Chapter Three: Confronting Modernity: Pennsylvania Artists in the Twentieth Century

"I'd rather be in Philadelphia" is generally believed to be the epitaph Philadelphia-born comedian W. C. Fields (1879-1946) chose for himself (although it isn't), reflecting the fact that he only marginally preferred life in the City of Brotherly Love to death itself. For much of the twentieth century Philadelphia has enjoyed, if that is the word, a reputation for complacent, comfortable conservatism, only to acquire, in the last quarter of the century, a reputation for violence, urban blight, and toughness. Artistically, the city suffered from the same reputation as a cultural backwater: "No artist of international reputation...born in Philadelphia has ever been able to live here, or, if he leaves...and returns, the bourgeois by whom the place is entirely overrun drive him out again." So wrote celebrated Pennsylvania illustrator Joseph Pennell in the 1920s.

Yet in reality not only Philadelphia, but Pennsylvania as a whole, maintained its artistic importance throughout the century. New York, on the other hand, long celebrated as the national capital of the arts, has been famed almost exclusively for its avant-garde. New York hosted the Armory Show of 1913 that introduced cubism to the United States and was the home of Greenwich Village bohemia and Abstract Expressionism after World War II. It also boasts many of the nation's great museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim.

Pennsylvania's artistic art scene was, and is today as complex as the state itself; it both affirms yet denies the wonders of modern industry, and praises yet questions the values of traditional culture. The work of three leading African-American Pennsylvania artists demonstrates this diversity. The primitivist Horace Pippin exemplifies his racially diverse community of West Chester. He affirmed traditional Christian religious values in his art, while calling attention to the horrors of World War I, glorifying John Brown and Abraham Lincoln, and attacking "Mr. Prejudice." The sculptures of

Horace Pippin exemplifies his racially diverse community of West Chester. He affirmed traditional Christian religious values in his art, while calling attention to the horrors of World War I, glorifying John Brown and Abraham Lincoln, and attacking "Mr. Prejudice." The sculptures of  Meta Warwick Fuller who lived most of her mature life as a doctor's wife in Connecticut, assert black pride and modernist artistic values.

Meta Warwick Fuller who lived most of her mature life as a doctor's wife in Connecticut, assert black pride and modernist artistic values.  Laura Wheeling Waring painted leading African Americans who could serve as models for an integrated society. She participated in Harlem's famous black "Renaissance" of the 1920s, while spending most of her life teaching at Pennsylvania's black Cheyney University.

Laura Wheeling Waring painted leading African Americans who could serve as models for an integrated society. She participated in Harlem's famous black "Renaissance" of the 1920s, while spending most of her life teaching at Pennsylvania's black Cheyney University.

In the early twentieth century, Peter Widener, Henry Frick, Andrew Carnegie, Albert C. Barnes, and other wealthy Pennsylvanians amassed impressive collections of classic and contemporary arts, some of which were displayed in new museums constructed in Pittsburgh, New York, and on the Benjamin Franklin Boulevard in Philadelphia by

Henry Frick, Andrew Carnegie, Albert C. Barnes, and other wealthy Pennsylvanians amassed impressive collections of classic and contemporary arts, some of which were displayed in new museums constructed in Pittsburgh, New York, and on the Benjamin Franklin Boulevard in Philadelphia by  Philippe Cret and other leading architects of the day. In 1937, Pittsburgh's Andrew W. Mellon founded and endowed the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Philippe Cret and other leading architects of the day. In 1937, Pittsburgh's Andrew W. Mellon founded and endowed the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

A national center of art through most of the nineteenth century, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, (PAFA) developed a reputation for conservatism after it forced

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, (PAFA) developed a reputation for conservatism after it forced  Thomas Eakins to resign in 1886, in part for using male nude models in mixed classes of men and women, but also because his titanic personality did not work well with either his colleagues or a regular curriculum. One of his successors, Thomas Anschutz, a drawing instructor from 1886 until his death in 1912, moved forward with trends in modern art. Among his many pupils were the five Pennsylvania members of the eight-man "Ashcan School" - so they were sneered at by critics before they adopted the name with pride - Robert Henri, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens of Philadelphia, John Sloan of Lock Haven, and George Luks of Williamsport.

Thomas Eakins to resign in 1886, in part for using male nude models in mixed classes of men and women, but also because his titanic personality did not work well with either his colleagues or a regular curriculum. One of his successors, Thomas Anschutz, a drawing instructor from 1886 until his death in 1912, moved forward with trends in modern art. Among his many pupils were the five Pennsylvania members of the eight-man "Ashcan School" - so they were sneered at by critics before they adopted the name with pride - Robert Henri, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens of Philadelphia, John Sloan of Lock Haven, and George Luks of Williamsport.

All of these artists began as newspaper illustrators, and came into their own in the first decade of the twentieth century. While their techniques were reminiscent of Eakins, their subject matter was that of the urban beat reporter and their palettes were more colorful. Their paintings of urban workers and neighborhoods, the poor, circuses and actors, led conservative critics to call this group a "revolutionary black [evil] gang" and the "apostles of ugliness." They too left Pennsylvania for New York, where they joined the eight's remaining three - Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson, and Arthur B. Davies.

In the twentieth century, Pittsburgh also attracted artists who were drawn by the city's smoke-drenched industrial landscape and by local art patrons. Founded in 1910, Associated Artists of Pittsburgh is the nation's second oldest artists' association. Ernest Lawson, Collin Campbell Cooper, and others came to paint Pittsburgh. Here, too, the Carnegie Museum of Arts hosted annual international exhibitions juried by prominent American artists that featured contemporary art.

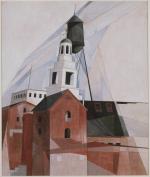

In Philadelphia, PAFA's 1921 "Exhibition of Paintings Showing the Latest Tendencies in Art" featured more than 280 works by 88 contemporary American artists, including Pennsylvanians Arthur B. Carles, John Marin, Charles Demuth, and

Charles Demuth, and  Charles Sheeler. Demuth (whose house in Lancaster is a museum of his work) and Sheeler painted geometrical structures which many interpret as praise of the machine and modernity, while others see in their visions critique of their monotony. Critic Thomas Craven wrote of "The Awakening of the Academy" in The Dial (June, 1921): "The Philadelphia Academy is to be commended for its new vision; it abandoned its traditional judgment that art should be a representation of material phenomenon, and invited to its halls a group of painters who have at least one interest in common, the knowledge that art is based on design and not on natural imitation. . . . The future of American art will certainly repose in a number of men represented at Philadelphia, not in the illustrators, imitators, and literalists of fashionable exploitation." From 1916 to 1952, PAFA also supported a summer school at

Charles Sheeler. Demuth (whose house in Lancaster is a museum of his work) and Sheeler painted geometrical structures which many interpret as praise of the machine and modernity, while others see in their visions critique of their monotony. Critic Thomas Craven wrote of "The Awakening of the Academy" in The Dial (June, 1921): "The Philadelphia Academy is to be commended for its new vision; it abandoned its traditional judgment that art should be a representation of material phenomenon, and invited to its halls a group of painters who have at least one interest in common, the knowledge that art is based on design and not on natural imitation. . . . The future of American art will certainly repose in a number of men represented at Philadelphia, not in the illustrators, imitators, and literalists of fashionable exploitation." From 1916 to 1952, PAFA also supported a summer school at  Chester Springs, where aspiring artists painted realistic images of animals, human beings (both models and country folk), old buildings, and the local countryside.

Chester Springs, where aspiring artists painted realistic images of animals, human beings (both models and country folk), old buildings, and the local countryside.

Pennsylvanians also participated in the major post-World War II art movements. Abstract expressionist Franz Kline of Wilkes-Barre began by painting realistic images of the gritty landscape of his native anthracite coal region, but earned international fame for the huge black-and-white abstractions that he frequently named after places in northeastern Pennsylvania. His work can be seen to embody both the power and desolation of its land and the people. The name of Pittsburgh's Andy Warhol is most associated with "pop" art, the serial paintings of objects such as Campbell's Soup Cans or images of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe. Just as Kline moved to New York to join fellow Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock, Willem DeKooning, and Mark Rothko in the bohemian Greenwich Village of the 1950s, Warhol relocated to New York clubs a decade later and made the city his own.

Franz Kline of Wilkes-Barre began by painting realistic images of the gritty landscape of his native anthracite coal region, but earned international fame for the huge black-and-white abstractions that he frequently named after places in northeastern Pennsylvania. His work can be seen to embody both the power and desolation of its land and the people. The name of Pittsburgh's Andy Warhol is most associated with "pop" art, the serial paintings of objects such as Campbell's Soup Cans or images of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe. Just as Kline moved to New York to join fellow Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock, Willem DeKooning, and Mark Rothko in the bohemian Greenwich Village of the 1950s, Warhol relocated to New York clubs a decade later and made the city his own.

Many of Warhol's works may be seen in his museum, a reconverted factory on Pittsburgh's north side. A few blocks away is the Mattress Factory, one of the few museums in the world devoted to Installation Art, which occupies several buildings in this recovering urban neighborhood. Here, visitors may find themselves in a room where electric lights and beeps travel along walls, in a cellar full of sculpture made from junk, or in a room where an artist, either live or on film, is part of an art exhibit that might contain abstract sculptures, ordinary furniture, or both.

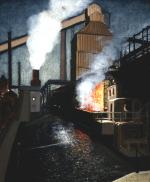

While some Pennsylvanians were painting pastoral scenes or abstract compositions, others dedicated themselves to the state's industrial might. Many of these works, which are set in the furnaces and steel towns of the Pittsburgh region, may be found in the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg or the Steidle Museum at the Pennsylvania State University. Greensburg's Museum features two suites of rooms: one on Pennsylvania landscapes of the nineteenth century, and the other on industrial depictions of Pennsylvania. At the Steidle, one can see works by Roy Hilton, Edmund Ashe, Carrie Pattison, Aaron Harry Gorson, Alan Thompson, Christopher Walker, and other Pennsylvania artists who painted industrial life in all its variety. While showing the devastation of the landscape, they also found beauty in steel mills and cityscapes and stressed the heroism and resilience of the Pennsylvanians who worked in the mines and factories.

Pennsylvanians have not only been the subjects of art; millions of them are art appreciators themselves, some without even knowing it. Everyone in America has seen the reverse of the Lincoln penny, designed by Frank Gasparro, and many have purchased the patriotic medallions he designed of Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, and other prominent Americans. Coins are in fact sculptures (the manufacturing process reduces the size) that convey the nation's sense of continuity with its heroic past.

Frank Gasparro, and many have purchased the patriotic medallions he designed of Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, and other prominent Americans. Coins are in fact sculptures (the manufacturing process reduces the size) that convey the nation's sense of continuity with its heroic past.

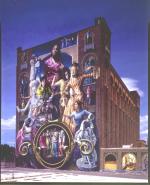

Another instance of bringing art to the public is The Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. Since the 1980s, Philadelphia artists (and sometimes school children) have executed more than 2,300 murals that now adorn city walls. The Program, begun in 1984 by Jane Golden, who came back east from Los Angeles where she had helped that city launch a similar program to combat gang violence and graffiti, is the nation's most extensive. It has been the model for similar programs in Pittsburgh, Pottsville, York, and Harrisburg.

The murals are as diverse as the community and its viewpoints. Murals of African Americans, for example, honor black servicemen, political activist Malcolm X, actor and singer Paul Robeson, sports figures Jackie Robinson and Julius Erving, and singer Patti LaBelle. Although this mural is not a MAP project, a German restaurant in Center City boasts a portrait of King Ludwig II and his castle. Frank Rizzo and Mario Lanza can be seen on walls in Italian South Philadelphia. Chinese children welcome visitors to Chinatown. People of all races join hands in Jane Golden's and Peter Pagast's 1998 "Peace Wall."

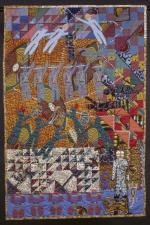

Some consider the quintessential Pennsylvania art form to be the quilt. Since colonial times, women, especially Pennsylvania Germans, have turned their quilt into works of art. Today, African-American and South Asian artisans are making quilts to assert their ethnic identity and pride. When Penn township celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1994, it cleverly designed a quilt with a dozen public buildings (some no longer extant) surrounded by the railroad tracks on which they depended for their creation and prosperity. Professional Artists, too, such as Shawn Quinlan, have also used quilts too to express their hopes for Pennsylvania. To celebrate the state's history and ethnic communities, thousands of twenty-first century Pennsylvanians are contributing to the Commonwealth's heritage as a leader in American art.

Yet in reality not only Philadelphia, but Pennsylvania as a whole, maintained its artistic importance throughout the century. New York, on the other hand, long celebrated as the national capital of the arts, has been famed almost exclusively for its avant-garde. New York hosted the Armory Show of 1913 that introduced cubism to the United States and was the home of Greenwich Village bohemia and Abstract Expressionism after World War II. It also boasts many of the nation's great museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim.

Pennsylvania's artistic art scene was, and is today as complex as the state itself; it both affirms yet denies the wonders of modern industry, and praises yet questions the values of traditional culture. The work of three leading African-American Pennsylvania artists demonstrates this diversity. The primitivist

In the early twentieth century, Peter Widener,

A national center of art through most of the nineteenth century, the

All of these artists began as newspaper illustrators, and came into their own in the first decade of the twentieth century. While their techniques were reminiscent of Eakins, their subject matter was that of the urban beat reporter and their palettes were more colorful. Their paintings of urban workers and neighborhoods, the poor, circuses and actors, led conservative critics to call this group a "revolutionary black [evil] gang" and the "apostles of ugliness." They too left Pennsylvania for New York, where they joined the eight's remaining three - Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson, and Arthur B. Davies.

In the twentieth century, Pittsburgh also attracted artists who were drawn by the city's smoke-drenched industrial landscape and by local art patrons. Founded in 1910, Associated Artists of Pittsburgh is the nation's second oldest artists' association. Ernest Lawson, Collin Campbell Cooper, and others came to paint Pittsburgh. Here, too, the Carnegie Museum of Arts hosted annual international exhibitions juried by prominent American artists that featured contemporary art.

In Philadelphia, PAFA's 1921 "Exhibition of Paintings Showing the Latest Tendencies in Art" featured more than 280 works by 88 contemporary American artists, including Pennsylvanians Arthur B. Carles, John Marin,

Pennsylvanians also participated in the major post-World War II art movements. Abstract expressionist

Many of Warhol's works may be seen in his museum, a reconverted factory on Pittsburgh's north side. A few blocks away is the Mattress Factory, one of the few museums in the world devoted to Installation Art, which occupies several buildings in this recovering urban neighborhood. Here, visitors may find themselves in a room where electric lights and beeps travel along walls, in a cellar full of sculpture made from junk, or in a room where an artist, either live or on film, is part of an art exhibit that might contain abstract sculptures, ordinary furniture, or both.

While some Pennsylvanians were painting pastoral scenes or abstract compositions, others dedicated themselves to the state's industrial might. Many of these works, which are set in the furnaces and steel towns of the Pittsburgh region, may be found in the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg or the Steidle Museum at the Pennsylvania State University. Greensburg's Museum features two suites of rooms: one on Pennsylvania landscapes of the nineteenth century, and the other on industrial depictions of Pennsylvania. At the Steidle, one can see works by Roy Hilton, Edmund Ashe, Carrie Pattison, Aaron Harry Gorson, Alan Thompson, Christopher Walker, and other Pennsylvania artists who painted industrial life in all its variety. While showing the devastation of the landscape, they also found beauty in steel mills and cityscapes and stressed the heroism and resilience of the Pennsylvanians who worked in the mines and factories.

Pennsylvanians have not only been the subjects of art; millions of them are art appreciators themselves, some without even knowing it. Everyone in America has seen the reverse of the Lincoln penny, designed by

Another instance of bringing art to the public is The Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. Since the 1980s, Philadelphia artists (and sometimes school children) have executed more than 2,300 murals that now adorn city walls. The Program, begun in 1984 by Jane Golden, who came back east from Los Angeles where she had helped that city launch a similar program to combat gang violence and graffiti, is the nation's most extensive. It has been the model for similar programs in Pittsburgh, Pottsville, York, and Harrisburg.

The murals are as diverse as the community and its viewpoints. Murals of African Americans, for example, honor black servicemen, political activist Malcolm X, actor and singer Paul Robeson, sports figures Jackie Robinson and Julius Erving, and singer Patti LaBelle. Although this mural is not a MAP project, a German restaurant in Center City boasts a portrait of King Ludwig II and his castle. Frank Rizzo and Mario Lanza can be seen on walls in Italian South Philadelphia. Chinese children welcome visitors to Chinatown. People of all races join hands in Jane Golden's and Peter Pagast's 1998 "Peace Wall."

Some consider the quintessential Pennsylvania art form to be the quilt. Since colonial times, women, especially Pennsylvania Germans, have turned their quilt into works of art. Today, African-American and South Asian artisans are making quilts to assert their ethnic identity and pride. When Penn township celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1994, it cleverly designed a quilt with a dozen public buildings (some no longer extant) surrounded by the railroad tracks on which they depended for their creation and prosperity. Professional Artists, too, such as Shawn Quinlan, have also used quilts too to express their hopes for Pennsylvania. To celebrate the state's history and ethnic communities, thousands of twenty-first century Pennsylvanians are contributing to the Commonwealth's heritage as a leader in American art.