Chapter 2: The Army of the Potomac Pursues Lee into Pennsylvania

When General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia invaded Pennsylvania in June 1863, the principal Union army in the eastern theater of operations was the Army of the Potomac. Organized in the fall of 1861, the army contained many competent brigade, division, and corps commanders, but it had rarely tasted victory. Its first commander, Major General George B. McClellan, was a brilliant organizer and morale builder. He molded the army into an effective fighting force and in the spring of 1862 led it to the very gates of Richmond. Nevertheless, General Lee's counter offensive drove the Yankees back during the Seven Days' Battles.

Lee then moved north and in August 1862 defeated the Union Army of Virginia, which was reinforced by parts of McClellan's army, at the Second Battle of Manassas. When Lee invaded Maryland, a reluctant Abraham Lincoln again placed McClellan in command. On September 17, the armies bloodied each other at Antietam, and although Lee withdrew, McClellan failed to capitalize on the victory.

Disappointed over McClellan's failure to pursue Lee's troops, in early November 1862 Lincoln replaced McClellan with General Ambrose E. Burnside, who at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 17, suffered 12,000 casualties in fruitless assaults on Lee's entrenched regiments. General Joseph Hooker quickly replaced Burnside, and over the winter, rebuilt the army's morale.

In late April 1863, Hooker launched a brilliant offensive that took Lee by surprise. Then, just as he was on the verge of outmaneuvering Lee, Hooker suddenly pulled his advancing troops back into a defensive position, which enabled Lee to use Stonewall Jackson's troops to counterattack at the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1-3). Defeated decisively, Hooker pulled back to Fredericksburg, and this provided Lee a second opportunity to launch an invasion of the North.

In mid-June 1863, the Army of the Potomac, 120,000-strong just a month earlier, was down to less than 90,000 soldiers, as units that had joined for two years or nine months had completed their terms of service and gone home. Still, the army was a formidable array of veteran troops generally led by competent officers.

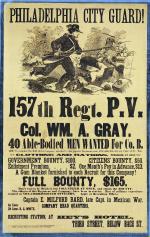

The backbone of the army, indeed of both Union and Confederate armies, was the regiment. On paper, a regiment of infantry consisted of ten companies with a strength of slightly more than 1,000 officers and men. By mid-1863, sickness, casualties, and detached duty soldiers meant that the average Yankee regiment consisted of only about 325 soldiers.

An average of four regiments made up a brigade. Two to four brigades comprised a division, and in the Union army, three divisions usually were grouped into a corps, which also had an attached brigade of artillery. The Army of the Potomac had seven infantry corps, one cavalry corps, and a Reserve Artillery of five brigades. (Cavalry regiments had twelve companies, and most of the artillery was organized into four- and six-gun batteries.)

While the Army of the Potomac was losing men, Hooker was in a bitter feud with the War Department. When Lee began moving north, Hooker asked permission to attack Lee's vulnerable rear by sending part of his army into the Cumberland Valley upriver from Harpers Ferry to sever Lee's communications with Virginia. Hooker wanted to use the Harpers Ferry garrison to bolster his troops, but the administration thought otherwise.

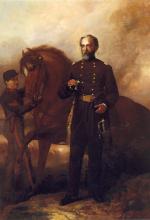

Hooker continued to complain, so President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton decided to make yet another change in commanders, even though a major battle could erupt at any time. On June 28, the War Department sacked General Hooker and replaced him with Major General George G. Meade, commander of the Fifth Corps and a native Pennsylvanian. Lincoln made it clear that Meade could not reject the order to take command, but he was to receive decision-making powers that the War Department had denied to Hooker.

Major General George G. Meade, commander of the Fifth Corps and a native Pennsylvanian. Lincoln made it clear that Meade could not reject the order to take command, but he was to receive decision-making powers that the War Department had denied to Hooker.

Upon taking command, Meade could count on a number of competent subordinates. One of his closest advisors and colleagues was his First Corps leader, Major General John F. Reynolds, another Pennsylvanian who was highly esteemed throughout the army.

Major General John F. Reynolds, another Pennsylvanian who was highly esteemed throughout the army.

In command of the Second Corps was yet another Pennsylvania officer, Major General Winfield S. Hancock, nicknamed "the Superb" for his previous battle performances. Other Pennsylvanians who would play crucial roles at the battle of Gettysburg included

Major General Winfield S. Hancock, nicknamed "the Superb" for his previous battle performances. Other Pennsylvanians who would play crucial roles at the battle of Gettysburg included  Brigadier General John W. Geary, a division commander in Henry Slocum's Twelfth Corps, and

Brigadier General John W. Geary, a division commander in Henry Slocum's Twelfth Corps, and  Colonel Strong Vincent, a brigade commander in Meade's old command, the Fifth Corps.

Colonel Strong Vincent, a brigade commander in Meade's old command, the Fifth Corps.

When Meade took command of the army, General George Sykes succeeded him as Fifth Corps commander. Major General Daniel E. Sickles, a politician turned general, headed the Third Corps, John Sedgwick the Sixth, and Oliver O. Howard the Eleventh. General Alfred Pleasonton was Meade's cavalry commander.

The Army of the Potomac began to move north shortly after Lee's troops moved into the Shenandoah Valley, paralleling the Rebels to the east to cover Washington against a sudden attack. Stanton sent reinforcements from the city garrison to bolster the field army, including an entire cavalry division and two brigades of the famed but under strength Pennsylvania Reserves, and its famous Bucktails (13th Pennsylvania Reserves).

Bucktails (13th Pennsylvania Reserves).

Concerned over the cavalry division's leadership, Pleasonton replaced the division commander and both brigade leaders before it joined the army. As it moved through Hanover, Pennsylvania, on June 30, Jeb Stuart's Southern cavalry slammed into its rearguard, igniting a full-scale battle. There, new division commander

Hanover, Pennsylvania, on June 30, Jeb Stuart's Southern cavalry slammed into its rearguard, igniting a full-scale battle. There, new division commander Judson Kilpatrick fought Stuart to a standstill.

Judson Kilpatrick fought Stuart to a standstill.

The Union Cavalry Corps' aggressive new leadership paid off throughout the latter stages of the Gettysburg Campaign. Brigadier General John Buford, in command of the First Division of the corps, scouted to Gettysburg on June 30 and decided to hold the town against a Confederate infantry force that approached from the west. His decision was among those that ultimately led both commanders to move their troops toward that Adams County crossroads.

On July 2, as the main armies were locked in combat, a scouting party led by Captain Ulric Dahlgren charged into Greencastle and scattered a smaller Rebel detachment. Dahlgren captured some dispatches between Lee and President Jefferson Davis that he quickly forwarded to army headquarters. These provided Meade vital information about his foe.

Captain Ulric Dahlgren charged into Greencastle and scattered a smaller Rebel detachment. Dahlgren captured some dispatches between Lee and President Jefferson Davis that he quickly forwarded to army headquarters. These provided Meade vital information about his foe.

Unlike the conservative McClellan and other earlier commanders, Meade was a man of quick and decisive action. Believing that Washington was safe and that Lee had slowed his northward advance, Meade decided to concentrate the Union army and then try to lure Lee into battle. When Lee finally received word of Meade's appointment, he also concentrated his own scattered divisions. The result was a Convergence on Gettysburg and the great battle that followed.

Lee then moved north and in August 1862 defeated the Union Army of Virginia, which was reinforced by parts of McClellan's army, at the Second Battle of Manassas. When Lee invaded Maryland, a reluctant Abraham Lincoln again placed McClellan in command. On September 17, the armies bloodied each other at Antietam, and although Lee withdrew, McClellan failed to capitalize on the victory.

Disappointed over McClellan's failure to pursue Lee's troops, in early November 1862 Lincoln replaced McClellan with General Ambrose E. Burnside, who at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 17, suffered 12,000 casualties in fruitless assaults on Lee's entrenched regiments. General Joseph Hooker quickly replaced Burnside, and over the winter, rebuilt the army's morale.

In late April 1863, Hooker launched a brilliant offensive that took Lee by surprise. Then, just as he was on the verge of outmaneuvering Lee, Hooker suddenly pulled his advancing troops back into a defensive position, which enabled Lee to use Stonewall Jackson's troops to counterattack at the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1-3). Defeated decisively, Hooker pulled back to Fredericksburg, and this provided Lee a second opportunity to launch an invasion of the North.

In mid-June 1863, the Army of the Potomac, 120,000-strong just a month earlier, was down to less than 90,000 soldiers, as units that had joined for two years or nine months had completed their terms of service and gone home. Still, the army was a formidable array of veteran troops generally led by competent officers.

The backbone of the army, indeed of both Union and Confederate armies, was the regiment. On paper, a regiment of infantry consisted of ten companies with a strength of slightly more than 1,000 officers and men. By mid-1863, sickness, casualties, and detached duty soldiers meant that the average Yankee regiment consisted of only about 325 soldiers.

An average of four regiments made up a brigade. Two to four brigades comprised a division, and in the Union army, three divisions usually were grouped into a corps, which also had an attached brigade of artillery. The Army of the Potomac had seven infantry corps, one cavalry corps, and a Reserve Artillery of five brigades. (Cavalry regiments had twelve companies, and most of the artillery was organized into four- and six-gun batteries.)

While the Army of the Potomac was losing men, Hooker was in a bitter feud with the War Department. When Lee began moving north, Hooker asked permission to attack Lee's vulnerable rear by sending part of his army into the Cumberland Valley upriver from Harpers Ferry to sever Lee's communications with Virginia. Hooker wanted to use the Harpers Ferry garrison to bolster his troops, but the administration thought otherwise.

Hooker continued to complain, so President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton decided to make yet another change in commanders, even though a major battle could erupt at any time. On June 28, the War Department sacked General Hooker and replaced him with

Upon taking command, Meade could count on a number of competent subordinates. One of his closest advisors and colleagues was his First Corps leader,

In command of the Second Corps was yet another Pennsylvania officer,

When Meade took command of the army, General George Sykes succeeded him as Fifth Corps commander. Major General Daniel E. Sickles, a politician turned general, headed the Third Corps, John Sedgwick the Sixth, and Oliver O. Howard the Eleventh. General Alfred Pleasonton was Meade's cavalry commander.

The Army of the Potomac began to move north shortly after Lee's troops moved into the Shenandoah Valley, paralleling the Rebels to the east to cover Washington against a sudden attack. Stanton sent reinforcements from the city garrison to bolster the field army, including an entire cavalry division and two brigades of the famed but under strength Pennsylvania Reserves, and its famous

Concerned over the cavalry division's leadership, Pleasonton replaced the division commander and both brigade leaders before it joined the army. As it moved through

The Union Cavalry Corps' aggressive new leadership paid off throughout the latter stages of the Gettysburg Campaign. Brigadier General John Buford, in command of the First Division of the corps, scouted to Gettysburg on June 30 and decided to hold the town against a Confederate infantry force that approached from the west. His decision was among those that ultimately led both commanders to move their troops toward that Adams County crossroads.

On July 2, as the main armies were locked in combat, a scouting party led by

Unlike the conservative McClellan and other earlier commanders, Meade was a man of quick and decisive action. Believing that Washington was safe and that Lee had slowed his northward advance, Meade decided to concentrate the Union army and then try to lure Lee into battle. When Lee finally received word of Meade's appointment, he also concentrated his own scattered divisions. The result was a Convergence on Gettysburg and the great battle that followed.