Chapter 2: Refugees, Traders, and Missionaries: Indians, Colonists, and the Remaking of Pennsylvania, 1600-1753

Benjamin West's painting Penn's Treaty with the Indians (1771) is the most widely recognized representation of Pennsylvania's founding. In it, an open-armed and somewhat rotund William Penn meets with local Indians upon his arrival in America in 1682. The Indians–men, women, and children–gather around Penn and his companions, some of them skeptical and others fascinated, but all with their attention riveted on the bolt of trade cloth at the center of the painting. Other visual clues forecast what will come next. To the left are the boats that will carry settlers to Penn's new colony, to occupy the half-finished buildings in the background. To the right, an Indian male walks back toward the woods, carrying on his shoulder a bolt of cloth for which he has bargained.

With remarkable detail, West delivered in his most famous painting the story of Pennsylvania's mythic founding encounter: Native Americans peacefully met William Penn on the coast, traded their land for manufactured goods, and then receded west so that newcomers might occupy their homelands.

The story of the Indians' encounter with Europeans, however, was much more complicated than this. West completed this painting almost a century after the scene it depicts, and historians are not even sure such a treaty took place. For the native peoples of Pennsylvania, the arrival of Europeans was fraught with perils as well as pleasures. Cloth, metal tools, and other trade goods attracted Indians, but the people who brought such objects also carried diseases, weapons, and alcohol that destroyed Indian populations and cultures.

Intercultural diplomacy offered a means of negotiating differences between natives and newcomers, but it was also an avenue for dispossession by land purchases. Indians who agreed at such treaties to allow colonists a certain use of their land often found out later that Europeans interpreted such documents to mean that Indians had surrendered to them the land and all its uses forever. European missionaries studied Indian languages and sometimes served as valuable advocates on the Indians' behalf, but their religious principles also led them to denigrate the Indians' own cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

The disruptions caused by the European colonization of America profoundly altered life for Indians, uprooting many of them and reshaping the cultural and political map of the colony in the process. On the eve of the French and Indian War in 1753, the Indians' relationship with the colonial newcomers looked much different than it had a century and half earlier.

Trade Networks

Following Benjamin West's lead, it is tempting to see Penn's Treaty as the start of the European-Indian encounter in Pennsylvania. That memorable occasion, however, would have taken place after decades of contact, trade, and colonization. Indeed, the first Englishman to write a description of Indians who lived in what would become Pennsylvania was Captain John Smith, whom we typically associate with Pocahontas and the founding of Jamestown in Virginia.

Penn's Treaty as the start of the European-Indian encounter in Pennsylvania. That memorable occasion, however, would have taken place after decades of contact, trade, and colonization. Indeed, the first Englishman to write a description of Indians who lived in what would become Pennsylvania was Captain John Smith, whom we typically associate with Pocahontas and the founding of Jamestown in Virginia.

Exploring the northern reaches of Chesapeake Bay in 1608 Smith encountered the Susquehannocks,who lived in a river valley to the north. Awestruck by their size and strength, he described them as "giants" whose voices echoed when they spoke as if coming from a vault or cave. Even more interesting, the Susquehannocks already had in their possession European beads and metal that they must have acquired by trading with Indians to the north in Canada and to the east along the Delaware River. Although strangers to Smith, they were already knitted into patterns of trade with Europeans established along coastline and inland water routes of North America.

Susquehannocks,who lived in a river valley to the north. Awestruck by their size and strength, he described them as "giants" whose voices echoed when they spoke as if coming from a vault or cave. Even more interesting, the Susquehannocks already had in their possession European beads and metal that they must have acquired by trading with Indians to the north in Canada and to the east along the Delaware River. Although strangers to Smith, they were already knitted into patterns of trade with Europeans established along coastline and inland water routes of North America.

Those networks of trade became more developed in the Pennsylvania region when Dutch and Swedish colonizers appeared on the Delaware River in the 1620s and 1630s. Both of these groups were interested in extending the European fur trade from coastal regions into the Delaware, Schuylkill, and Susquehanna valleys. Possessing tools made only of stone, bone, and wood, Indians acquired copper kettles, cloth, knives, axes, hoes, guns, and a variety of other goods from the newcomers. These traders inadvertently transmitted to the Indians smallpox, measles, and other diseases to which they had no previous exposure.

The result was a devastating decline in native populations, as high as 90 precent in some regions. European trade goods, on the other hand, at first had little disruptive impact on the Indians' lives. Most were either novelty items valued for their rarity or useful substitutes for native-manufactured goods: kettles replaced pottery as cooking vessels, woven cloth replaced animal skins for clothing, and metal knives and hatchets replaced similar items made of stone.

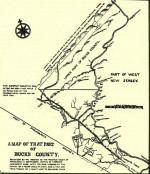

The fur trade set in motion all sorts of processes that reshaped the Indians" Pennsylvania. Over-hunting of animals gradually pushed the trade west, as Indian hunters and European traders sought new sources of furs. The Indian paths that connected the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Allegheny-Ohio watersheds became the interior routes of the trade, and new Indian communities, such as Frankstown, sprang up in western Pennsylvania.

Frankstown, sprang up in western Pennsylvania.

The fur trade also attracted Indians to the Pennsylvania interior who had been displaced elsewhere by disease or warfare. Algonquian nations from the Chesapeake Bay moved into the Pennsylvania interior by way of the Susquehanna Valley, creating communities such as Conoy Town and Shamokin. Farther west, Shawnee, Delaware, and Iroquois peoples moved into the Allegheny and Upper Ohio valleys and established communities such as

Conoy Town and Shamokin. Farther west, Shawnee, Delaware, and Iroquois peoples moved into the Allegheny and Upper Ohio valleys and established communities such as  Queen Aliquippa's Town and

Queen Aliquippa's Town and  Logstown.

Logstown.

By the middle of the 1700s, Indians living within the borders of Pennsylvania included a host of peoples–Tuscaroras, Nanticokes, Mahicans, and many others–who had been dispossessed from their homelands in North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York by war and colonization. For such displaced peoples, Pennsylvania seemed a bountiful refuge, still rich with fur-bearing animals and home to a colonial government with a reputation for fair dealing with Indian neighbors.

Diplomacy and Religion

The mingling of native and colonial peoples in Pennsylvania created a need for go-betweens who could conduct diplomacy and business among these various communities. Such negotiators usually emerged from the fur trade, which became an avenue for intermarriage, adoption, and language acquisition across cultural boundaries. The Montour family, a product of two generations of intermarriage between Europeans and Indians, played such a role in the Susquehanna and Allegheny valleys.

Montour family, a product of two generations of intermarriage between Europeans and Indians, played such a role in the Susquehanna and Allegheny valleys.  Conrad Weiser, a German immigrant to the Tulpehocken Valley who had lived among the Mohawks as a boy, became an indispensable interpreter for the Pennsylvania government. One of Weiser's Indian counterparts was

Conrad Weiser, a German immigrant to the Tulpehocken Valley who had lived among the Mohawks as a boy, became an indispensable interpreter for the Pennsylvania government. One of Weiser's Indian counterparts was  Shickellamy, an Oneida who lived at Shamokin on the forks of the Susquehanna, and who mediated relations between the Iroquois, Delaware, and several other native and colonial groups.

Shickellamy, an Oneida who lived at Shamokin on the forks of the Susquehanna, and who mediated relations between the Iroquois, Delaware, and several other native and colonial groups.

Religion provided another avenue of cultural exchange and accommodation. Unlike the Puritans, Anglicans, and French Catholic colonizers around them, the Quaker founders of Pennsylvania did not sponsor specific missionary orders or organizations to turn Indians into Christian converts. By the 1740s, however, other European immigrants to Pennsylvania had brought to the colony their own missionary zeal and methods. David Brainerd, a New England Presbyterian, came to Pennsylvania to win converts among the Delaware who lived on the Forks of the Delaware. His interpreter,

David Brainerd, a New England Presbyterian, came to Pennsylvania to win converts among the Delaware who lived on the Forks of the Delaware. His interpreter,  Moses Tunda Tatamy, became his first convert and most important agent among the Indians he sought to convert.

Moses Tunda Tatamy, became his first convert and most important agent among the Indians he sought to convert.

Despite his efforts, Brainerd met with little success because of his failure to immerse himself in the Indian communities to whom he preached. More successful were the Moravians, a German sect that made Bethlehem their headquarters in North America. Moravian missionaries picked up where Brainerd left off at the Forks of the Delaware and in the 1700s extended their missions into the Susquehanna, Allegheny, and Ohio valleys. While they won more converts than Brainerd, most of the Indians these missionaries encountered politely declined the opportunity to convert, expressing a preference for the spiritual values and beliefs of their ancestors.

The work of colonial agents, traders, and missionaries was creative and adaptive. Intercultural commerce, communication, and religion encouraged different peoples to learn each other's languages, customs, and manners, so that new hybrid forms might build bridges between them. Such cultural borrowing and imitation defined the nature of European-Indian diplomacy in colonial Pennsylvania, which was constantly employed to extend trade, win converts, and keep the peace.

Throughout the colonial era, treaty conferences convened in locations like Philadelphia, Easton, Logstown, and Carlisle, where participants engaged in speech-making and gift exchange to advance their interests against one another. This process was seldom as peaceful or friendly as West depicted in Penn's Treaty with the Indians, but it did provide a basis for mutual understanding and communication so long as each party acted in good faith toward the other.

Indian Dispossession

Unfortunately, nothing eroded that good faith more severely than the Europeans' pursuit of Indian lands. The Dutch and the Swedes came in small numbers and primarily for trade, but after Penn's colony was established in 1682, droves of settlers recruited by the Penn family in Britain, Ireland, and Germany began arriving. By the early decades of the eighteenth century, this onslaught of newcomers was displacing Indians from the Delaware and lower Susquehanna valleys.

Indian dispossession was accelerated by the Penn family's desire for land. William Penn's heirs, who remained in England and tended to regard their colony as a real estate investment, relied on the Philadelphia merchant James Logan to conduct Indian affairs on their behalf. Logan profited handsomely from the fur trade and land sales, and never missed a chance to wheedle more territory out of Indian hands. During the 1730s and 1740s, he brought Pennsylvania into the Iroquois confederacy's Covenant Chain alliance with the British colonies.

The Iroquois, their homelands located in modern upstate New York, claimed to own most of Pennsylvania's frontier by right of conquest from the Delaware and Susquehannocks. Logan and other Pennsylvania officials were more than happy to recognize that claim, so long as the Iroquois remained willing to sell land to the Penn family. Locked out of this process were the actual inhabitants of the land in question, primarily Delaware and Shawnee who lived in the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Ohio-Allegheny valleys.

By the mid-1700s, the high-handed and fraudulent tactics employed by Logan and the Penn family in acquiring land had soured Indian relations within the colony. The infamous Walking Purchase forced the Indians living at the Forks of the Delaware to move west against their wishes. Along Pennsylvania's western frontier, squatter communities such as

Walking Purchase forced the Indians living at the Forks of the Delaware to move west against their wishes. Along Pennsylvania's western frontier, squatter communities such as  Burnt Cabins defied the efforts of colonial officials to remove them and aggravated neighboring Indians.

Burnt Cabins defied the efforts of colonial officials to remove them and aggravated neighboring Indians.

The contest for land eroded the goodwill that go-betweens, traders, and missionaries relied on in conducting their affairs. During the 1750s, their efforts collapsed under the strain of war, unleashing unprecedented violence between Indians and colonists on the Pennsylvania frontier.

With remarkable detail, West delivered in his most famous painting the story of Pennsylvania's mythic founding encounter: Native Americans peacefully met William Penn on the coast, traded their land for manufactured goods, and then receded west so that newcomers might occupy their homelands.

The story of the Indians' encounter with Europeans, however, was much more complicated than this. West completed this painting almost a century after the scene it depicts, and historians are not even sure such a treaty took place. For the native peoples of Pennsylvania, the arrival of Europeans was fraught with perils as well as pleasures. Cloth, metal tools, and other trade goods attracted Indians, but the people who brought such objects also carried diseases, weapons, and alcohol that destroyed Indian populations and cultures.

Intercultural diplomacy offered a means of negotiating differences between natives and newcomers, but it was also an avenue for dispossession by land purchases. Indians who agreed at such treaties to allow colonists a certain use of their land often found out later that Europeans interpreted such documents to mean that Indians had surrendered to them the land and all its uses forever. European missionaries studied Indian languages and sometimes served as valuable advocates on the Indians' behalf, but their religious principles also led them to denigrate the Indians' own cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

The disruptions caused by the European colonization of America profoundly altered life for Indians, uprooting many of them and reshaping the cultural and political map of the colony in the process. On the eve of the French and Indian War in 1753, the Indians' relationship with the colonial newcomers looked much different than it had a century and half earlier.

Trade Networks

Following Benjamin West's lead, it is tempting to see

Exploring the northern reaches of Chesapeake Bay in 1608 Smith encountered the

Those networks of trade became more developed in the Pennsylvania region when Dutch and Swedish colonizers appeared on the Delaware River in the 1620s and 1630s. Both of these groups were interested in extending the European fur trade from coastal regions into the Delaware, Schuylkill, and Susquehanna valleys. Possessing tools made only of stone, bone, and wood, Indians acquired copper kettles, cloth, knives, axes, hoes, guns, and a variety of other goods from the newcomers. These traders inadvertently transmitted to the Indians smallpox, measles, and other diseases to which they had no previous exposure.

The result was a devastating decline in native populations, as high as 90 precent in some regions. European trade goods, on the other hand, at first had little disruptive impact on the Indians' lives. Most were either novelty items valued for their rarity or useful substitutes for native-manufactured goods: kettles replaced pottery as cooking vessels, woven cloth replaced animal skins for clothing, and metal knives and hatchets replaced similar items made of stone.

The fur trade set in motion all sorts of processes that reshaped the Indians" Pennsylvania. Over-hunting of animals gradually pushed the trade west, as Indian hunters and European traders sought new sources of furs. The Indian paths that connected the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Allegheny-Ohio watersheds became the interior routes of the trade, and new Indian communities, such as

The fur trade also attracted Indians to the Pennsylvania interior who had been displaced elsewhere by disease or warfare. Algonquian nations from the Chesapeake Bay moved into the Pennsylvania interior by way of the Susquehanna Valley, creating communities such as

By the middle of the 1700s, Indians living within the borders of Pennsylvania included a host of peoples–Tuscaroras, Nanticokes, Mahicans, and many others–who had been dispossessed from their homelands in North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York by war and colonization. For such displaced peoples, Pennsylvania seemed a bountiful refuge, still rich with fur-bearing animals and home to a colonial government with a reputation for fair dealing with Indian neighbors.

Diplomacy and Religion

The mingling of native and colonial peoples in Pennsylvania created a need for go-betweens who could conduct diplomacy and business among these various communities. Such negotiators usually emerged from the fur trade, which became an avenue for intermarriage, adoption, and language acquisition across cultural boundaries. The

Religion provided another avenue of cultural exchange and accommodation. Unlike the Puritans, Anglicans, and French Catholic colonizers around them, the Quaker founders of Pennsylvania did not sponsor specific missionary orders or organizations to turn Indians into Christian converts. By the 1740s, however, other European immigrants to Pennsylvania had brought to the colony their own missionary zeal and methods.

Despite his efforts, Brainerd met with little success because of his failure to immerse himself in the Indian communities to whom he preached. More successful were the Moravians, a German sect that made Bethlehem their headquarters in North America. Moravian missionaries picked up where Brainerd left off at the Forks of the Delaware and in the 1700s extended their missions into the Susquehanna, Allegheny, and Ohio valleys. While they won more converts than Brainerd, most of the Indians these missionaries encountered politely declined the opportunity to convert, expressing a preference for the spiritual values and beliefs of their ancestors.

The work of colonial agents, traders, and missionaries was creative and adaptive. Intercultural commerce, communication, and religion encouraged different peoples to learn each other's languages, customs, and manners, so that new hybrid forms might build bridges between them. Such cultural borrowing and imitation defined the nature of European-Indian diplomacy in colonial Pennsylvania, which was constantly employed to extend trade, win converts, and keep the peace.

Throughout the colonial era, treaty conferences convened in locations like Philadelphia, Easton, Logstown, and Carlisle, where participants engaged in speech-making and gift exchange to advance their interests against one another. This process was seldom as peaceful or friendly as West depicted in Penn's Treaty with the Indians, but it did provide a basis for mutual understanding and communication so long as each party acted in good faith toward the other.

Indian Dispossession

Unfortunately, nothing eroded that good faith more severely than the Europeans' pursuit of Indian lands. The Dutch and the Swedes came in small numbers and primarily for trade, but after Penn's colony was established in 1682, droves of settlers recruited by the Penn family in Britain, Ireland, and Germany began arriving. By the early decades of the eighteenth century, this onslaught of newcomers was displacing Indians from the Delaware and lower Susquehanna valleys.

Indian dispossession was accelerated by the Penn family's desire for land. William Penn's heirs, who remained in England and tended to regard their colony as a real estate investment, relied on the Philadelphia merchant James Logan to conduct Indian affairs on their behalf. Logan profited handsomely from the fur trade and land sales, and never missed a chance to wheedle more territory out of Indian hands. During the 1730s and 1740s, he brought Pennsylvania into the Iroquois confederacy's Covenant Chain alliance with the British colonies.

The Iroquois, their homelands located in modern upstate New York, claimed to own most of Pennsylvania's frontier by right of conquest from the Delaware and Susquehannocks. Logan and other Pennsylvania officials were more than happy to recognize that claim, so long as the Iroquois remained willing to sell land to the Penn family. Locked out of this process were the actual inhabitants of the land in question, primarily Delaware and Shawnee who lived in the Delaware, Susquehanna, and Ohio-Allegheny valleys.

By the mid-1700s, the high-handed and fraudulent tactics employed by Logan and the Penn family in acquiring land had soured Indian relations within the colony. The infamous

The contest for land eroded the goodwill that go-betweens, traders, and missionaries relied on in conducting their affairs. During the 1750s, their efforts collapsed under the strain of war, unleashing unprecedented violence between Indians and colonists on the Pennsylvania frontier.