Chapter 3: The New Deal in Pennsylvania: Public Works and Organized Labor

For more than a decade, the Great Depression devastated Pennsylvania and the nation. It also forced Americans to grapple anew with fundamental questions about the role of government. In desperate need of change, the nation in 1932 elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt president.

Once in office, FDR and Congress created a package of programs that provided relief for the jobless through public works projects and pro-labor legislation that empowered those with jobs. For the first time in American history, the federal government assumed responsibility for the basic welfare of impoverished Americans. Many hailed Roosevelt's New Deal as a monumental victory for the common man and woman. Others feared it represented an insidious threat to the Republic.

In 1930, Pennsylvania had a mixed economy based on diversified industries and agriculture, and a blend of urban and rural populations. Employing nearly a million factory and mill workers, the Commonwealth was an economic powerhouse, out-produced in manufacturing only by New York. The Great Depression hit Pennsylvania hard.

Between 1927 and 1933, more than 5,000 manufacturing firms closed, and factory jobs plummeted by 270,000. Cities, where the most jobs were lost, suffered terribly. Joblessness, poverty, and destitution also found their way into Pennsylvania's rural areas; into farms in mountain hollows, patch towns in the coal regions, and logging villages in upstate forests. In rural Fayette County, for example, 37 percent of the work force was jobless in 1937.

In Pennsylvania, as in the rest of the nation, traditional forms of poor relief through private charities, county poor boards, and urban political parties quickly collapsed under the weight of the unprecedented mass misery wrought by the Depression. Efforts on the part of the financially drained state and local governments also failed to alleviate the suffering. In August 1931, Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot proclaimed that "the only power strong enough, and able to act in time, to meet the new problem of the coming winter is the Government of the United States." Pinchot inaugurated an ambitious state work relief program, hiring thousands of unemployed men to construct roads that would

Gifford Pinchot proclaimed that "the only power strong enough, and able to act in time, to meet the new problem of the coming winter is the Government of the United States." Pinchot inaugurated an ambitious state work relief program, hiring thousands of unemployed men to construct roads that would  "connect farm to market." Substantial action by the federal government did not come, however, until after FDR took office in January, 1933.

"connect farm to market." Substantial action by the federal government did not come, however, until after FDR took office in January, 1933.

To revive the nation's economy, Roosevelt supported "priming the pump," by generating jobs and consumer spending through federally financed public works projects. Created by the National Industrial Recovery Act on June 16, 1933, the Public Works Administration (PWA) budgeted several billion dollars for the construction of public works.

Overseeing the PWA and other New Deal relief programs was Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, who had been born in Altoona, PA. Between July 1933 and March 1939, the PWA spent over $6 billion on more than 34,000 construction projects, including the

Harold L. Ickes, who had been born in Altoona, PA. Between July 1933 and March 1939, the PWA spent over $6 billion on more than 34,000 construction projects, including the  Pennsylvania Turnpike, the nation's first limited access superhighway. To put unemployed young men to work, and at the same time conserve timber, soil, and water resources, Congress also established the

Pennsylvania Turnpike, the nation's first limited access superhighway. To put unemployed young men to work, and at the same time conserve timber, soil, and water resources, Congress also established the  Civilian Conservation Corps, which in Pennsylvania alone employed more than 200,000 young men.

Civilian Conservation Corps, which in Pennsylvania alone employed more than 200,000 young men.

Dominated by conservative Republicans who opposed federal intervention in state affairs - and feared that it would invigorate their Democratic opponents- Pennsylvania's state legislature refused federal funding. Only after the 1936 election, in which Democrats gained control of the state House and George H. Earle became the first Democratic governor since the 1890s, did New Deal moneys flow more freely during what became known as Pennsylvania's "Little New Deal."

George H. Earle became the first Democratic governor since the 1890s, did New Deal moneys flow more freely during what became known as Pennsylvania's "Little New Deal."

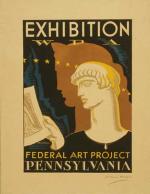

In the years that followed, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed Pennsylvanians to construct bridges, schools, courthouses, hydroelectric dams, parks, and roads. In addition, the WPA's Federal Art, Theater, and Writer's Projects funded cultural programs that employed teachers, writers, artists, and musicians. The works of local WPA artists, depicting regional scenes of farmers, miners, and factory workers, still grace the walls of courthouses, schools, post offices, and other public buildings throughout the state.

hydroelectric dams, parks, and roads. In addition, the WPA's Federal Art, Theater, and Writer's Projects funded cultural programs that employed teachers, writers, artists, and musicians. The works of local WPA artists, depicting regional scenes of farmers, miners, and factory workers, still grace the walls of courthouses, schools, post offices, and other public buildings throughout the state.

In the wake of the great Flood of 1936, which caused more damage in Pennsylvania than any other state in the Northeast, Congress passed The Flood Control Act of 1936. This act subsidized construction of a system of dams, levees, and channels along the state's numerous flood-prone waterways. Most notable of these was the

state in the Northeast, Congress passed The Flood Control Act of 1936. This act subsidized construction of a system of dams, levees, and channels along the state's numerous flood-prone waterways. Most notable of these was the  Johnstown Local Flood Protection Project, which became the second largest flood control project of its type in the nation.

Johnstown Local Flood Protection Project, which became the second largest flood control project of its type in the nation.

New Deal programs also reached out to rural Pennsylvanians. In 1936, 75 percent of the Commonwealth's farm families still lived without electricity. Under the guidance of John M. Carmody, an industrial relations expert from Towanda, PA, the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) provided low-cost loans to consumer-owned electric cooperatives that would serve neglected rural areas. Between 1936 and 1941, the REA funded the formation of fourteen cooperatives in the state, including the

Rural Electrification Administration (REA) provided low-cost loans to consumer-owned electric cooperatives that would serve neglected rural areas. Between 1936 and 1941, the REA funded the formation of fourteen cooperatives in the state, including the  Northwestern Rural Electric Cooperative, which in May 1937 became the Commonwealth's first cooperative to provide the "miracle" of electricity, to 92 farm families. Pennsylvania power companies vehemently opposed these publicly funded cooperatives, building "spite lines" until backed down by Adams County farmers in the "

Northwestern Rural Electric Cooperative, which in May 1937 became the Commonwealth's first cooperative to provide the "miracle" of electricity, to 92 farm families. Pennsylvania power companies vehemently opposed these publicly funded cooperatives, building "spite lines" until backed down by Adams County farmers in the " Battle of the Post Holes," in January, 1941.

Battle of the Post Holes," in January, 1941.

Although Pennsylvania escaped the prolonged drought that turned the American West into the wind-swept Dust Bowl, millions of wooded acres in Pennsylvania faced dire peril. Clearcut by loggers and the then left exposed to the elements, irreplaceable top soil was being lost through erosion. In 1939, the U. S. Soil Conservation Service (SCS) provided technical assistance to six Bucks County farmers that enabled them develop a cooperative plan to protect a 700-acre watershed located on their lands. In the years that followed, their Honey Hollow Watershed would serve as a prototype for thousands of watershed areas established throughout the nation.

Honey Hollow Watershed would serve as a prototype for thousands of watershed areas established throughout the nation.

The New Deal also began to tackle the national crisis in housing. In Philadelphia, the PWA built public housing projects. In western Pennsylvania's rural Westmoreland County, Congress funded the construction of Norvelt, the fourth of nearly 100 cooperative "subsistence homesteads" for unemployed industrial workers that sprouted up across the nation. To help jobless bituminous coal miners and their families in hard hit Fayette County, the American Friends Service Committee constructed

Norvelt, the fourth of nearly 100 cooperative "subsistence homesteads" for unemployed industrial workers that sprouted up across the nation. To help jobless bituminous coal miners and their families in hard hit Fayette County, the American Friends Service Committee constructed  Penn-Craft, one of the few planned communities founded by a private, "faith-based" charitable organization.

Penn-Craft, one of the few planned communities founded by a private, "faith-based" charitable organization.

Decades of laws and court rulings had left millions of American workers at the mercy of their employers. Under provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, promoted by Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, the federal government for the first time in American history guaranteed the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively. The provisions of these two acts were reinforced by Pennsylvania's "Little Wagner Act" of 1937, which created a state Labor Relations Board.

Frances Perkins, and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, the federal government for the first time in American history guaranteed the rights of workers to organize and bargain collectively. The provisions of these two acts were reinforced by Pennsylvania's "Little Wagner Act" of 1937, which created a state Labor Relations Board.

The New Deal's pro-labor legislation fueled a national labor movement in which Pennsylvanians played a leading role. When the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company refused to abide by a National Labor Relations Board's ruling, the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which in a precedent-setting decision, NLRB vs. Jones and Laughlin, upheld workers' right to organize and bargain collectively.

NLRB vs. Jones and Laughlin, upheld workers' right to organize and bargain collectively.

Mobilized by wage cuts and devastating unemployment, workers across the Commonwealth joined unions, engaged in public protests and strikes, marched on Harrisburg, elected pro-labor candidates to public offices, and struggled for a living wage and worker rights. Beginning in 1935, the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) organized unskilled and semi-skilled industrial workers not represented by the trade union-oriented American Federation of Labor. Led by National Director

Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) organized unskilled and semi-skilled industrial workers not represented by the trade union-oriented American Federation of Labor. Led by National Director  John Brophy, a United Mine Workers organizer from western Pennsylvania, the CIO found fertile recruiting ground in Pennsylvania, successfully enrolling large numbers of textile workers, miners, and steelworkers.

John Brophy, a United Mine Workers organizer from western Pennsylvania, the CIO found fertile recruiting ground in Pennsylvania, successfully enrolling large numbers of textile workers, miners, and steelworkers.

Steel was one of the last major industries to hold out against unionization. Empowered by the Wagner Act, the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) on June 17, 1936, launched a drive to organize labor from its new headquarters in Pittsburgh. By the end of the year, SWOC had enrolled 125,000 members. In 1937, strikes broke out in Reading, Johnstown, and among the

Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) on June 17, 1936, launched a drive to organize labor from its new headquarters in Pittsburgh. By the end of the year, SWOC had enrolled 125,000 members. In 1937, strikes broke out in Reading, Johnstown, and among the  chocolate workers in Hershey.

chocolate workers in Hershey.

That May, U. S. Steel finally recognized SWOC as the bargaining agent for its workers. Not all steel companies, however, followed its example. Convinced that New Deal programs and the gains of labor were jeopardizing the nation's economic future, Pennsylvania conservatives mobilized voters, regaining control of state government in the election of 1938, and worked to turn back the rising tide of change. Abroad, fascism and world war represented new challenges that would soon engulf the state and the nation.

Once in office, FDR and Congress created a package of programs that provided relief for the jobless through public works projects and pro-labor legislation that empowered those with jobs. For the first time in American history, the federal government assumed responsibility for the basic welfare of impoverished Americans. Many hailed Roosevelt's New Deal as a monumental victory for the common man and woman. Others feared it represented an insidious threat to the Republic.

In 1930, Pennsylvania had a mixed economy based on diversified industries and agriculture, and a blend of urban and rural populations. Employing nearly a million factory and mill workers, the Commonwealth was an economic powerhouse, out-produced in manufacturing only by New York. The Great Depression hit Pennsylvania hard.

Between 1927 and 1933, more than 5,000 manufacturing firms closed, and factory jobs plummeted by 270,000. Cities, where the most jobs were lost, suffered terribly. Joblessness, poverty, and destitution also found their way into Pennsylvania's rural areas; into farms in mountain hollows, patch towns in the coal regions, and logging villages in upstate forests. In rural Fayette County, for example, 37 percent of the work force was jobless in 1937.

In Pennsylvania, as in the rest of the nation, traditional forms of poor relief through private charities, county poor boards, and urban political parties quickly collapsed under the weight of the unprecedented mass misery wrought by the Depression. Efforts on the part of the financially drained state and local governments also failed to alleviate the suffering. In August 1931, Pennsylvania Governor

To revive the nation's economy, Roosevelt supported "priming the pump," by generating jobs and consumer spending through federally financed public works projects. Created by the National Industrial Recovery Act on June 16, 1933, the Public Works Administration (PWA) budgeted several billion dollars for the construction of public works.

Overseeing the PWA and other New Deal relief programs was Secretary of the Interior

Dominated by conservative Republicans who opposed federal intervention in state affairs - and feared that it would invigorate their Democratic opponents- Pennsylvania's state legislature refused federal funding. Only after the 1936 election, in which Democrats gained control of the state House and

In the years that followed, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed Pennsylvanians to construct bridges, schools, courthouses,

In the wake of the great Flood of 1936, which caused more damage in Pennsylvania than any other

New Deal programs also reached out to rural Pennsylvanians. In 1936, 75 percent of the Commonwealth's farm families still lived without electricity. Under the guidance of John M. Carmody, an industrial relations expert from Towanda, PA, the

Although Pennsylvania escaped the prolonged drought that turned the American West into the wind-swept Dust Bowl, millions of wooded acres in Pennsylvania faced dire peril. Clearcut by loggers and the then left exposed to the elements, irreplaceable top soil was being lost through erosion. In 1939, the U. S. Soil Conservation Service (SCS) provided technical assistance to six Bucks County farmers that enabled them develop a cooperative plan to protect a 700-acre watershed located on their lands. In the years that followed, their

The New Deal also began to tackle the national crisis in housing. In Philadelphia, the PWA built public housing projects. In western Pennsylvania's rural Westmoreland County, Congress funded the construction of

Decades of laws and court rulings had left millions of American workers at the mercy of their employers. Under provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, promoted by Secretary of Labor

The New Deal's pro-labor legislation fueled a national labor movement in which Pennsylvanians played a leading role. When the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company refused to abide by a National Labor Relations Board's ruling, the case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which in a precedent-setting decision,

Mobilized by wage cuts and devastating unemployment, workers across the Commonwealth joined unions, engaged in public protests and strikes, marched on Harrisburg, elected pro-labor candidates to public offices, and struggled for a living wage and worker rights. Beginning in 1935, the

Steel was one of the last major industries to hold out against unionization. Empowered by the Wagner Act, the

That May, U. S. Steel finally recognized SWOC as the bargaining agent for its workers. Not all steel companies, however, followed its example. Convinced that New Deal programs and the gains of labor were jeopardizing the nation's economic future, Pennsylvania conservatives mobilized voters, regaining control of state government in the election of 1938, and worked to turn back the rising tide of change. Abroad, fascism and world war represented new challenges that would soon engulf the state and the nation.