Chapter Two: Writers and Publishers of the New Republic

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 concluded the American Revolutionary War and confirmed the independence of the United States. In the decades that followed, the new nation and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania would struggle through difficult growing pains, including the contentious framing of a second national and state constitution, internal rebellions, a prolonged and internally divisive undeclared war with both England and France, the rise of political parties, Indian wars, and a second short but bloody war with Great Britain.

Pennsylvanians who lived through the world-shaking events of the 1770s and 1780s faced the great challenge of securing independence and forging of a new nation. The United States Constitution, framed in Philadelphia, was not accepted without a struggle. It was Pennsylvanians William Findley and

William Findley and  Robert Whitehill, two of the Constitution's principal opponents, whose fifteen objections began the debate that led to the creation of a Bill of Rights.

Robert Whitehill, two of the Constitution's principal opponents, whose fifteen objections began the debate that led to the creation of a Bill of Rights.

In the decades that followed, a task of equal importance was to memorialize the struggles and principles upon which the nation had been founded. More memorials, histories, and other books and magazines came out of Philadelphia, the publishing center of the nation, than any other city. The first major history of the American Revolution, written by David Ramsay was published in Philadelphia in 1789.

David Ramsay was published in Philadelphia in 1789.

The first best-selling biography, "Parson" Mason Weems's Life of Washington, was first printed in extended form by Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey of Philadelphia, for whom Weems worked as a salesman. In it, Weems included the famous story about the cherry tree and otherwise played fast and loose with the historical truth. Published in Philadelphia in 1796, William Findley's History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania in the Year 1794 provided Americans the first book-length account of the Whiskey Rebellion, a history written from the perspective of the Whiskey Rebels rather than the federal government that had suppressed it.

The orations and essays of women, too, were published to convince females that their role as republican citizens required them to be virtuous educators of the next generation. Some women, however, went beyond what the men had hoped would be their "sphere" and demanded political rights as well.

Philadelphia was the political capitol of the United States until 1800, but well into the nineteenth century it remained the "Athens of America"-the nation's scientific, literary, and artistic center. Here in the 1790s, as the new United States struggled to remain neutral in the war between Revolutionary France and Great Britain and its monarchist allies, the thoughtfulness and eloquence of the Revolutionary generation gave way to political journalists whose sniping partisanship and personal nastiness fueled the fires of America's first political parties: the pro-French Democratic-Republicans, and pro-English Federalists. This first generation of political journalists included native Pennsylvanians and newcomers.

On the Federalist side were John Fenno, who brought his Gazette of the United States down from New York to become the unofficial publication of the ruling party; the prickly tongued "Peter Porcupine," the pen name of English expatriate William Cobbett; and "Oliver Oldschool Jr," the Bostonian Joseph Dennie, charged in 1803 with seditious libel for his scathing attacks on Thomas Jefferson.

Prominent writers for the Democratic-Republicans included Irish-born Federalist-turned-Jeffersonian Mathew Carey, a staunch defender of a strong American navy; New Yorker Philip Freneau, who was also one of the nation's most celebrated poets; Joseph Priestley, the world-famous scientist who had been driven out of England for his outspoken support of the French Revolution only to become a thorn in the side of President Adams in America; and Benjamin Franklin's grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache, who published his acid-tongued Philadelphia Aurora on his grandfather's printing press. Bache would be prosecuted and jailed under the Sedition Act of 1798, a law passed some said to curb the rants of "Lightning Rod Junior."

Joseph Priestley, the world-famous scientist who had been driven out of England for his outspoken support of the French Revolution only to become a thorn in the side of President Adams in America; and Benjamin Franklin's grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache, who published his acid-tongued Philadelphia Aurora on his grandfather's printing press. Bache would be prosecuted and jailed under the Sedition Act of 1798, a law passed some said to curb the rants of "Lightning Rod Junior."

While the city's journals inflamed passions in their full-bore attempts to sway public opinion, its printers were releasing a wealth of other publications. American magazine culture had been centered in Philadelphia since Benjamin Franklin began publication of the General Magazine in the early 1740s. From the 1780s onwards, a new generation of magazines committed to "public instruction and amusement," including The Port Folio, Columbian Magazine, and The American Museum, featured eclectic offerings of material from Europe and the United States for American readers. These included the satires, essays, the songs of Philadelphian Francis Hopkinson and the patriotic poems of Philip Freneau.

In their own attempts to make sense of what was taking place in the new nation, America's first novelists sold their books. The first bestseller was Susanna Rowson's Charlotte Temple (1790 or 1791), in which a damsel in distress suffers both physical and psychological torment. The first American to try to earn his living as a novelist (without much success) was Charles Brockden Brown, Philadelphia publisher of the short-lived Literary Magazine. In his groundbreaking novels illustrating "some important branches of the moral constitution of man"- Wieland (1798), Ormond (1799), Edgar Huntly (1799), and Arthur Mervyn (1799)- Brown created the overwrought concoctions of murder, seduction and romance, disease, and multiple forms of gothic terror, making Philadelphia the birthplace of American Gothic fiction and presenting a very different version of the world from contemporaries' optimistic hopes that a virtuous republic could solve many of humankind's problems.

Brown's brand of Gothic fiction would soon become associated with Philadelphia through the works of Robert Montgomery Bird and George Lippard. They, in turn, would influence writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe on to Stephen King and other current literary masters of horror.

In western Pennsylvania, Hugh Henry Brackenridge, founder of the Pittsburgh Gazette, also turned his pen to fiction. His Modern Chivalry (1792-1815) is a sprawling satire of life on the new republic's Pennsylvania frontier in which Captain Farrago, a would-be aristocrat, and his henchman Teague reprise the adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as a gullible populace is taken in by their attempts to gain political power.

Pittsburgh Gazette, also turned his pen to fiction. His Modern Chivalry (1792-1815) is a sprawling satire of life on the new republic's Pennsylvania frontier in which Captain Farrago, a would-be aristocrat, and his henchman Teague reprise the adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as a gullible populace is taken in by their attempts to gain political power.

Philadelphia was also the center of technological industrial innovations explained in pages of magazines and books published in the city. Following passage of the Patent Act of 1790, the American Philosophical Society served as the nation's first patent office. Here, John Fitch made the first public announcement of his new invention, the "Steam Boat," and first patent holder

John Fitch made the first public announcement of his new invention, the "Steam Boat," and first patent holder Samuel Hopkins published his pamphlet on the improved production of potash. Here,

Samuel Hopkins published his pamphlet on the improved production of potash. Here,  John Beale Bordley and the

John Beale Bordley and the  Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture published their latest findings on scientific agriculture. Here, too, Tench Coxe co-authored the influential Report on Manufactures (1791) with Alexander Hamilton, and documented

Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture published their latest findings on scientific agriculture. Here, too, Tench Coxe co-authored the influential Report on Manufactures (1791) with Alexander Hamilton, and documented  Pennsylvania's growing economy.

Pennsylvania's growing economy.

It was this concentration of expertise that led President Thomas Jefferson to send Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia in 1803 for the training he and George Rogers Clark would need to lead their great Expedition of Discovery across the uncharted continent. Lewis consulted with botanists Benjamin Smith Barton and

Benjamin Smith Barton and  William Bartram, the author of Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, etc. (1791), a groundbreaking work of American natural history praised on both sides of the Atlantic. To prepare for possible encounters with live Mastodons, Lewis met with paleontologist

William Bartram, the author of Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, etc. (1791), a groundbreaking work of American natural history praised on both sides of the Atlantic. To prepare for possible encounters with live Mastodons, Lewis met with paleontologist  Dr. Caspar Wistar, who in 1811 would publish the first American textbook on anatomy.

Dr. Caspar Wistar, who in 1811 would publish the first American textbook on anatomy.

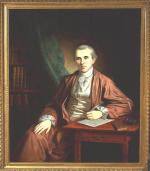

To acquire the medical knowledge and supplies needed for the expedition and to learn about how to study the Native-American tribes he would encounter, Lewis met with doctor Benjamin Rush. A physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence second only to Franklin in the breadth of his interests and impact of his ideas, Rush wrote on subjects ranging from the ratification of the Constitution and proper function of education in the new republic for both

Benjamin Rush. A physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence second only to Franklin in the breadth of his interests and impact of his ideas, Rush wrote on subjects ranging from the ratification of the Constitution and proper function of education in the new republic for both  men and

men and  women to American-Indian medicine, the treatment of the mentally ill, and the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. It was in Philadelphia, too, that

women to American-Indian medicine, the treatment of the mentally ill, and the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793. It was in Philadelphia, too, that  Nicholas Biddle would edit the authoritative account of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Nicholas Biddle would edit the authoritative account of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Pennsylvanians who lived through the world-shaking events of the 1770s and 1780s faced the great challenge of securing independence and forging of a new nation. The United States Constitution, framed in Philadelphia, was not accepted without a struggle. It was Pennsylvanians

In the decades that followed, a task of equal importance was to memorialize the struggles and principles upon which the nation had been founded. More memorials, histories, and other books and magazines came out of Philadelphia, the publishing center of the nation, than any other city. The first major history of the American Revolution, written by

The first best-selling biography, "Parson" Mason Weems's Life of Washington, was first printed in extended form by Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey of Philadelphia, for whom Weems worked as a salesman. In it, Weems included the famous story about the cherry tree and otherwise played fast and loose with the historical truth. Published in Philadelphia in 1796, William Findley's History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania in the Year 1794 provided Americans the first book-length account of the Whiskey Rebellion, a history written from the perspective of the Whiskey Rebels rather than the federal government that had suppressed it.

The orations and essays of women, too, were published to convince females that their role as republican citizens required them to be virtuous educators of the next generation. Some women, however, went beyond what the men had hoped would be their "sphere" and demanded political rights as well.

Philadelphia was the political capitol of the United States until 1800, but well into the nineteenth century it remained the "Athens of America"-the nation's scientific, literary, and artistic center. Here in the 1790s, as the new United States struggled to remain neutral in the war between Revolutionary France and Great Britain and its monarchist allies, the thoughtfulness and eloquence of the Revolutionary generation gave way to political journalists whose sniping partisanship and personal nastiness fueled the fires of America's first political parties: the pro-French Democratic-Republicans, and pro-English Federalists. This first generation of political journalists included native Pennsylvanians and newcomers.

On the Federalist side were John Fenno, who brought his Gazette of the United States down from New York to become the unofficial publication of the ruling party; the prickly tongued "Peter Porcupine," the pen name of English expatriate William Cobbett; and "Oliver Oldschool Jr," the Bostonian Joseph Dennie, charged in 1803 with seditious libel for his scathing attacks on Thomas Jefferson.

Prominent writers for the Democratic-Republicans included Irish-born Federalist-turned-Jeffersonian Mathew Carey, a staunch defender of a strong American navy; New Yorker Philip Freneau, who was also one of the nation's most celebrated poets;

While the city's journals inflamed passions in their full-bore attempts to sway public opinion, its printers were releasing a wealth of other publications. American magazine culture had been centered in Philadelphia since Benjamin Franklin began publication of the General Magazine in the early 1740s. From the 1780s onwards, a new generation of magazines committed to "public instruction and amusement," including The Port Folio, Columbian Magazine, and The American Museum, featured eclectic offerings of material from Europe and the United States for American readers. These included the satires, essays, the songs of Philadelphian Francis Hopkinson and the patriotic poems of Philip Freneau.

In their own attempts to make sense of what was taking place in the new nation, America's first novelists sold their books. The first bestseller was Susanna Rowson's Charlotte Temple (1790 or 1791), in which a damsel in distress suffers both physical and psychological torment. The first American to try to earn his living as a novelist (without much success) was Charles Brockden Brown, Philadelphia publisher of the short-lived Literary Magazine. In his groundbreaking novels illustrating "some important branches of the moral constitution of man"- Wieland (1798), Ormond (1799), Edgar Huntly (1799), and Arthur Mervyn (1799)- Brown created the overwrought concoctions of murder, seduction and romance, disease, and multiple forms of gothic terror, making Philadelphia the birthplace of American Gothic fiction and presenting a very different version of the world from contemporaries' optimistic hopes that a virtuous republic could solve many of humankind's problems.

Brown's brand of Gothic fiction would soon become associated with Philadelphia through the works of Robert Montgomery Bird and George Lippard. They, in turn, would influence writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe on to Stephen King and other current literary masters of horror.

In western Pennsylvania, Hugh Henry Brackenridge, founder of the

Philadelphia was also the center of technological industrial innovations explained in pages of magazines and books published in the city. Following passage of the Patent Act of 1790, the American Philosophical Society served as the nation's first patent office. Here,

It was this concentration of expertise that led President Thomas Jefferson to send Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia in 1803 for the training he and George Rogers Clark would need to lead their great Expedition of Discovery across the uncharted continent. Lewis consulted with botanists

To acquire the medical knowledge and supplies needed for the expedition and to learn about how to study the Native-American tribes he would encounter, Lewis met with doctor