![header=[Marker Text] body=[One of the greatest pitchers in baseball history. With the Philadelphia Athletics "Rube" Waddell led the American League in strikeouts 6 straight years, topping 20 wins in each of his first 4 years. During his career he won 193 games. He was known for his colorful and eccentric personality and was one of baseball's first true matinee idols. Born in Bradford, PA, and raised here in Prospect, Waddell was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-C-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a0e0-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

George Edward Waddell

Region:

Pittsburgh Region

County:

Butler

Marker Location:

Route 488, next to Fire Hall, Prospect

Dedication Date:

July 6, 2003

Behind the Marker

-Philadelphia Phillies' Manager Connie Mack

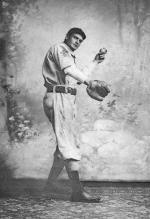

He was a problem child in an athlete's strapping frame. And a century after his stardom, Rube Waddell remains one of baseball's tragic enigmas. Blessed with a left arm the likes of which the game had never seen, he was also cursed with an undisciplined free spirit that haunted him. Contemporaries often viewed him as a colorful eccentric, but hindsight paints a darker picture. Waddell was a troubled man who drifted through much of his life in an alcoholic haze - Sporting News once called him a "souse paw" - suffering from intermittent bouts of mental illness.

Put a baseball in his hand, however, and Rube Waddell could be dazzling. One of the game's first power pitchers, he was a fire-baller with a devastating curve in an era before the strikeout king was fully appreciated. He was also one of three Hall of Fame starters for manager Connie Mack's fledgling Philadelphia Athletics in the first decade of the twentieth century. Waddell led the American League in strikeouts for six consecutive seasons, setting a major league mark of 349 in 1904 that stood for the next sixty-one years. In 1902, he became the first pitcher to strike out the side on the minimum nine pitches.

Born in 1876 in the northwestern Pennsylvania town of Bradford, George Edward Waddell avoided the schoolhouse as much as possible, but his sister recalled that "I could always find him playing ball, fishing, or following fire engines." By eighteen, he was pitching semi-pro ball in Butler. He quickly established a reputation for going the distance on the mound and in local taverns, and his child-like - some might argue eccentric - habits earned him the reputation as baseball's original flake. Waddell regularly delayed the start of games for a round of marbles with kids outside the park, disappeared between starts to go fishing, and turned up in firehouses in every American League city.

"He always wore a red undershirt," Mack recalled, "so that when the fire bell rang he could pull off his coat, thus exposing his crimson credentials, and gallop off to the blaze." During games, opponents would hold up stuffed animals and children's toys to rattle the concentration of a player whose antics were wildly unpredictable. After one particularly hard-earned victory, he turned cartwheels back to the dugout.

In the off-season, Waddell added to his quirky legend with unconventional activities that both amazed and alarmed. Joe Finnegan, the publicist for a theater company that Waddell for a while toured with, also added his own stories to enhance Waddell's celebrity. Waddell, it was reported, wrestled alligators in Florida, played football in Michigan, tended bar, accidentally shot a friend through the hand with a gun, and assaulted his second wife's step father with a flat iron. And he spent more than a few nights in jail.

Future Hall of Famer Sam Crawford, a teammate in the minors, loved to relate how Waddell sometimes poured ice water over his pitching arm and shoulder before a game to, quite literally, cool himself down. "I've got so much speed today," Waddell would complain, "I'll burn up the catcher's glove if I don't let up a bit."

Despite the ice, Waddell had a knack for burning up opposition hitters, and in 1897, the Louisville Colonels offered him his first sip of the Major leagues. It didn't last long. Fined $50 for drinking, Waddell stormed off after just two games. He returned two seasons later, then bounced up and down between the minors and National League, all the while showing spurts of brilliance. In 1902, Waddell landed with the A's when Mack gambled that he could rein in Waddell's erratic behaviors and coax to the surface the gold he knew lay buried in Waddell's left arm.

For several years Mack succeeded, in part by carefully doling out Waddell's pay in dollar bills on an as-needed basis. (Mack used this method to try and discourage Waddell from blowing his salary on alcohol and other enticements). Waddell repaid his manager handsomely. Along with fellow Pennsylvanians Chief Bender and

Chief Bender and  Eddie Plank, he solidified one of the most efficient rotations in baseball history. In his first four seasons with the club, Waddell contributed 24, 21, 25 and a league-leading 27 victories. In perhaps his most valiant performance, he bested Cy Young, baseball's most winning pitcher, in a twenty-inning classic on July 4, 1905. But toward the end of that season, Waddell hurt his arm in a silly fight over a straw hat with a teammate, and missed the final month of play and the World Series against

Eddie Plank, he solidified one of the most efficient rotations in baseball history. In his first four seasons with the club, Waddell contributed 24, 21, 25 and a league-leading 27 victories. In perhaps his most valiant performance, he bested Cy Young, baseball's most winning pitcher, in a twenty-inning classic on July 4, 1905. But toward the end of that season, Waddell hurt his arm in a silly fight over a straw hat with a teammate, and missed the final month of play and the World Series against  Christy Mathewson and the Giants. He was never the same pitcher again.

Christy Mathewson and the Giants. He was never the same pitcher again.

Pressured by Waddell's teammates who were angered at his unreliability and a dispute over pay, Mack finally sold the big lefthander to the St. Louis Browns before the 1908 season. In July, Waddell humbled his former teammates, tying a major league mark by fanning sixteen players. Six weeks later, he whiffed seventeen Senators in ten innings, out-flaming Hall of Famer Walter Johnson in a 2-1 gem. By 1910, with a career record of 193-143, Waddell had pitched and drunk himself back to the minors where he continued to wind down until 1913, the year before his death.

To Waddell's credit, his end began in heroic fashion, straight from the pages of his unconventional life. After the 1911 season, Waddell went to live in Hickman, Kentucky. When a nearby dam collapsed in the spring of 1912, he flew into action, working for hours in frigid waters to pile sandbags against the rising flood waters. But the effort took its toll. Waddell's health deteriorated, and in late 1913, he was found wandering the streets of St. Louis, suffering from tuberculosis. He died in 1914 - on April Fool's Day - in a sanitarium in Texas. "There was no better pitcher than he when he was in form," The New York Times wrote in his obituary, "but he, as well as managers and club owners, was aware of his own inability to resist temptation."

Rube Waddell was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1946.

"He had more stuff than any pitcher I ever saw. He had everything but a sense of responsibility."

-Philadelphia Phillies' Manager Connie Mack

He was a problem child in an athlete's strapping frame. And a century after his stardom, Rube Waddell remains one of baseball's tragic enigmas. Blessed with a left arm the likes of which the game had never seen, he was also cursed with an undisciplined free spirit that haunted him. Contemporaries often viewed him as a colorful eccentric, but hindsight paints a darker picture. Waddell was a troubled man who drifted through much of his life in an alcoholic haze - Sporting News once called him a "souse paw" - suffering from intermittent bouts of mental illness.

Put a baseball in his hand, however, and Rube Waddell could be dazzling. One of the game's first power pitchers, he was a fire-baller with a devastating curve in an era before the strikeout king was fully appreciated. He was also one of three Hall of Fame starters for manager Connie Mack's fledgling Philadelphia Athletics in the first decade of the twentieth century. Waddell led the American League in strikeouts for six consecutive seasons, setting a major league mark of 349 in 1904 that stood for the next sixty-one years. In 1902, he became the first pitcher to strike out the side on the minimum nine pitches.

Born in 1876 in the northwestern Pennsylvania town of Bradford, George Edward Waddell avoided the schoolhouse as much as possible, but his sister recalled that "I could always find him playing ball, fishing, or following fire engines." By eighteen, he was pitching semi-pro ball in Butler. He quickly established a reputation for going the distance on the mound and in local taverns, and his child-like - some might argue eccentric - habits earned him the reputation as baseball's original flake. Waddell regularly delayed the start of games for a round of marbles with kids outside the park, disappeared between starts to go fishing, and turned up in firehouses in every American League city.

"He always wore a red undershirt," Mack recalled, "so that when the fire bell rang he could pull off his coat, thus exposing his crimson credentials, and gallop off to the blaze." During games, opponents would hold up stuffed animals and children's toys to rattle the concentration of a player whose antics were wildly unpredictable. After one particularly hard-earned victory, he turned cartwheels back to the dugout.

In the off-season, Waddell added to his quirky legend with unconventional activities that both amazed and alarmed. Joe Finnegan, the publicist for a theater company that Waddell for a while toured with, also added his own stories to enhance Waddell's celebrity. Waddell, it was reported, wrestled alligators in Florida, played football in Michigan, tended bar, accidentally shot a friend through the hand with a gun, and assaulted his second wife's step father with a flat iron. And he spent more than a few nights in jail.

Future Hall of Famer Sam Crawford, a teammate in the minors, loved to relate how Waddell sometimes poured ice water over his pitching arm and shoulder before a game to, quite literally, cool himself down. "I've got so much speed today," Waddell would complain, "I'll burn up the catcher's glove if I don't let up a bit."

Despite the ice, Waddell had a knack for burning up opposition hitters, and in 1897, the Louisville Colonels offered him his first sip of the Major leagues. It didn't last long. Fined $50 for drinking, Waddell stormed off after just two games. He returned two seasons later, then bounced up and down between the minors and National League, all the while showing spurts of brilliance. In 1902, Waddell landed with the A's when Mack gambled that he could rein in Waddell's erratic behaviors and coax to the surface the gold he knew lay buried in Waddell's left arm.

For several years Mack succeeded, in part by carefully doling out Waddell's pay in dollar bills on an as-needed basis. (Mack used this method to try and discourage Waddell from blowing his salary on alcohol and other enticements). Waddell repaid his manager handsomely. Along with fellow Pennsylvanians

Pressured by Waddell's teammates who were angered at his unreliability and a dispute over pay, Mack finally sold the big lefthander to the St. Louis Browns before the 1908 season. In July, Waddell humbled his former teammates, tying a major league mark by fanning sixteen players. Six weeks later, he whiffed seventeen Senators in ten innings, out-flaming Hall of Famer Walter Johnson in a 2-1 gem. By 1910, with a career record of 193-143, Waddell had pitched and drunk himself back to the minors where he continued to wind down until 1913, the year before his death.

To Waddell's credit, his end began in heroic fashion, straight from the pages of his unconventional life. After the 1911 season, Waddell went to live in Hickman, Kentucky. When a nearby dam collapsed in the spring of 1912, he flew into action, working for hours in frigid waters to pile sandbags against the rising flood waters. But the effort took its toll. Waddell's health deteriorated, and in late 1913, he was found wandering the streets of St. Louis, suffering from tuberculosis. He died in 1914 - on April Fool's Day - in a sanitarium in Texas. "There was no better pitcher than he when he was in form," The New York Times wrote in his obituary, "but he, as well as managers and club owners, was aware of his own inability to resist temptation."

Rube Waddell was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1946.