Overview: The Railroad in Pennsylvania

"There are people now living in Pittsburgh who have traveled diligently for a whole week to reach Philadelphia. The same persons can now go from our city to the eastern metropolis between sunrise and sunset of a summer's day, without fatigue, and without occasion for stopping to eat more than one meal."

Daily Morning Post, Pittsburgh, on the opening of

the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1854.

Trains made Pennsylvania an industrial giant. And today, when a train rumbles by -whether it's a two-car freight on a rural line or the silvery, standing-room-only Paoli Local at rush hour - the state's railroading history is still being written. In Pennsylvania, railroading is not only alive but also thriving.

The symbols of the industry's rich past - the mournful sound of a steam-locomotive whistle, or banjo-plunking ballads about the lonely life of a brakeman - have been replaced by the daily marvel of fleets moving 10,000-ton coal trains out of the bituminous coalfields of Greene County to electric-generating stations across the Northeast. By the sight of intermodal trains, loaded with double-stacked cargo containers from the North Pacific and now slicing through Erie or Johnstown en route to the East Coast. Or by the sight of Amtrak's high-speed Acela train, capable of sprinting 150 miles an hour before gliding to a smooth stop at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia.

But the transition to the railroad revolution was many years in coming. Railroading started in the Keystone state nearly two centuries ago with a quarry tramway in Delaware County south of Philadelphia, near present-day Chester. Like all other railroads of that day, it relied on horses or mules for power. This and other early railways were but the dim ancestors of modern railroading. No faster than wagons or canal boats, their main virtue lay in their smooth-running rails, which were a significant improvement over rutted roads. Pennsylvania had no urgent reason to invest in railroad technology until 1825, when the Erie Canal linked New York City's ports to Midwest markets. Now this was a revolution.

Suddenly Pennsylvanians had to find a way to compete with New York and link their state to Midwestern markets. Harnessing the power of steam to create a movable form of propulsion first took place in Great Britain. It first arrived in the United States in 1829 when the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company imported the Stourbridge Lion, the first steam locomotive to operate in America, from England. But this and other early locomotives were too small and unreliable to move significant amounts of freight over the Allegheny Mountains.

Started in 1834, the state-owned Main Line of Public Works was an ingenious solution that used canal boats where possible on relatively level ground and a combination of gravity and stationary steam engines where necessary in the mountains. This patchwork of canals, railroads, and inclined planes offered a 3-1/2-day journey from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. But it was soon doomed by the coming of the cheaper, all-purpose, all-weather Pennsylvania Railroad.

Though canals continued to move substantial material within the state, faster, more versatile railroads soon took over the job of meeting most transportation needs. Railroads soon unlocked the raw materials with which Pennsylvania was blessed, allowing manufacturing to flourish. In 1844, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad became the first line in America to carry a million tons of freight in a year. In Pennsylvania and the rest of the nation, the industrial revolution rode on American rails. Trains carried coal and lumber to consumers quickly and cheaply. They hauled minerals to iron foundries and steel mills, then turned around and moved the finished metal to market.

Trains also raised the standard of living by cheaply transporting consumer goods and foodstuffs over long distances. Pennsylvania agriculture expanded as once-isolated regions populated by farmers now reached out via the rails to new markets. The invention of refrigerator cars brought Iowa beef, California lettuce, and Florida oranges to the East Coast. Passenger trains carried people and mail rapidly. And travelers began to use trains to travel for shopping, business, vacations, and, around cities, to commute to and from work.

During the Civil War, railroads moved troops and materiel to the front, and evacuated wounded soldiers to hospitals. After the war, the industry began to agree on standards, which included a uniform track gauge of 4 feet 8-1/2 inches between the rails, and couplers and other fittings needed to freely exchange cars among railroads. With these steps, railroads grew from regional feeder lines into a national network, an achievement that was capped by the driving of the Golden Spike on the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. The mileage of American railroads more than quintupled from 1860 to 1890, growing from 30,000 miles to almost 160,000.

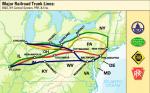

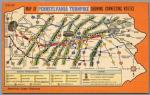

In this sprawling national network, Pennsylvania became a crossroads, with four major trunk lines linking the East Coast to western states (Pennsylvania Railroad, Baltimore and Ohio, New York Central, and Erie), and others linking Canada and northern states through Pittsburgh and Philadelphia to the states to the south. Founded in 1846 as purely an in-state line, the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad became the nation's single most important railroad, carrying 10 percent of all freight in America and 20 percent of all passengers. In 1880, with 30,000 employees and $400 million in capital, it was the nation's largest corporation.

Railroads even regulated the pace of life. Standard time zones, established by the railroads in 1883, replaced the fragmented system by which, as a PRR timetable once explained, "Philadelphia local time" is seven minutes faster than Harrisburg time, thirteen minutes faster than Altoona time, and nineteen minutes faster than Pittsburgh time."

Soon tens of thousands of men, and some women, worked both for the carriers and for supporting industries throughout Pennsylvania. These included firms that built locomotives, freight and passenger cars, air brakes, signals, and steel rails, and, of course, the suppliers of lumber and the raw iron and steel that went into making such items.

Railroads also brought about social change, and not always for the better. With hand brakes and old-fashioned link-and-pin couplers, work was so hazardous that many insurance companies refused to write policies for trainmen. The need for accident and death benefits led railroaders to organize their own benevolent mutual insurance brotherhoods. In time, they joined the emerging organized labor movement to counter the influence of capital. Fueled by labor unrest, a backlash against the railroads boiled over in strikes and riots in most Pennsylvania cities in 1877, sometimes with fatal results.

Railroads also changed the nature of work. Train crews were on call around the clock, so daily rhythms of eating and sleeping were continually disrupted. Maintaining a normal social life was nearly impossible. When they reached the end of their run over a division (usually 100 miles), crews were often stuck in that city on layovers, sometimes for days, waiting to work a train back to their home terminal. With time and money on their hands, and separated from family and home routines, some trainmen were easy prey for vices such as gambling, drinking, or prostitution.

Through both union rules and management preference, railroads also enforced ethnic and racial divisions. Menial jobs such as grading and laying track went first to Irish laborers, and later to Italians, Eastern Europeans, African Americans, and, during World War II, Mexicans. For blacks, other jobs were limited to locomotive firemen, coach cleaners, station janitors, redcaps, or dining-car waiters. Even the highest-ranking job for African-Americans -Pullman sleeping-car porter - was still a subservient position.

Women worked primarily as telegraphers or signal tower operators until World War I, when railroads hired them to replace men who joined the military. Soon they were working as full-time clerks, secretaries, and ticket agents. By the early 1950s, the Pennsylvania Railroad boasted that it employed several women lawyers in its legal department.

Railroads built civil engineering and architectural landmarks in Pennsylvania's cities and countryside (including probably the most widely known - Horseshoe Curve near Altoona), and stations, bridges, and tunnels in every part of the state. U.S. railroad mileage peaked in 1916 at 254,000 miles; Pennsylvania's mileage topped out at 11,500.

With the coming of publicly funded highways and the availability of automobiles, railroads began a long downward slide after World War II. Two mid-sized regional railroads in Pennsylvania were among the first line-haul carriers to be abandoned nationally - the Pittsburgh, Shawmut and Northern in 1948 (190 miles) and the New York, Ontario and Western in 1957 (547 miles). Nearly every major line in Pennsylvania failed in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Penn Central (successor to PRR), Erie Lackawanna, Reading, Jersey Central, Lehigh Valley, and Lehigh and Hudson River railroads all went bankrupt, and Baltimore and Ohio nearly did so. To preserve essential freight and passenger service, Congress created new corporations to take over intercity rail passenger service (Amtrak, in 1971) and northeastern freight service (Conrail, in 1976, took over PC, EL, Reading, Jersey Central, Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines (a minor New Jersey subsidiary of PC and Reading, LV, and L and HR). With regulatory reforms, the ability to set prices in a freer market, and the help of labor concessions, Conrail in 1987 returned to the private sector, and, more importantly, to profitability. Its key location made it a desirable plum for other Eastern carriers and in 1999 it was split up and sold to CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Corporation for $10 billion.