 tons in 1840. During this era, Pennsylvania consistently produced half of the national total. In 1870 Pennsylvania manufactured $123 million worth of iron, more than twice that of New York, the second-ranking state.

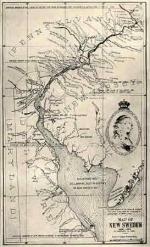

Pennsylvania was the leading iron manufacturer in large measure because of its natural resources and growing markets for iron products. The Commonwealth was blessed with iron ore deposits, vast forests that provided charcoal, abundant coal beds that also supplied fuel, the limestone used as flux, and streams for water power. Early residents of the colony noted these resources, particularly iron ore deposits. William Penn wrote in 1681 of the potential for iron production and encouraged others to establish ironworks in his colony.

The iron industry began in Pennsylvania in 1716 in Berks County, when ironmasters erected a bloomery forge that produced crude iron. By the tiem of the American Revolution, ironmasters had erected more than seventy iron furnaces and forges, all fueled by charcoal, in the Schuylkill, Delaware, and Susquehanna River valleys. Iron furnaces smelted iron ore into iron, and forges re-heated and hammered this iron into various wrought-iron products. By the early 1800s, ironmasters had followed settlers and demand for iron westward and firmly established the industry in the Juniata River region and west of the Alleghenies.

Before 1840 most iron manufacturing took place on large iron plantations in furnaces that relied on charcoal for fuel, and that using technology adopted from Britain in the early eighteenth century. Furnaces and forges typically stood at the center of rural iron plantations – large complexes of production facilities, workers' housing, ironmaster's mansion, store, forests, and often iron ore deposits. Ironmasters generally were paternalistic managers of workers and relied on employees to labor obediently, steadily, and well. Workers depended on ironmasters for their employment, but they also sometimes defied them, by leaving work or performing it negligently.

Between 1840 and 1880 the iron industry experienced profound technological changes, including a shift in fuel from charcoal to anthracite coal and then to bituminous coal and coke. During the 1840s and 1850s furnaces fueled by anthracite superseded charcoal furnaces, and rolling mills replaced forges. By the 1870s furnaces fired with bituminous coal and coke supplanted anthracite furnaces. In 1872, fully 86 percent of Pennsylvania furnaces used anthracite and/or bituminous coal and coke.

These major changes in fuel sources and technology enabled ironmasters to improve efficiency, decrease costs, and increase output greatly in order to meet demand from growing railroads that needed iron rails. They also fostered larger production facilities and labor forces, and greater integration of iron furnaces with rolling mills.

As part of their drive to increase efficiency and reduce costs, ironmasters increasingly viewed workers as a cost to be cut. Employees, in turn, increasingly saw their interests as counter to their employers', and went on strike and organized unions. Skilled workers, who had more power and autonomy, led organizing efforts. In 1858 skilled puddlers in Pittsburgh founded the Sons of Vulcan, which became a national union in 1862. This organization joined with other unions in 1876 to form the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, which helped win better wages for workers.

Iron production continued to evolve after 1880 with the rise of the steel industry. Steel mills manufactured iron in iron furnaces and then converted the iron into steel. The Pennsylvania Steel Company began the first commercially successful production of steel in the nation in 1867 at Steelton. Railroads demanded stronger, more durable steel rails, and technological innovations, including the Bessemer converter, facilitated the manufacture of steel in large quantities at prices cheaper than iron. Steel firms first took over rail production, then structural shapes, and later almost all other products that had been made of iron.

The output of America's steel mills first surpassed iron production in 1892. Steel mills integrated coke-fueled iron furnaces to supply pig iron to steel furnaces. To feed their growing steel furnaces and meet rising demand, steel companies increased the size, output, and efficiency of their associated iron furnaces. Steel masters also integrated all phases of the industry, from acquiring raw materials to marketing finished products. In addition, they also merged companies into gargantuan corporations, culminating in 1901 with the formation of the United States Steel Corporation, which controlled sixty percent of all pig iron production, and 66 percent of all crude steel made in the nation.

Despite the dominance of the steel industry, some independent iron manufacturers thrived during the late nineteenth century. Independent ironworks survived by establishing market niches for themselves. Some specialized in wrought-iron products that were higher quality than steel, which larger steel companies avoided because there was too little demand, or that required skilled workers to produce. In addition, some independents supplied pig iron to steel mills or manufactured small quantities of steel themselves. When, for example, the Lochiel Iron Company, organized in Harrisburg in 1864, failed in competition with steel rails manufactured at the nearby Pennsylvania Steel Company plant, its owners shifted production to boiler, tank, and ship plate, and to the sale of pig iron to the Pennsylvania Steel Company.

In Pittsburgh eleven of forty independent iron and steel mills founded before 1896 survived until 1938, while ten new independents began production. These firms' productive capacity doubled between 1901 and 1938. Like much of the rest of the industry, however, the number of independent Pittsburgh iron and steel firms and their production fell thereafter. Only a handful of independent iron companies operated by the end of World War II. The Shenango Furnace Company, which had begun production in 1901 near Pittsburgh, ran two of the last independent iron furnaces, finally shutting down in 1990.

Today, little is left of the once powerful Pennsylvania iron industry, but reminders of that industry still remain. Cornwall Furnace in Lebanon County has survived as an exceptionally well-preserved charcoal furnace. Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site has restored part of a charcoal iron plantation in Berks County. Four furnaces in Scranton are among the few anthracite furnaces that have survived. Other, mostly decaying charcoal furnaces are scattered across Pennsylvania.