Chapter Two: The Industrial Age

In the second half of the 19th century, Pennsylvania became an industrial powerhouse and center of technological innovations. Blessed with abundant natural resources, the state led the nation in the production of timber, iron, and then of steel, anthracite coal, and a broad array of manufactured products. To move raw materials and finished goods, new private enterprises, often subsidized by state government, constructed an ever-expanding network of roads, canals, and railroads, along which small country hamlets grew into industrial boom towns and whole cities were built from scratch.

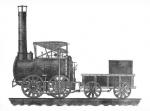

Pennsylvania had led the colonies and then the new nation in the production of iron, and it was in Pennsylvania's iron plantations and mills that the American railroad and steel industries took shape. It was the need to haul anthracite coal that brought the first British locomotive, the Stourbridge Lion, to the United States in 1829. Pennsylvanians played important roles in transforming the small, dangerous and unreliable iron horse of the early 1800s into the great long-distance transportation systems that followed.

Stourbridge Lion, to the United States in 1829. Pennsylvanians played important roles in transforming the small, dangerous and unreliable iron horse of the early 1800s into the great long-distance transportation systems that followed.

In 1844, Richard Osborne, an iron worker in the Philadelphia and Reading Railroads' Pottstown shops, designed the first American iron railroad bridge, constructed across a small creek along the Schuylkill River in Manayunk, to carry coal to Philadelphia. A year later, the Montour Iron Works of Danville rolled the

iron railroad bridge, constructed across a small creek along the Schuylkill River in Manayunk, to carry coal to Philadelphia. A year later, the Montour Iron Works of Danville rolled the  first iron T-rails. Pioneering locomotive designers included

first iron T-rails. Pioneering locomotive designers included  Phineas T. Davis and Charles D. Scott, whose geared

Phineas T. Davis and Charles D. Scott, whose geared  Climax locomotives were used by logging companies around the world. In Saxonburg, Pa., German engineer

Climax locomotives were used by logging companies around the world. In Saxonburg, Pa., German engineer  John Roebling in the 1840s developed the wire rope that would revolutionize the design of American bridges.

John Roebling in the 1840s developed the wire rope that would revolutionize the design of American bridges.

It was at the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown that "Crazy" John Kelly in 1857 first tried to make steel by blowing cold air through red-hot molten iron. There, too, engineer

John Kelly in 1857 first tried to make steel by blowing cold air through red-hot molten iron. There, too, engineer  John Fritz designed the first "three-high" mill for the production of railroad rails. In 1866, Steelton became the first mill in the United States dedicated exclusively to making steel. The next year, the nation's

John Fritz designed the first "three-high" mill for the production of railroad rails. In 1866, Steelton became the first mill in the United States dedicated exclusively to making steel. The next year, the nation's  first steel rails were rolled at Cambria Iron Works.

first steel rails were rolled at Cambria Iron Works.

Steel would transform Pittsburgh into an economic juggernaut with an extraordinary concentration of resources and vast investment capital. This, in turn, attracted others eager to transform their expertise and discoveries into successful businesses and industries. It was Pittsburgh newcomer

Pittsburgh into an economic juggernaut with an extraordinary concentration of resources and vast investment capital. This, in turn, attracted others eager to transform their expertise and discoveries into successful businesses and industries. It was Pittsburgh newcomer  George W.G. Ferris, for example, whose giant Ferris wheel-built with steel fabricated in Pittsburgh and Bethlehem-thrilled visitors at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

George W.G. Ferris, for example, whose giant Ferris wheel-built with steel fabricated in Pittsburgh and Bethlehem-thrilled visitors at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

It was investment capital that drew metallurgist Charles Martin Hall to Pittsburgh in 1886, where he and his partners transformed the electrolytic process he had invented to produce commercially affordable aluminum into what became the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA). Funded by the Mellon National Bank,

Charles Martin Hall to Pittsburgh in 1886, where he and his partners transformed the electrolytic process he had invented to produce commercially affordable aluminum into what became the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA). Funded by the Mellon National Bank,  Edward Acheson in 1894 started the Carborundum Company in Monongahela to produce carborundum, an industrial abrasive whose patent the U.S. Patent Office would later consider one of the most important of America's industrial age.

Edward Acheson in 1894 started the Carborundum Company in Monongahela to produce carborundum, an industrial abrasive whose patent the U.S. Patent Office would later consider one of the most important of America's industrial age.

In Pittsburgh George Westinghouse manufactured the airbrakes that revolutionized the American railroad industry and created the

George Westinghouse manufactured the airbrakes that revolutionized the American railroad industry and created the  Westinghouse Electrical Company, which, by 1900, split control of America's emerging electrical industry with General Electric. Acheson, Hall and Westinghouse all represented the growing impact of science upon the American economy. In the late 1800s, science-based industries, including steel and aluminum, petroleum and electricity, were driving America's economic growth and technological advances more than ever before were based on breakthroughs on chemistry and physics.

Westinghouse Electrical Company, which, by 1900, split control of America's emerging electrical industry with General Electric. Acheson, Hall and Westinghouse all represented the growing impact of science upon the American economy. In the late 1800s, science-based industries, including steel and aluminum, petroleum and electricity, were driving America's economic growth and technological advances more than ever before were based on breakthroughs on chemistry and physics.

To train the men and women needed by Pennsylvania's industries, Commonwealth schools revamped their curricula. In 1859, agricultural chemist Evan Pugh became first president of the

Evan Pugh became first president of the  Agricultural College of Pennsylvania (today's Penn State University) and began to introduce the scientific curricula that would make Penn State a major center of agricultural science and engineering. To stimulate progress and innovation, Pennsylvania's captains of industry funded colleges and institutes to train the engineers and agronomists, foresters, and scientists needed by the state and the nation.

Agricultural College of Pennsylvania (today's Penn State University) and began to introduce the scientific curricula that would make Penn State a major center of agricultural science and engineering. To stimulate progress and innovation, Pennsylvania's captains of industry funded colleges and institutes to train the engineers and agronomists, foresters, and scientists needed by the state and the nation.

Founded in 1865 with an endowment from canal and railroad magnate Asa Packer, Lehigh University became the first college in the Commonwealth to offer a science-based program of study combined with a classical education. There,

Lehigh University became the first college in the Commonwealth to offer a science-based program of study combined with a classical education. There,  John F. Fritz in 1909 funded and designed a state-of-the-art engineering laboratory for testing steel, cement, and concrete. Established colleges, including the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pennsylvania, received large infusions of money to expand their curricula in science and engineering, and were joined by new technical schools, including the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry (1891), the Carnegie Technical Institute (1900), and the Mont Alto Forest Academy (1903). By the late 1800s, most scientists and inventors had received a college education and worked in research laboratories or in large, innovative machine shops.

John F. Fritz in 1909 funded and designed a state-of-the-art engineering laboratory for testing steel, cement, and concrete. Established colleges, including the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pennsylvania, received large infusions of money to expand their curricula in science and engineering, and were joined by new technical schools, including the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry (1891), the Carnegie Technical Institute (1900), and the Mont Alto Forest Academy (1903). By the late 1800s, most scientists and inventors had received a college education and worked in research laboratories or in large, innovative machine shops.

Pennsylvania's shops and mills were also centers of innovation, and trained a vast pool of young men in an extraordinary range of skills. Although he had little formal education, Pittsburgh machinist John Brashear, in the 1870s crafted telescope lenses of unprecedented quality in an coal shed attached to the back of his house, then went on to become a world-renowned astronomer and maker of exquisitely precise telescopes. Brashear found a sponsor in Pittsburgh businessman William Thaw, who also underwrote the construction of the

John Brashear, in the 1870s crafted telescope lenses of unprecedented quality in an coal shed attached to the back of his house, then went on to become a world-renowned astronomer and maker of exquisitely precise telescopes. Brashear found a sponsor in Pittsburgh businessman William Thaw, who also underwrote the construction of the  Allegheny Observatory. On the hills of Chester County, farm implement manufacturer Samuel Leads Allen in the 1880s invented the

Allegheny Observatory. On the hills of Chester County, farm implement manufacturer Samuel Leads Allen in the 1880s invented the  Flexible Flyer snow sled.

Flexible Flyer snow sled.

Commercial success depended upon men with the finances and entrepreneurial skills to turn inventions into profits. In the late 1880s, Luzerne County machinist Sephaniah Reese used old fire hose and Civil War bayonet scabbards to build one of the nation's first horseless carriages. His failure to turn his hobby into a business enterprise, however, has relegated him to a historical footnote. In 1868, printer

Sephaniah Reese used old fire hose and Civil War bayonet scabbards to build one of the nation's first horseless carriages. His failure to turn his hobby into a business enterprise, however, has relegated him to a historical footnote. In 1868, printer  Christopher Sholes filed the first patent for a "Type-Writer," an invention that came to market only through the dogged determination of investor James Densmore, who, with his brother Amos, had in 1865 invented the

Christopher Sholes filed the first patent for a "Type-Writer," an invention that came to market only through the dogged determination of investor James Densmore, who, with his brother Amos, had in 1865 invented the first oil tank car to transport oil out of Pennsylvania's booming oil fields.

first oil tank car to transport oil out of Pennsylvania's booming oil fields.

Hobbyists and gentlemen amateurs also continued to tinker, experiment and patent their own, (and, at times, other's) inventions. After brewing phosphorous on his office stove, Philadelphia patent lawyer Joshua Pusey in 1892 patented the most successful of his nearly forty patented inventions: the Flexible Match. The history of great inventions is rarely simple, and the more valuable the breakthrough, the greater the scramble for its credit and rewards. In 1880 Cumberland County's

Joshua Pusey in 1892 patented the most successful of his nearly forty patented inventions: the Flexible Match. The history of great inventions is rarely simple, and the more valuable the breakthrough, the greater the scramble for its credit and rewards. In 1880 Cumberland County's  Daniel Drawbaugh, "the Wizard of Eberly's Mills," filed a bogus patent for the invention of the telephone that unleashed litigation with the Bell Telephone Company that would drag on until 1911.

Daniel Drawbaugh, "the Wizard of Eberly's Mills," filed a bogus patent for the invention of the telephone that unleashed litigation with the Bell Telephone Company that would drag on until 1911.

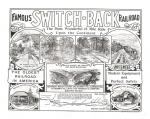

In the 19th century, the impact of science and invention spread its way throughout American society and culture. New technologies created a growing range of industrial pollutants, transformed entertainment and leisure, and shaped new attitudes about human life and machines. After the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company's switchback railroad became obsolete for hauling coal, it became a thrill-packed gravity ride for tourists, and inspired Philadelphian Edward Joy Morris to design the safety-wheel system for the modern roller coaster. Morris would build more than 250 Figure Eight roller coasters across the United States, including

switchback railroad became obsolete for hauling coal, it became a thrill-packed gravity ride for tourists, and inspired Philadelphian Edward Joy Morris to design the safety-wheel system for the modern roller coaster. Morris would build more than 250 Figure Eight roller coasters across the United States, including  Leap the Dips, which he installed at Altoona's Lakemont Park in 1902. In 1897, Philadelphia optician

Leap the Dips, which he installed at Altoona's Lakemont Park in 1902. In 1897, Philadelphia optician  Siegmund Lubin built, patented and marketed his first motion picture projector, the Cineograph, on his way to becoming one of the world's largest manufacturers of "life movies."

Siegmund Lubin built, patented and marketed his first motion picture projector, the Cineograph, on his way to becoming one of the world's largest manufacturers of "life movies."

Intent on discovering the "laws" that governed how much heavy work a man could do, Philadelphia engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor in the early 1900s conducted the "scientific" time and motion studies of a most uncommon laborer at the Bethlehem Steel Company's Midvale mill in Philadelphia that would become the basis of modern "scientific management" of the workplace, and of the work speed-up programs that would plague industrial workers in the decades that followed.

of a most uncommon laborer at the Bethlehem Steel Company's Midvale mill in Philadelphia that would become the basis of modern "scientific management" of the workplace, and of the work speed-up programs that would plague industrial workers in the decades that followed.

Pennsylvanians and their resources played key roles in the development of electrical industry. In 1883, Edison set up his first Direct Current, three-wire electric lighting system at Sunbury, in Northumberland County, because of its proximity to anthracite coal, an abundant and inexpensive fuel source. Three years later, Scranton built the

electric lighting system at Sunbury, in Northumberland County, because of its proximity to anthracite coal, an abundant and inexpensive fuel source. Three years later, Scranton built the  first American street car system entirely powered by electricity. In 1893, Pittsburgh's George Westinghouse, bested Edison by powering the Chicago's World Columbian Exposition with electricity, and demonstrating the safety and reliable of Alternating Current (AC). Less than a decade later, Westinghouse would establish its own research laboratories.

first American street car system entirely powered by electricity. In 1893, Pittsburgh's George Westinghouse, bested Edison by powering the Chicago's World Columbian Exposition with electricity, and demonstrating the safety and reliable of Alternating Current (AC). Less than a decade later, Westinghouse would establish its own research laboratories.

In the 1900s, the increasing complexity of science and the expense of research, development, and production would fuel the further the institutionalization of scientific and invention.

Pennsylvania had led the colonies and then the new nation in the production of iron, and it was in Pennsylvania's iron plantations and mills that the American railroad and steel industries took shape. It was the need to haul anthracite coal that brought the first British locomotive, the

In 1844, Richard Osborne, an iron worker in the Philadelphia and Reading Railroads' Pottstown shops, designed the first American

It was at the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown that "Crazy"

Steel would transform

It was investment capital that drew metallurgist

In Pittsburgh

To train the men and women needed by Pennsylvania's industries, Commonwealth schools revamped their curricula. In 1859, agricultural chemist

Founded in 1865 with an endowment from canal and railroad magnate Asa Packer,

Pennsylvania's shops and mills were also centers of innovation, and trained a vast pool of young men in an extraordinary range of skills. Although he had little formal education, Pittsburgh machinist

Commercial success depended upon men with the finances and entrepreneurial skills to turn inventions into profits. In the late 1880s, Luzerne County machinist

Hobbyists and gentlemen amateurs also continued to tinker, experiment and patent their own, (and, at times, other's) inventions. After brewing phosphorous on his office stove, Philadelphia patent lawyer

In the 19th century, the impact of science and invention spread its way throughout American society and culture. New technologies created a growing range of industrial pollutants, transformed entertainment and leisure, and shaped new attitudes about human life and machines. After the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company's

Intent on discovering the "laws" that governed how much heavy work a man could do, Philadelphia engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor in the early 1900s conducted the "scientific" time and motion studies

Pennsylvanians and their resources played key roles in the development of electrical industry. In 1883, Edison set up his first Direct Current, three-wire

In the 1900s, the increasing complexity of science and the expense of research, development, and production would fuel the further the institutionalization of scientific and invention.