Chapter Three: Pennsylvania 1820-1865: Expansion and Reforms

In the mid-1800s, the United States and Pennsylvania, its second most populous state, continued to experience rapid and revolutionary physical, economic, political, social, and cultural transformations. Between the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and end of the Mexican American War in 1848, the nation more than tripled in size. Pennsylvanians, like other Americans, were drawn to the West. Seven of the thirty-five men who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their great trip across the continent were Pennsylvania frontiersmen, including  Patrick Gass, who wrote the first account of the Expedition of Discovery, published in Pittsburgh in 1807.

Patrick Gass, who wrote the first account of the Expedition of Discovery, published in Pittsburgh in 1807.

In the early 1800s, ornithologist John James Audubon and botanist William Baldwin, zoologist Thomas Say, and other Pennsylvania scientists helped document the flora, fauna, and geology of the nation’s vast interior. In his Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians (1841),

John James Audubon and botanist William Baldwin, zoologist Thomas Say, and other Pennsylvania scientists helped document the flora, fauna, and geology of the nation’s vast interior. In his Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians (1841),  George Catlin provided the nation gorgeously rendered paintings of the Indian tribes of the Great Plains and reported detailed descriptions of their daily lives.

George Catlin provided the nation gorgeously rendered paintings of the Indian tribes of the Great Plains and reported detailed descriptions of their daily lives.

At home, botanists William Darlington and other Pennsylvania naturalists continued to engage in groundbreaking work. Charles Darwin’s thoughts on the evolution of species were deeply influenced by the work of zoologist

William Darlington and other Pennsylvania naturalists continued to engage in groundbreaking work. Charles Darwin’s thoughts on the evolution of species were deeply influenced by the work of zoologist  Samuel S. Haldeman and supported by the physical evidence uncovered and explained by Philadelphia’s pioneering paleontologist,

Samuel S. Haldeman and supported by the physical evidence uncovered and explained by Philadelphia’s pioneering paleontologist,  Edward Drinker Cope. In the late 1800s, armchair adventurers would delight in the Adirondack Mountain canoe adventures and the practical advice on camping and other woodcraft written by Wellsboro’s

Edward Drinker Cope. In the late 1800s, armchair adventurers would delight in the Adirondack Mountain canoe adventures and the practical advice on camping and other woodcraft written by Wellsboro’s  George Washington Sears.

George Washington Sears.

The people of the Commonwealth and the nation continued to grapple with persistent questions about religion, race, ethnicity, gender, wealth and poverty, the meaning of the Constitution, and the nature of the America. In the 1800s, Pennsylvania remained a center of religious fervor and publication. It was in Cambria County, in 1814, that Father Demitrius Gallitizin published his eloquent and influential defense of the Catholic Church. A decade later, the Angel Moroni delivered to

Father Demitrius Gallitizin published his eloquent and influential defense of the Catholic Church. A decade later, the Angel Moroni delivered to  Joseph Smith, then living on a farm in Susquehanna County, the golden plates that make up the Book of Mormon. In the 1840s,

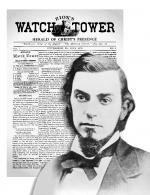

Joseph Smith, then living on a farm in Susquehanna County, the golden plates that make up the Book of Mormon. In the 1840s,  Isaac Leeser made Philadelphia the center of Hebrew printing and Jewish thought in America. And it was in Pittsburgh, in 1879, that Charles Taze Russell first published Zion's Watch Tower and Herald of Christ's Presence, the religious journal of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Isaac Leeser made Philadelphia the center of Hebrew printing and Jewish thought in America. And it was in Pittsburgh, in 1879, that Charles Taze Russell first published Zion's Watch Tower and Herald of Christ's Presence, the religious journal of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The Quaker spirit of reform that began with William Penn and led the campaign that brought an end to slavery in the northern states during the era of the American Revolution continued to burn brightly in the 1800s in the struggles against slavery, for better treatment of people in poverty and with mental illnesses, for the transformation of American prisons that simply detained people into penitentiaries dedicated to the reformation of their character, and in the campaign for women’s rights.

The first major East Coast city north of the Mason Dixon Line, Philadelphia was home to the nation’s first abolition society and a major center of the Underground Railroad. Here in 1833,

abolition society and a major center of the Underground Railroad. Here in 1833,  Lucretia C. Mott helped organize the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and here, in 1838, poet John Greenleaf Whittier, still young and unknown outside of abolitionist circles, was editing the abolitionist newspaper started by Quaker Benjamin Lundy when a white mob burned down the just-opened abolitionist meeting place

Lucretia C. Mott helped organize the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and here, in 1838, poet John Greenleaf Whittier, still young and unknown outside of abolitionist circles, was editing the abolitionist newspaper started by Quaker Benjamin Lundy when a white mob burned down the just-opened abolitionist meeting place  Pennsylvania Hall Here,

Pennsylvania Hall Here,  William Still, secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, wrote down the accounts of escaped slaves that in 1872 he would publish as The Underground Railroad, the greatest collection of slave narratives ever compiled. Excluded from full participation in the abolition movement because of her sex, Lucretia Mott would become a guiding light of the women’s suffrage movement, a campaign in which she would be joined in the 1860s by African-American writer

William Still, secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, wrote down the accounts of escaped slaves that in 1872 he would publish as The Underground Railroad, the greatest collection of slave narratives ever compiled. Excluded from full participation in the abolition movement because of her sex, Lucretia Mott would become a guiding light of the women’s suffrage movement, a campaign in which she would be joined in the 1860s by African-American writer  Frances Harper, who settled in Philadelphia in the 1860s.

Frances Harper, who settled in Philadelphia in the 1860s.

By the 1830s, Pittsburgh, too, its presses already buzzing, was emerging as a center of reform. Here, in the 1840s, black abolitionist Martin Delany published The Mystery before moving to Rochester, New York, to help Frederick Douglass start the North Star. Here, too,

Martin Delany published The Mystery before moving to Rochester, New York, to help Frederick Douglass start the North Star. Here, too,  Jane Grey Swisshelm became the first American woman to publish and edit an abolitionist journal. Swisshelm and Lucretia Mott in Philadelphia would lead the charge that compelled the Pennsylvania legislature in 1848 to pass the legislation that for the first time enabled women in Pennsylvania to retain the property they possessed upon entering a marriage. In Pittsburgh, native son

Jane Grey Swisshelm became the first American woman to publish and edit an abolitionist journal. Swisshelm and Lucretia Mott in Philadelphia would lead the charge that compelled the Pennsylvania legislature in 1848 to pass the legislation that for the first time enabled women in Pennsylvania to retain the property they possessed upon entering a marriage. In Pittsburgh, native son  Stephen Foster poured out the words and melodies that made him America’s most popular songwriter.

Stephen Foster poured out the words and melodies that made him America’s most popular songwriter.

In the middle decades of the 1800s, Philadelphia remained the nation’s second largest city. The city ceased to be the center of political debate after the nation’s capital moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800, and New York surpassed it as the nation’s commercial center by the 1820s. The city, however, remained a center of American theater and publishing. A brilliant actor who had made a small fortune by his early twenties, Edwin Forrest advanced American drama by using his reputation and money to offer prizes for the best plays written by American authors, including Philadelphian John Augustus Stone’s "Metamora, or the last of the Wampanoags," and Philadelphia physician Robert Montgomery Bird’s "The Gladiator," both of which Forrest delighted in performing for decades to come.

Edwin Forrest advanced American drama by using his reputation and money to offer prizes for the best plays written by American authors, including Philadelphian John Augustus Stone’s "Metamora, or the last of the Wampanoags," and Philadelphia physician Robert Montgomery Bird’s "The Gladiator," both of which Forrest delighted in performing for decades to come.

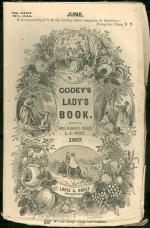

Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette was revived in the early 1820s as The Saturday Evening Post. By 1827 it boasted a weekly circulation of more than 7,000 copies by offering a mix of leading English and American writers. The Post’s success encouraged others to try their hand at magazine publishing, the most successful of whom were Louis Godey and George Rex Graham. A newcomer from New York, Godey issued the first number of his "Lady’s Book" in 1830.

Under the direction of Sarah Josepha Hale, who moved from Boston to Philadelphia in 1841, Godey’s Ladies Magazine became the leading women’s magazine in the country. Godey’s included steel engravings of the latest fashions in England and France—the original "fashion plates"—and employed leading writers, including T.S. Arthur, "Grace Greenwood," Harriett Beecher Stowe, Edgar Allan Poe, and other luminaries. By the 1850s, Godey’s was America’s most expensive magazine to produce, "a proud monument reared by the Ladies of America as a testimony of their worth."

"Grace Greenwood," Harriett Beecher Stowe, Edgar Allan Poe, and other luminaries. By the 1850s, Godey’s was America’s most expensive magazine to produce, "a proud monument reared by the Ladies of America as a testimony of their worth."

For American men, Philadelphia offered Graham’s Magazine, the most popular national literary periodical of its day. Conceding "the Julianas and Florellas of Feebledom" to Godey’s and Peterson’s Magazine—also published in Philadelphia for a national female audience—Graham worked to build a native American literature and a magazine worthy of a place "on the parlor table of every gentleman in the United States" by offering good pay to the best writers and poets from Philadelphia and throughout the nation, including Longfellow, J. Bayard Taylor, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Poe, who worked as an editor for the magazine from 1840 to 1842. Graham also employed English engraver John Sartain to provide mezzotints of a quality unparalleled in any other American magazine of the time.

Anchored by Godey’s and Graham’s, Philadelphia drew publishers, editors, writers, and engravers from elsewhere in United States and abroad, and became the center of a thriving literary scene. There, in the 1844, the ill-fated novelist George Lippard gave shape to the American Gothic novel in his lurid The Quaker City. And there, in 1852, T.S. Arthur wrote and published

The Quaker City. And there, in 1852, T.S. Arthur wrote and published  Ten Nights in a Bar Room, which fueled the American temperance movement by demonizing alcohol in much the same way that Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom's Cabin, first published the same year, enflamed American readers against slavery. These two books were the nation’s leading bestsellers in the 1850s.

Ten Nights in a Bar Room, which fueled the American temperance movement by demonizing alcohol in much the same way that Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom's Cabin, first published the same year, enflamed American readers against slavery. These two books were the nation’s leading bestsellers in the 1850s.

Philadelphia’s more than 100-year reign as the nation’s magazine publishing center ended by the 1860s, by which time it had been surpassed by New York. Graham’s went under in the late 1850s. Godey's would print its last issue in 1878, after a forty-eight–year run. The city remained a significant publishing center, however, especially for medical and scientific works, literary collections, encyclopedias, and works by African-American writers. Founded in 1838, the A.M.E. (African American Episcopal) Book Concern for decades was the nation’s largest publisher of African-American authors. Launched in 1868 by Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott and Company, Lippincott’s Magazine in 1890 became the first magazine to introduce Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes to American readers.

In the 1890s, Philadelphia again became an important center of American magazine publishing through the Curtis Publishing Company, whose Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Evening Post went on to become two of the most popular and successful magazines in American periodical history. Small magazines, almanacs, and newspapers also continued to thrive in cities and towns across the Commonwealth, including

Curtis Publishing Company, whose Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Evening Post went on to become two of the most popular and successful magazines in American periodical history. Small magazines, almanacs, and newspapers also continued to thrive in cities and towns across the Commonwealth, including  The Grit, published in Williamsport, PA, which in the early 1900s was the most widely distributed country and small-town weekly in the nation.

The Grit, published in Williamsport, PA, which in the early 1900s was the most widely distributed country and small-town weekly in the nation.

In the early 1800s, ornithologist

At home, botanists

The people of the Commonwealth and the nation continued to grapple with persistent questions about religion, race, ethnicity, gender, wealth and poverty, the meaning of the Constitution, and the nature of the America. In the 1800s, Pennsylvania remained a center of religious fervor and publication. It was in Cambria County, in 1814, that

The Quaker spirit of reform that began with William Penn and led the campaign that brought an end to slavery in the northern states during the era of the American Revolution continued to burn brightly in the 1800s in the struggles against slavery, for better treatment of people in poverty and with mental illnesses, for the transformation of American prisons that simply detained people into penitentiaries dedicated to the reformation of their character, and in the campaign for women’s rights.

The first major East Coast city north of the Mason Dixon Line, Philadelphia was home to the nation’s first

By the 1830s, Pittsburgh, too, its presses already buzzing, was emerging as a center of reform. Here, in the 1840s, black abolitionist

In the middle decades of the 1800s, Philadelphia remained the nation’s second largest city. The city ceased to be the center of political debate after the nation’s capital moved to Washington, D.C., in 1800, and New York surpassed it as the nation’s commercial center by the 1820s. The city, however, remained a center of American theater and publishing. A brilliant actor who had made a small fortune by his early twenties,

Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette was revived in the early 1820s as The Saturday Evening Post. By 1827 it boasted a weekly circulation of more than 7,000 copies by offering a mix of leading English and American writers. The Post’s success encouraged others to try their hand at magazine publishing, the most successful of whom were Louis Godey and George Rex Graham. A newcomer from New York, Godey issued the first number of his "Lady’s Book" in 1830.

Under the direction of Sarah Josepha Hale, who moved from Boston to Philadelphia in 1841, Godey’s Ladies Magazine became the leading women’s magazine in the country. Godey’s included steel engravings of the latest fashions in England and France—the original "fashion plates"—and employed leading writers, including T.S. Arthur,

For American men, Philadelphia offered Graham’s Magazine, the most popular national literary periodical of its day. Conceding "the Julianas and Florellas of Feebledom" to Godey’s and Peterson’s Magazine—also published in Philadelphia for a national female audience—Graham worked to build a native American literature and a magazine worthy of a place "on the parlor table of every gentleman in the United States" by offering good pay to the best writers and poets from Philadelphia and throughout the nation, including Longfellow, J. Bayard Taylor, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Poe, who worked as an editor for the magazine from 1840 to 1842. Graham also employed English engraver John Sartain to provide mezzotints of a quality unparalleled in any other American magazine of the time.

Anchored by Godey’s and Graham’s, Philadelphia drew publishers, editors, writers, and engravers from elsewhere in United States and abroad, and became the center of a thriving literary scene. There, in the 1844, the ill-fated novelist George Lippard gave shape to the American Gothic novel in his lurid

Philadelphia’s more than 100-year reign as the nation’s magazine publishing center ended by the 1860s, by which time it had been surpassed by New York. Graham’s went under in the late 1850s. Godey's would print its last issue in 1878, after a forty-eight–year run. The city remained a significant publishing center, however, especially for medical and scientific works, literary collections, encyclopedias, and works by African-American writers. Founded in 1838, the A.M.E. (African American Episcopal) Book Concern for decades was the nation’s largest publisher of African-American authors. Launched in 1868 by Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott and Company, Lippincott’s Magazine in 1890 became the first magazine to introduce Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes to American readers.

In the 1890s, Philadelphia again became an important center of American magazine publishing through the

![George Lippard, head and shoulders portrait, facing left] George Lippard, head and shoulders portrait, facing left]](cache/small/1-2-1EA9-25-ExplorePAHistory-a0n0y6-a_349.jpg)