Chapter Five: Traveling by Rail - The Passenger Story

Before the arrival of railroads, people moved no faster than their feet or a horse could carry them. Travel across Pennsylvania -especially its many mountains - was slow, especially when winter snows, spring rains, and other inclement weather made dirt roads and woodland trails all but impassable. The construction of canals and a handful of paved roads, the first of which was Pennsylvania's own  Lancaster Turnpike, were tremendous improvements.

Lancaster Turnpike, were tremendous improvements.

After completion of the state-funded and owned Main Line of Public Works in 1834, an enormously expensive combination of canals and crude railroads, travelers could journey between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia in three-and-a-half to four-and-a-half days. In 1854, the coming of the all-rail Pennsylvania Railroad route shredded that time to thirteen hours and also cut the fare from $9.50 to $8.00. Within a decade, Pennsylvanians could - by taking connecting trains - travel to almost any spot in the state within a single day's time. So it was no wonder that, with its dense population and location as a crossroads between major cities, Pennsylvania became a leader in passenger railroading.

Main Line of Public Works in 1834, an enormously expensive combination of canals and crude railroads, travelers could journey between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia in three-and-a-half to four-and-a-half days. In 1854, the coming of the all-rail Pennsylvania Railroad route shredded that time to thirteen hours and also cut the fare from $9.50 to $8.00. Within a decade, Pennsylvanians could - by taking connecting trains - travel to almost any spot in the state within a single day's time. So it was no wonder that, with its dense population and location as a crossroads between major cities, Pennsylvania became a leader in passenger railroading.

The earliest public passenger railroad in Pennsylvania to serve a city was the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown (P G and N), which later became part of the Reading Railroad. Incorporated in 1831, it ran the seven miles from Philadelphia to Germantown with horses drawing the cars. By 1835, when it extended another ten miles to Norristown, it was running locomotives jauntily named Black Hawk, Samson, and Old Ironsides, the last being the first locomotive built by Philadelphia's Baldwin Locomotive Works. Despite the early crude accommodations, the PG&N offered dependable, smooth, all-weather service.

At first a novelty and a curiosity, rail travel in the 1830s and 1840s was uncomfortable and, at times, dangerous. Early railcars were stagecoach-like vehicles, or Spartan boxy cars like the Pennsylvania Coal Co. Railroad's "Pioneer". The crude suspension systems of early railroad cars did little to cushion the unevenness of equally crude tracks, which were usually made of iron straps fastened atop wooden stringers. This type of construction always posed the threat of "snake-heads," which occurred when the end of an iron strap under tension broke loose from the wood stringer and suddenly burst through the car floor, causing injury or even death. But Americans loved speed, and even the crudest trains pulled by the most basic steam engines could roll along at a lively thirty miles an hour.

"Pioneer". The crude suspension systems of early railroad cars did little to cushion the unevenness of equally crude tracks, which were usually made of iron straps fastened atop wooden stringers. This type of construction always posed the threat of "snake-heads," which occurred when the end of an iron strap under tension broke loose from the wood stringer and suddenly burst through the car floor, causing injury or even death. But Americans loved speed, and even the crudest trains pulled by the most basic steam engines could roll along at a lively thirty miles an hour.

The growth of passenger travel created a need for more comfortable cars that were created specifically for railroad use. In 1838, Cumberland Valley Railroad director

Cumberland Valley Railroad director  Philip Berlin commissioned the construction of the nation's first sleeping car, built by Philip Imlay of Philadelphia.

Philip Berlin commissioned the construction of the nation's first sleeping car, built by Philip Imlay of Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania passenger-car builders included Billmeyer and Small, which for decades manufactured passenger and freight cars for narrow-gauge railroads in York; American Car and Foundry of Berwick; and the Budd Co. of Philadelphia, which built streamlined passenger cars in the twentieth century.

As tracks lengthened, so did the journey times, which created a need for restaurants, hotels, and taverns, which often doubled as train stations. Like other great railroad hotels, Altoona's Logan House, built by the Pennsylvania Railroad, served as host for presidents and kings. As railroad travel became more accepted and more convenient, passengers began to use them for all kinds of travel - business, personal, and leisure. By the 1870s, Pennsylvania rail lines were running excursion trains to Niagara Falls, Atlantic City, Pocono resorts, and other leisure destinations, including

Logan House, built by the Pennsylvania Railroad, served as host for presidents and kings. As railroad travel became more accepted and more convenient, passengers began to use them for all kinds of travel - business, personal, and leisure. By the 1870s, Pennsylvania rail lines were running excursion trains to Niagara Falls, Atlantic City, Pocono resorts, and other leisure destinations, including  Williams Grove picnic park near Carlisle, site of the Pennsylvania Grange's annual fair. Indeed, railroads often promoted such parks in order to build Sunday, holiday, and vacation ridership.

Williams Grove picnic park near Carlisle, site of the Pennsylvania Grange's annual fair. Indeed, railroads often promoted such parks in order to build Sunday, holiday, and vacation ridership.

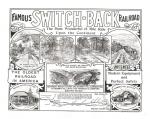

One of the nation's oldest coal lines, the Switchback Railroad, was reborn as a scenic railroad for tourists visiting the beautiful mountains of Carbon County, "The Switzerland of America." The breathtaking

Switchback Railroad, was reborn as a scenic railroad for tourists visiting the beautiful mountains of Carbon County, "The Switzerland of America." The breathtaking  Kinzua Viaduct in McKean County, a monument of railroad engineering, attracted tourists until its collapse into the gorge below in 2003.

Kinzua Viaduct in McKean County, a monument of railroad engineering, attracted tourists until its collapse into the gorge below in 2003.

The danger of train travel, and the great crashes that, over time, killed hundreds of people, both fascinated and horrified the American public. Pennsylvania suffered its share of horrible train wrecks, including the head-on collision that killed sixty Sunday school picnickers near Fort Washington on July 17, 1856, the infamous Pike County Civil War Prison Train wreck of 1864, and the September 6, 1943, derailment of the Congressional Limited, which killed seventy-eight passengers and a dining-car employee.

Civil War Prison Train wreck of 1864, and the September 6, 1943, derailment of the Congressional Limited, which killed seventy-eight passengers and a dining-car employee.

Train journeys were also the stuff of legends. Abraham Lincoln rode a special train from Washington, D.C., through Hanover Junction en route to delivering his famous Gettysburg Address, then traveled along that same line just two years later as a train carried his coffin on the president's final journey to his resting place in Springfield, Illinois.

Hanover Junction en route to delivering his famous Gettysburg Address, then traveled along that same line just two years later as a train carried his coffin on the president's final journey to his resting place in Springfield, Illinois.

By the 1870s, American railroads were vast, complex business operations that spread across the nation. At the center of the American Industrial Revolution, railroads collapsed time and space, bringing previously distant, isolated regions of the nation into close proximity. On the eve of the Civil War, it took more than two months to travel overland from Pittsburgh to San Francisco. By 1870, it took about five days. Railroads wove the previously distant states into a united nation.

To service the growing millions of passengers, railroads built thousands of stations, which ranged from small-town depots like PRR's Lewistown station to the massive and palatial Pennsylvania Station that the PRR opened in Manhattan in 1910. In Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania and Reading railroads each built stations to trumpet their own importance.

Lewistown station to the massive and palatial Pennsylvania Station that the PRR opened in Manhattan in 1910. In Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania and Reading railroads each built stations to trumpet their own importance.

The PRR opened its stone West Philadelphia Station in 1864, and the giant ten-story, gothic-fringed Broad Street Station, which served as company headquarters as well as a passenger depot, in 1881. Next came the Reading's Reading Terminal (1893), followed by the Pennsylvania's West Philadelphia station (1903), Reading's North Broad Street Station (1929), PRR's Suburban Station (1930) and PRR's

Reading Terminal (1893), followed by the Pennsylvania's West Philadelphia station (1903), Reading's North Broad Street Station (1929), PRR's Suburban Station (1930) and PRR's  Pennsylvania Station (1933, better known as 30th Street Station). Passengers traveled around and through Pennsylvania for many purposes and on many kinds of trains.

Pennsylvania Station (1933, better known as 30th Street Station). Passengers traveled around and through Pennsylvania for many purposes and on many kinds of trains.

Among the most luxurious trains catering to business travelers were those that made long-haul runs, traveling 300 to 1,000 miles. Some offered a library and smoking parlor, updated stock-market quotations and sports scores, and maid, stenographer, and barber service. Often running through the state on fast overnight schedules, they carried sleeping-car, dining-car, parlor-car, lounge-car, and observation-car accommodations. The richest travelers owned their own private cars, which were coupled at the tail end of many of the fastest and most exclusive trains.

The PRR ran its famous Broadway Limited between New York and Chicago via Philadelphia, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh; the New York Central linked the same endpoints with its swanky Twentieth Century Limited via Erie; and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's flagship was its Capitol Limited, linking New York, Philadelphia, and Washington to Chicago via Pittsburgh.

Regional rail lines introduced their own great passenger trains, including the Lackawanna's Phoebe Snow (New York-Buffalo via Scranton), the Lehigh Valley's Black Diamond (New York - Buffalo via Allentown and Wilkes-Barre), Pittsburgh and Lake Erie's Steel King (Pittsburgh - Youngstown - Cleveland), and the Reading's King Coal (Philadelphia - Shamokin) and Queen of the Valley (Philadelphia - Reading - Lebanon - Hershey - Harrisburg).

Urban rail systems enabled wealthy and middle-class city dwellers to escape the crowding and dirt of the state's booming industrial metropolises, and to move to the new railroad-corridor suburbs, like Bryn Mawr, that the rail lines and their investors were building along their tracks. In short, railroads fundamentally altered the way people chose how and where to live. Commuter trains on both the former Reading and PRR routes continue to serve Philadelphia-area residents today under the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority.

Bryn Mawr, that the rail lines and their investors were building along their tracks. In short, railroads fundamentally altered the way people chose how and where to live. Commuter trains on both the former Reading and PRR routes continue to serve Philadelphia-area residents today under the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority.

PRR electrified its Philadelphia commuter service, starting in 1914 with the Paoli Local, and the Reading followed suit in 1931. Commuters living along Pittsburgh's river valleys could ride PRR locals in five directions, the swankiest suburbs being Sewickley or Ligonier. B&O commuter trains were strictly workday affairs, serving Braddock and McKeesport. Pittsburgh and Lake Erie's trains served Aliquippa, Beaver, and Beaver Falls.

Railroads like the East Broad Top in Huntingdon County operated what amounted to blue-collar commuter runs – miners' trains for workers traveling to and from their jobs in the coal mines. By the early 1900s "locals," as they were called, covered nearly every inch of track in the state, stopping every mile or two to pick up or discharge mail, express packages, milk, small poultry, and people.

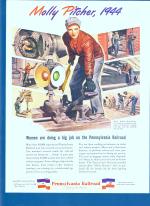

Passenger trains also were important during wars. During the Civil War, railroads carried troops and munitions to and from battle theaters, including Gettysburg, operated some of the first hospital trains for the combat-wounded, and carried Confederate prisoners of war to internment camps. During the twentieth century's two great world wars, the federal government pressed every available engine and car into service. In World War II, the United Service Organizations set up canteens at major PRR stations at Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Women volunteers staffed a trackside canteen at the B&O station in Connellsville, handing out free food, coffee, snacks, and cigarettes to thousands of servicemen. From 1941 to 1945, the PRR alone carried 17.5 million military personnel on troop trains.

Connellsville, handing out free food, coffee, snacks, and cigarettes to thousands of servicemen. From 1941 to 1945, the PRR alone carried 17.5 million military personnel on troop trains.

Interstate carriers were covered by federal rather than state law, but state laws still exerted a profound impact on railroad travel. For generations after the end of the Civil War, segregated seating on passenger trains in southern states made them a focus of African-American struggle against segregation. While Pennsylvania did not have Jim Crow laws to separate white and black passengers, Maryland's Jim Crow law, passed in 1904, forced the Cumberland Valley Railroad, among others, to maintain separate cars for African-American passengers, a practice that black passengers deeply resented. On CVRR's northbound trains headed from Hagerstown, Md., to Harrisburg, blacks at the first stop north of the Mason-Dixon Line, usually State Line, Greencastle, or Chambersburg, immediately relocated to the regular coaches. Maryland repealed its law in 1951, five years after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in interstate transportation in 1946.

From the 1850s to the 1920s, Americans relied heavily on passenger trains to carry them near and far. But with the coming of cheap, easily operated autos, paved roads, and limited-access highways, the first long-haul example of which was the Pennsylvania Turnpike, long-distance passenger trains became an endangered species. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought many cutbacks in passenger service, but it was also a time when railroads began to win back riders with air-conditioned cars and gleaming new stainless-steel streamliner trains, many of them built by the Budd Company in Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania Turnpike, long-distance passenger trains became an endangered species. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought many cutbacks in passenger service, but it was also a time when railroads began to win back riders with air-conditioned cars and gleaming new stainless-steel streamliner trains, many of them built by the Budd Company in Philadelphia.

Postwar prosperity brought auto ownership within reach of most American families. The end of tire and gas rationing, coupled with federal and state policymakers' decision to embark on a golden era of taxpayer-funded highway construction, ended the great passenger-train era. Railroads fought back with millions of dollars' worth of shiny diesel locomotives and modern equipment, but it wasn't enough. In 1957, the arrival of commercial jet aviation began to bring down the curtain. Eventually even the fastest train that travelled between New York and Chicago (15-3/4 hours) couldn't hope to compete with a Boeing 707 flight that took less than two hours. So the railroads gave up on long-distance passenger service and focused on freight.

The last privately operated long-haul passenger trains were discontinued on May 1, 1971, with the coming of Amtrak, the federally backed intercity rail passenger agency. Outside of the Northeast Corridor, service was cut to the bone or dropped. Pittsburgh, served by more than 370 departures a day in 1930, in 2004 had only six passenger trains. Only in the Northeast Corridor has passenger rail remained strong – Amtrak's Acela trains, which reach 150 mph on a short stretch of track in New England, the only high-speed trains in North America – serve Philadelphia thirty times a day. Philadelphia's regional commuter rail service remains one of the most extensive in the nation. In addition, Pennsylvania is home to a large number of tourist and scenic railroads that have sprung up since the 1960s.

After completion of the state-funded and owned

The earliest public passenger railroad in Pennsylvania to serve a city was the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown (P G and N), which later became part of the Reading Railroad. Incorporated in 1831, it ran the seven miles from Philadelphia to Germantown with horses drawing the cars. By 1835, when it extended another ten miles to Norristown, it was running locomotives jauntily named Black Hawk, Samson, and Old Ironsides, the last being the first locomotive built by Philadelphia's Baldwin Locomotive Works. Despite the early crude accommodations, the PG&N offered dependable, smooth, all-weather service.

At first a novelty and a curiosity, rail travel in the 1830s and 1840s was uncomfortable and, at times, dangerous. Early railcars were stagecoach-like vehicles, or Spartan boxy cars like the Pennsylvania Coal Co. Railroad's

The growth of passenger travel created a need for more comfortable cars that were created specifically for railroad use. In 1838,

Pennsylvania passenger-car builders included Billmeyer and Small, which for decades manufactured passenger and freight cars for narrow-gauge railroads in York; American Car and Foundry of Berwick; and the Budd Co. of Philadelphia, which built streamlined passenger cars in the twentieth century.

As tracks lengthened, so did the journey times, which created a need for restaurants, hotels, and taverns, which often doubled as train stations. Like other great railroad hotels, Altoona's

One of the nation's oldest coal lines, the

The danger of train travel, and the great crashes that, over time, killed hundreds of people, both fascinated and horrified the American public. Pennsylvania suffered its share of horrible train wrecks, including the head-on collision that killed sixty Sunday school picnickers near Fort Washington on July 17, 1856, the infamous Pike County

Train journeys were also the stuff of legends. Abraham Lincoln rode a special train from Washington, D.C., through

By the 1870s, American railroads were vast, complex business operations that spread across the nation. At the center of the American Industrial Revolution, railroads collapsed time and space, bringing previously distant, isolated regions of the nation into close proximity. On the eve of the Civil War, it took more than two months to travel overland from Pittsburgh to San Francisco. By 1870, it took about five days. Railroads wove the previously distant states into a united nation.

To service the growing millions of passengers, railroads built thousands of stations, which ranged from small-town depots like PRR's

The PRR opened its stone West Philadelphia Station in 1864, and the giant ten-story, gothic-fringed Broad Street Station, which served as company headquarters as well as a passenger depot, in 1881. Next came the Reading's

Among the most luxurious trains catering to business travelers were those that made long-haul runs, traveling 300 to 1,000 miles. Some offered a library and smoking parlor, updated stock-market quotations and sports scores, and maid, stenographer, and barber service. Often running through the state on fast overnight schedules, they carried sleeping-car, dining-car, parlor-car, lounge-car, and observation-car accommodations. The richest travelers owned their own private cars, which were coupled at the tail end of many of the fastest and most exclusive trains.

The PRR ran its famous Broadway Limited between New York and Chicago via Philadelphia, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh; the New York Central linked the same endpoints with its swanky Twentieth Century Limited via Erie; and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's flagship was its Capitol Limited, linking New York, Philadelphia, and Washington to Chicago via Pittsburgh.

Regional rail lines introduced their own great passenger trains, including the Lackawanna's Phoebe Snow (New York-Buffalo via Scranton), the Lehigh Valley's Black Diamond (New York - Buffalo via Allentown and Wilkes-Barre), Pittsburgh and Lake Erie's Steel King (Pittsburgh - Youngstown - Cleveland), and the Reading's King Coal (Philadelphia - Shamokin) and Queen of the Valley (Philadelphia - Reading - Lebanon - Hershey - Harrisburg).

Urban rail systems enabled wealthy and middle-class city dwellers to escape the crowding and dirt of the state's booming industrial metropolises, and to move to the new railroad-corridor suburbs, like

PRR electrified its Philadelphia commuter service, starting in 1914 with the Paoli Local, and the Reading followed suit in 1931. Commuters living along Pittsburgh's river valleys could ride PRR locals in five directions, the swankiest suburbs being Sewickley or Ligonier. B&O commuter trains were strictly workday affairs, serving Braddock and McKeesport. Pittsburgh and Lake Erie's trains served Aliquippa, Beaver, and Beaver Falls.

Railroads like the East Broad Top in Huntingdon County operated what amounted to blue-collar commuter runs – miners' trains for workers traveling to and from their jobs in the coal mines. By the early 1900s "locals," as they were called, covered nearly every inch of track in the state, stopping every mile or two to pick up or discharge mail, express packages, milk, small poultry, and people.

Passenger trains also were important during wars. During the Civil War, railroads carried troops and munitions to and from battle theaters, including Gettysburg, operated some of the first hospital trains for the combat-wounded, and carried Confederate prisoners of war to internment camps. During the twentieth century's two great world wars, the federal government pressed every available engine and car into service. In World War II, the United Service Organizations set up canteens at major PRR stations at Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Women volunteers staffed a trackside canteen at the B&O station in

Interstate carriers were covered by federal rather than state law, but state laws still exerted a profound impact on railroad travel. For generations after the end of the Civil War, segregated seating on passenger trains in southern states made them a focus of African-American struggle against segregation. While Pennsylvania did not have Jim Crow laws to separate white and black passengers, Maryland's Jim Crow law, passed in 1904, forced the Cumberland Valley Railroad, among others, to maintain separate cars for African-American passengers, a practice that black passengers deeply resented. On CVRR's northbound trains headed from Hagerstown, Md., to Harrisburg, blacks at the first stop north of the Mason-Dixon Line, usually State Line, Greencastle, or Chambersburg, immediately relocated to the regular coaches. Maryland repealed its law in 1951, five years after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in interstate transportation in 1946.

From the 1850s to the 1920s, Americans relied heavily on passenger trains to carry them near and far. But with the coming of cheap, easily operated autos, paved roads, and limited-access highways, the first long-haul example of which was the

Postwar prosperity brought auto ownership within reach of most American families. The end of tire and gas rationing, coupled with federal and state policymakers' decision to embark on a golden era of taxpayer-funded highway construction, ended the great passenger-train era. Railroads fought back with millions of dollars' worth of shiny diesel locomotives and modern equipment, but it wasn't enough. In 1957, the arrival of commercial jet aviation began to bring down the curtain. Eventually even the fastest train that travelled between New York and Chicago (15-3/4 hours) couldn't hope to compete with a Boeing 707 flight that took less than two hours. So the railroads gave up on long-distance passenger service and focused on freight.

The last privately operated long-haul passenger trains were discontinued on May 1, 1971, with the coming of Amtrak, the federally backed intercity rail passenger agency. Outside of the Northeast Corridor, service was cut to the bone or dropped. Pittsburgh, served by more than 370 departures a day in 1930, in 2004 had only six passenger trains. Only in the Northeast Corridor has passenger rail remained strong – Amtrak's Acela trains, which reach 150 mph on a short stretch of track in New England, the only high-speed trains in North America – serve Philadelphia thirty times a day. Philadelphia's regional commuter rail service remains one of the most extensive in the nation. In addition, Pennsylvania is home to a large number of tourist and scenic railroads that have sprung up since the 1960s.