Chapter One: The Mechanical Age

For thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, Indians living in what would become Pennsylvania developed technologies to improve their lives and to help them better exploit the natural resources they relied upon for sustenance. They invented effective systems of snares and weapons to hunt and catch animals. Learning that fish could be caught by putting mashed black walnuts in open water, the Lenape, for example, used the naturally occurring chemicals from the crushed mixture of hulls and nuts to stun fish, which they gathered as they floated to the surface.

Throughout the Americas, healers treated their peoples' illnesses with medicines made from a tremendous variety of plants and herbs. Their knowledge of medical botany was no defense, however, against the host of new very deadly diseases brought by European traders and settlers from the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland in the 1600s. Virgin soil epidemics -those that spread among people with no previous exposure or resistance - of influenza, measles, smallpox, and other diseases decimated Indian populations.

In colonial Pennsylvania, and early America as a whole, the scarcity of labor drove farmers and craftsmen to fashion labor saving devices and other inventions to ease their work and improve their lives. Eighteenth-century Pennsylvanians had many skills, for they needed to know how to produce and preserve their food; make cloth, clothing, furniture, and tools; build homes and mills; treat illnesses; and design, construct, and repair an ever-growing variety of machines. In the colony's backcountry, anonymous craftsmen created the Conestoga wagon to better haul farm produce over great distances, the Durham boat for river transportation, and the

Conestoga wagon to better haul farm produce over great distances, the Durham boat for river transportation, and the  Pennsylvania rifle, the highly accurate, indispensable firearm of the American frontier. The drive to tinker, invent, and improve was handed down from one generation to the next, as can be seen in the biographies of

Pennsylvania rifle, the highly accurate, indispensable firearm of the American frontier. The drive to tinker, invent, and improve was handed down from one generation to the next, as can be seen in the biographies of  Samuel Sellers of Delaware County and his descendents.

Samuel Sellers of Delaware County and his descendents.

The open political and social climate of colonial Pennsylvania encouraged and nurtured creativity. In 1723, a seventeen-year-old apprentice printer from Boston named Benjamin Franklin landed in Philadelphia, then the largest and most cosmopolitan city in British North America. Here, Franklin found a community eager to embrace his quest for "improvement." Franklin would become one of the eighteenth century's most important and celebrated inventor/scientists, a man honored and revered on both sides of the Atlantic.

Benjamin Franklin landed in Philadelphia, then the largest and most cosmopolitan city in British North America. Here, Franklin found a community eager to embrace his quest for "improvement." Franklin would become one of the eighteenth century's most important and celebrated inventor/scientists, a man honored and revered on both sides of the Atlantic.

Applying his curious mind to the world around him, Franklin invented an improved stove, bifocals, and lightning rod. He charted the Gulf Stream and became the world's leading expert on electricity. He helped found and finance institutions for the advancement of science and gathered around him an extraordinary group of amateur scientists who helped make Philadelphia the scientific center of Britain's North American colonies. One of Franklin's close friends was clockmaker David Rittenhouse,who became America's first great astronomer, and who in 1743 helped Franklin found the American Philosophical Society (APS), organized to promote useful knowledge and science.

David Rittenhouse,who became America's first great astronomer, and who in 1743 helped Franklin found the American Philosophical Society (APS), organized to promote useful knowledge and science.

After the trials and tumult of the American Revolution, Philadelphia, now the nation's capital, flourished as the center of American cultural, political, and scientific life. As competition with the products of British science and industry gave added urgency to American scientific and technological efforts, APS emerged as the most important learned society in North America, serving as the nation's first patent office and home to the nation's first natural history museum. Embracing the Enlightenment ideal of improving society through the application of science, Philadelphians founded the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture (1785), the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts (1787), The Academy of Natural Sciences (1812), and the Franklin Institute (1824). Pennsylvania's openness to new ideas also continued to attract Europeans, including renowned British scientist and religious nonconformist

Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture (1785), the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts (1787), The Academy of Natural Sciences (1812), and the Franklin Institute (1824). Pennsylvania's openness to new ideas also continued to attract Europeans, including renowned British scientist and religious nonconformist  Joseph Priestley, who emigrated to Northumberland County in 1794.

Joseph Priestley, who emigrated to Northumberland County in 1794.

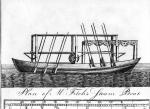

In August 1787, while Franklin and the other "Founding Fathers" were drafting a new constitution to create "a more perfect union" for the new nation, John Fitch,a one-time brass maker, clock repairer, gunsmith, mapmaker, and silversmith, launched the world's first steamboat, on the Delaware River. Fitch never received the credit or financial rewards he deserved for an invention that would transform the nation. In 1798, broke and dispirited, he would take his own life in Bardstown, Kentucky.

John Fitch,a one-time brass maker, clock repairer, gunsmith, mapmaker, and silversmith, launched the world's first steamboat, on the Delaware River. Fitch never received the credit or financial rewards he deserved for an invention that would transform the nation. In 1798, broke and dispirited, he would take his own life in Bardstown, Kentucky.

In the summer of 1787, however, delegates to the Constitutional Convention included a provision in the new Constitution to promote science and invention by giving the United States Congress the power to issue patents. In 1790, the nation's new Patent Board issued the first American patent to Samuel Hopkins or his new method of making potash, an important, multi-purpose industrial chemical. And in 1807, Pennsylvanian

Samuel Hopkins or his new method of making potash, an important, multi-purpose industrial chemical. And in 1807, Pennsylvanian  Robert Fulton, who may well have witnessed Fitch's first steamboat demonstration twenty years before, powered his own steamboat, the Clermont, up the Hudson River and into history.

Robert Fulton, who may well have witnessed Fitch's first steamboat demonstration twenty years before, powered his own steamboat, the Clermont, up the Hudson River and into history.

In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia, proclaimed by some to be "the Athens of America," for the scientific and medical training he needed to lead his great expedition across North America. Here he consulted with

Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia, proclaimed by some to be "the Athens of America," for the scientific and medical training he needed to lead his great expedition across North America. Here he consulted with  Benjamin Rush about medicine and anthropology,

Benjamin Rush about medicine and anthropology, Benjamin Smith Barton about botany,

Benjamin Smith Barton about botany,  Caspar Wistar about paleontology, and mathematician

Caspar Wistar about paleontology, and mathematician  Robert Patterson about map-making. And it was here that Lewis purchased the scientific instruments and other vital supplies that he would bring with his Corps of Discovery. In the decades that followed, scientists associated with the American Philosophical Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences would themselves take part in many of the other great explorations of discovery, on land and at sea, that were to follow.

Robert Patterson about map-making. And it was here that Lewis purchased the scientific instruments and other vital supplies that he would bring with his Corps of Discovery. In the decades that followed, scientists associated with the American Philosophical Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences would themselves take part in many of the other great explorations of discovery, on land and at sea, that were to follow.

In the decades that followed, booming economic growth, new transportation systems, soaring populations, and new inventions transformed the nation. Village-based economies, built around farming communities that contained most of the skills to make what they needed, gave way to a market-based economy in which more and more people worked for wages used to purchase manufactured goods. At the same time, scientific breakthroughs and new technologies were challenging how Americans understood the world and forcing them to question the sacred truths of the Bible and folk knowledge of their ancestors.

A decade before P.T. Barnum convinced many Americans that one could see the "Man in the Moon" through a telescope, German showman John Maelzel baffled Philadelphians with his "Turk," a machine - or so he said - that could play chess better than most people. In 1839, chemist

John Maelzel baffled Philadelphians with his "Turk," a machine - or so he said - that could play chess better than most people. In 1839, chemist  Robert Cornelius took the first American photograph when he captured a ghostly image of Philadelphia's Central High School on a silver plate.

Robert Cornelius took the first American photograph when he captured a ghostly image of Philadelphia's Central High School on a silver plate.

Gentleman scientists, including botanist William Darlington of West Chester and the multi-talented

William Darlington of West Chester and the multi-talented  Samuel Haldeman from Lancaster County, continued to document and classify the world's flora and fauna. And a new generation of college and institution-based researchers were advancing the professionalization of American science, including Philadelphia paleontologist

Samuel Haldeman from Lancaster County, continued to document and classify the world's flora and fauna. And a new generation of college and institution-based researchers were advancing the professionalization of American science, including Philadelphia paleontologist  Edward Drinker Cope, who amazed Americans with his reconstructions of the gigantic "thunder lizards" that had roamed the North American continent millions of years before the evolution of humans-and engaged in fierce battles with his academic adversaries.

Edward Drinker Cope, who amazed Americans with his reconstructions of the gigantic "thunder lizards" that had roamed the North American continent millions of years before the evolution of humans-and engaged in fierce battles with his academic adversaries.

Blessed with abundant raw materials, skilled workers, innovative entrepreneurs, and intrepid inventors, Pennsylvania in the decades before the Civil War was emerging as an industrial powerhouse. Pennsylvania's grain, anthracite coal, iron, and textile industries were all the source of significant technological innovations. Fueled by northeastern Pennsylvania's anthracite coal, Philadelphia became the nation's first industrial city. There, in 1791, William Sprague opened the nation's first woven carpet mill. In Wetherill (now part of Bethlehem) in the 1850s, chemist Samuel Wetherilldeveloped a process for the extraction of zinc oxide that revolutionized the American paint industry. In the decades that followed, industrialization unleashed a wave of technological innovation and scientific breakthroughs that would transform the nation.

Samuel Wetherilldeveloped a process for the extraction of zinc oxide that revolutionized the American paint industry. In the decades that followed, industrialization unleashed a wave of technological innovation and scientific breakthroughs that would transform the nation.

Throughout the Americas, healers treated their peoples' illnesses with medicines made from a tremendous variety of plants and herbs. Their knowledge of medical botany was no defense, however, against the host of new very deadly diseases brought by European traders and settlers from the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland in the 1600s. Virgin soil epidemics -those that spread among people with no previous exposure or resistance - of influenza, measles, smallpox, and other diseases decimated Indian populations.

In colonial Pennsylvania, and early America as a whole, the scarcity of labor drove farmers and craftsmen to fashion labor saving devices and other inventions to ease their work and improve their lives. Eighteenth-century Pennsylvanians had many skills, for they needed to know how to produce and preserve their food; make cloth, clothing, furniture, and tools; build homes and mills; treat illnesses; and design, construct, and repair an ever-growing variety of machines. In the colony's backcountry, anonymous craftsmen created the

The open political and social climate of colonial Pennsylvania encouraged and nurtured creativity. In 1723, a seventeen-year-old apprentice printer from Boston named

Applying his curious mind to the world around him, Franklin invented an improved stove, bifocals, and lightning rod. He charted the Gulf Stream and became the world's leading expert on electricity. He helped found and finance institutions for the advancement of science and gathered around him an extraordinary group of amateur scientists who helped make Philadelphia the scientific center of Britain's North American colonies. One of Franklin's close friends was clockmaker

After the trials and tumult of the American Revolution, Philadelphia, now the nation's capital, flourished as the center of American cultural, political, and scientific life. As competition with the products of British science and industry gave added urgency to American scientific and technological efforts, APS emerged as the most important learned society in North America, serving as the nation's first patent office and home to the nation's first natural history museum. Embracing the Enlightenment ideal of improving society through the application of science, Philadelphians founded the

In August 1787, while Franklin and the other "Founding Fathers" were drafting a new constitution to create "a more perfect union" for the new nation,

In the summer of 1787, however, delegates to the Constitutional Convention included a provision in the new Constitution to promote science and invention by giving the United States Congress the power to issue patents. In 1790, the nation's new Patent Board issued the first American patent to

In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sent

In the decades that followed, booming economic growth, new transportation systems, soaring populations, and new inventions transformed the nation. Village-based economies, built around farming communities that contained most of the skills to make what they needed, gave way to a market-based economy in which more and more people worked for wages used to purchase manufactured goods. At the same time, scientific breakthroughs and new technologies were challenging how Americans understood the world and forcing them to question the sacred truths of the Bible and folk knowledge of their ancestors.

A decade before P.T. Barnum convinced many Americans that one could see the "Man in the Moon" through a telescope, German showman

Gentleman scientists, including botanist

Blessed with abundant raw materials, skilled workers, innovative entrepreneurs, and intrepid inventors, Pennsylvania in the decades before the Civil War was emerging as an industrial powerhouse. Pennsylvania's grain, anthracite coal, iron, and textile industries were all the source of significant technological innovations. Fueled by northeastern Pennsylvania's anthracite coal, Philadelphia became the nation's first industrial city. There, in 1791, William Sprague opened the nation's first woven carpet mill. In Wetherill (now part of Bethlehem) in the 1850s, chemist