Chapter One: Study and Supply

Imagine the "Want Ad" that President Thomas Jefferson might have published in 1803 as he began his search for someone to lead his proposed expedition to the Pacific Ocean:

In fact, Jefferson sought an American Renaissance man who would be "perfectly skilled in botany, natural history, mineralogy, astronomy, with at the same time the necessary firmness of body and mind, habits of living in the woods and familiarity with the Indian character." Unfortunately, no single American embodied all of these skills and traits. So Jefferson selected the smartest, most seasoned frontiersman he knew: Meriwether Lewis. And then he promptly sent Lewis to Pennsylvania to acquire the additional training and knowledge in botany, natural history, astronomy, and medicine that was necessary for this arduous mission.

Meriwether Lewis. And then he promptly sent Lewis to Pennsylvania to acquire the additional training and knowledge in botany, natural history, astronomy, and medicine that was necessary for this arduous mission.

At Jefferson's request, Meriwether Lewis first traveled to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to meet with Andrew Ellicott, a brilliant and adventurous Bucks County surveyor and mapmaker who served in the Revolution, planned Washington, D.C., and made the first topographical study of Niagara Falls. Lewis spent two and a half weeks with Ellicott in late April and early May 1803, learning everything he could about frontier surveying.

Andrew Ellicott, a brilliant and adventurous Bucks County surveyor and mapmaker who served in the Revolution, planned Washington, D.C., and made the first topographical study of Niagara Falls. Lewis spent two and a half weeks with Ellicott in late April and early May 1803, learning everything he could about frontier surveying.

After studying with Ellicott, Jefferson's instructions to Lewis were very clear: Go to Philadelphia and consult with the nation's best and brightest scientists, naturalists, and mathematicians, all professors at the University of Pennsylvania. These men included

Jefferson's instructions to Lewis were very clear: Go to Philadelphia and consult with the nation's best and brightest scientists, naturalists, and mathematicians, all professors at the University of Pennsylvania. These men included  Benjamin Smith Barton, who guided Lewis on what plants to collect, as well as how to safeguard and annotate them; mathematician

Benjamin Smith Barton, who guided Lewis on what plants to collect, as well as how to safeguard and annotate them; mathematician  Robert Patterson, who added to Lewis' recent studies with Ellicott by tutoring Lewis in an art now known as "global positioning";

Robert Patterson, who added to Lewis' recent studies with Ellicott by tutoring Lewis in an art now known as "global positioning";  Dr. Benjamin Rush, who helped Lewis learn about Indian languages and cultures, and gave him instructions on diet, health, and medicine, as well as advice and remedies for daily discomforts; and paleontologist

Dr. Benjamin Rush, who helped Lewis learn about Indian languages and cultures, and gave him instructions on diet, health, and medicine, as well as advice and remedies for daily discomforts; and paleontologist  Caspar Wistar, who suggested that some very particular pre-historic finds in natural history might be useful to science.

Caspar Wistar, who suggested that some very particular pre-historic finds in natural history might be useful to science.

All these men were also fellow members of the American Philosophical Society, a group of curious, collegial, and collaborative intellectuals committed to disseminating "useful knowledge." In 1803, Jefferson was also president of the Society. Not long after Lewis left on the expedition, the Society elected him as a member.

In May 1803, Philadelphia was a thriving city of red brick houses and straight streets, fueled by commerce from its thriving port and emerging industrial economy. The city was in the midst of an economic and a cultural boom, and its population of 81,000 was on the rise. Here too, could be found the nation's first natural history museum, which founder Charles Willson Peale had recently moved from Philosophical Hall to the much larger second floor of Independence Hall.

Charles Willson Peale had recently moved from Philosophical Hall to the much larger second floor of Independence Hall.

In addition to studying in Philadelphia, Lewis also bought supplies for the expedition. Israel Whelan served as Lewis' local purchasing agent, filling Lewis' long list of specialty needs by searching the shelves and storerooms of at least twenty-eight shops owned by Philadelphia's merchants and artisan manufacturers. These purchases - in addition to those from the new Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia and the arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia - had to keep the members of the proposed expedition alive, if not comfortable, as they traversed the continent.

Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia and the arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia - had to keep the members of the proposed expedition alive, if not comfortable, as they traversed the continent.

What did they buy? At the arsenals, Lewis obtained weapons and clothing. From the merchants, he purchased large sheets of oiled linen, waterproofing to protect supplies, mosquito netting to protect his crew, whiskey to reward them, and portable soup consisting of a boiled down paste of beef, eggs and vegetables to feed them. In all, Lewis' Philadelphia purchases filled thirty-five boxes, each weighing one hundred pounds.

Were there mistakes made in the purchase of supplies? No doubt. The Expedition ran out of blue beads to give to the Native Americans, and the three thermometers Lewis purchased broke before they arrived at the Rockies. The single most expensive purchase - an exceptionally accurate $250 clock known as a chronometer - also turned out to be one of the best. Ellicott and Patterson had agreed with one another (and disagreed with Jefferson) on how Lewis should collect the accurate celestial data needed to make maps, one of the expedition's primary objectives.

Ellicott and Patterson recommended that Lewis take a sextant, a surveyor's compass, and a chronometer, which Lewis bought from Thomas Parker in Philadelphia. When they began to teach Lewis how to use the new chronometer, his team of mentors found that the instrument was slow and out of register. Still confident that it was the best instrument, Benjamin Smith Barton carefully wound its works, stopped them by inserting a hog's bristle into its gears, packed it with the key and a screwdriver, and shipped it off to Andrew Ellicott in Lancaster. In Ellicott's confident hands, the chronometer was properly regulated, tested, and returned to Lewis.

While it appears that no single American possessed all the requisite skills and experience to conduct a successful expedition to the Pacific and back, the young nation collectively possessed the talents, insights, experience, and skills necessary to launch such a trip. One of the best examples of the collaborative culture was the decision to use, train, test, repair, and ultimately to make daily use of the chronometer from Philadelphia.

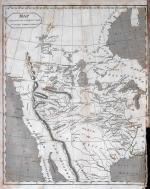

Two hundred years later, we can judge the impact of this collective decision by looking at one product from the expedition: the map produced from the data Lewis and Clark collected. This document, based on Clark's hand-drawn map and engraved in Philadelphia by Samuel Lewis, not only changed the shape of the nation; it became one of the most important, interesting, and accurate maps in the history of cartography.

Wanted - Experienced expedition leader in top physical condition to pave the way for America's expansion. Must be able to survive 8,000 miles of uncharted, dangerous territory for two years or more while collecting data for precise mapping, and useful and interesting plants and animals. Military experience on the frontier and excellent diplomatic and writing skills required. Medical knowledge and academic experience abroad preferred.

In fact, Jefferson sought an American Renaissance man who would be "perfectly skilled in botany, natural history, mineralogy, astronomy, with at the same time the necessary firmness of body and mind, habits of living in the woods and familiarity with the Indian character." Unfortunately, no single American embodied all of these skills and traits. So Jefferson selected the smartest, most seasoned frontiersman he knew:

At Jefferson's request, Meriwether Lewis first traveled to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to meet with

After studying with Ellicott,

All these men were also fellow members of the American Philosophical Society, a group of curious, collegial, and collaborative intellectuals committed to disseminating "useful knowledge." In 1803, Jefferson was also president of the Society. Not long after Lewis left on the expedition, the Society elected him as a member.

In May 1803, Philadelphia was a thriving city of red brick houses and straight streets, fueled by commerce from its thriving port and emerging industrial economy. The city was in the midst of an economic and a cultural boom, and its population of 81,000 was on the rise. Here too, could be found the nation's first natural history museum, which founder

In addition to studying in Philadelphia, Lewis also bought supplies for the expedition. Israel Whelan served as Lewis' local purchasing agent, filling Lewis' long list of specialty needs by searching the shelves and storerooms of at least twenty-eight shops owned by Philadelphia's merchants and artisan manufacturers. These purchases - in addition to those from the new

What did they buy? At the arsenals, Lewis obtained weapons and clothing. From the merchants, he purchased large sheets of oiled linen, waterproofing to protect supplies, mosquito netting to protect his crew, whiskey to reward them, and portable soup consisting of a boiled down paste of beef, eggs and vegetables to feed them. In all, Lewis' Philadelphia purchases filled thirty-five boxes, each weighing one hundred pounds.

Were there mistakes made in the purchase of supplies? No doubt. The Expedition ran out of blue beads to give to the Native Americans, and the three thermometers Lewis purchased broke before they arrived at the Rockies. The single most expensive purchase - an exceptionally accurate $250 clock known as a chronometer - also turned out to be one of the best. Ellicott and Patterson had agreed with one another (and disagreed with Jefferson) on how Lewis should collect the accurate celestial data needed to make maps, one of the expedition's primary objectives.

Ellicott and Patterson recommended that Lewis take a sextant, a surveyor's compass, and a chronometer, which Lewis bought from Thomas Parker in Philadelphia. When they began to teach Lewis how to use the new chronometer, his team of mentors found that the instrument was slow and out of register. Still confident that it was the best instrument, Benjamin Smith Barton carefully wound its works, stopped them by inserting a hog's bristle into its gears, packed it with the key and a screwdriver, and shipped it off to Andrew Ellicott in Lancaster. In Ellicott's confident hands, the chronometer was properly regulated, tested, and returned to Lewis.

While it appears that no single American possessed all the requisite skills and experience to conduct a successful expedition to the Pacific and back, the young nation collectively possessed the talents, insights, experience, and skills necessary to launch such a trip. One of the best examples of the collaborative culture was the decision to use, train, test, repair, and ultimately to make daily use of the chronometer from Philadelphia.

Two hundred years later, we can judge the impact of this collective decision by looking at one product from the expedition: the map produced from the data Lewis and Clark collected. This document, based on Clark's hand-drawn map and engraved in Philadelphia by Samuel Lewis, not only changed the shape of the nation; it became one of the most important, interesting, and accurate maps in the history of cartography.