![header=[Marker Text] body=[While living here, he was an Underground Railroad agent who helped slaves escape and kept records so relatives could find them later. A wealthy coal merchant, Still also helped found the first Black YMCA.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3EB-139-1-A-10F-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a4i2-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

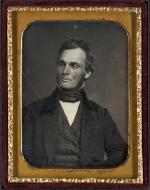

William Still

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

244 South 12th Street, Philadelphia

Dedication Date:

July 1991

Behind the Marker

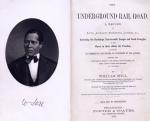

It was this resolution, passed at the last meeting of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in May 1871, that would result in the publication of one of the greatest collection of testimonies in American history: William Still's The Underground Rail Road. Published in 1872, The Underground Railroad remains the single most important collection of stories of the men and women who escaped from slavery in the decades preceding the outbreak of the Civil War, and it was compiled by a man who had served as one of that clandestine organization’s most important conductors.

Still was born in 1821 to former slaves. After his father purchased his freedom in Maryland and his mother escaped, the couple fled and changed their name from “Steel” to “Still” to avoid recapture. The youngest of eighteen children, William Still grew up on a small farm in Medford, New Jersey. He left home at the age of twenty to labor on neighboring farms and in 1844 traveled to Philadelphia in search of work. In 1847, he obtained employment as a janitor and clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (PAS).

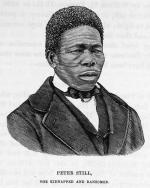

During the summer of 1850, Still interviewed an ex-slave named Peter, who after purchasing his own freedom had traveled to Philadelphia in search of his family. While listening to the man’s story, Still realized that Peter was his brother, separated from the family forty years earlier, when their mother had fled from Maryland. After this fateful encounter, Still began to document and preserve the stories of the men and women who were fleeing from the South and to help reunite families torn apart by slavery.

After the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society reorganized its Vigilance Committee in 1852, Still became its first corresponding secretary and chairman. For the next eight years, he coordinated escapes with numerous activists, including Harriet Tubman, and documented the stories of nearly 650 runaways.

Still was not the first person to collect such stories. Robert Purvis, a prominent African-American abolitionist, who had organized the original Philadelphia Vigilance Committee in 1837, had also documented the accounts of fugitives aided by the committee. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, however, aiding fugitive slaves carried with it a potential six-month jail sentence, a $1,000 fine, and an additional civil liability of up to $1,000. To eliminate the records that might be used in their recapture and to protect himself from prosecution, Purvis destroyed all of his records.

Robert Purvis, a prominent African-American abolitionist, who had organized the original Philadelphia Vigilance Committee in 1837, had also documented the accounts of fugitives aided by the committee. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, however, aiding fugitive slaves carried with it a potential six-month jail sentence, a $1,000 fine, and an additional civil liability of up to $1,000. To eliminate the records that might be used in their recapture and to protect himself from prosecution, Purvis destroyed all of his records.

Despite the steep penalties and the risks of what might happen should the records fall into the wrong hands, Still continued his clandestine work with the PAS, and continued to collect stories.

During the Civil War, Still ran a small coal and ice yard and supplied the Union Army at Camp William Penn, the state’s principal training site for black troops just north of Philadelphia, under a government contract. He also stepped up his activities in support of black civil rights in Philadelphia. In 1859, Still had launched a campaign for the desegregation of Philadelphia railway cars. In 1861, PAS's Social, Civil, and Statistical Association drafted a petition against the racial discrimination of railway companies and collected 300 signatures from prominent Philadelphians. Still continued the struggle until the Pennsylvania Legislature passed an act in 1867 prohibiting segregation in public transportation statewide. The same year, Still published his a narrative of his fight: Struggle for the Civil Rights of the Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars.

Camp William Penn, the state’s principal training site for black troops just north of Philadelphia, under a government contract. He also stepped up his activities in support of black civil rights in Philadelphia. In 1859, Still had launched a campaign for the desegregation of Philadelphia railway cars. In 1861, PAS's Social, Civil, and Statistical Association drafted a petition against the racial discrimination of railway companies and collected 300 signatures from prominent Philadelphians. Still continued the struggle until the Pennsylvania Legislature passed an act in 1867 prohibiting segregation in public transportation statewide. The same year, Still published his a narrative of his fight: Struggle for the Civil Rights of the Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars.

After the end of slavery and subsequent ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 and the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society decided to close its doors. At its final meeting in May 1871, the remaining members passed the resolution quoted above, calling for William Still to publish his records and reminiscences.

Because of the dangers associated with maintaining records after passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, most abolitionists working with the Underground Railroad had destroyed their records, and made no written record of their activities after that. Still, however, had kept his accounts, and after the outbreak of Civil War in 1861, had secreted them away in the loft of Philadelphia's Lebanon Cemetery building. It was these testimonies that he used, along with newspaper clippings, legal documents, and correspondence, to write a book that told the story of the Underground Railroad from the perspective of the heroic men and women who had escaped from slavery rather than from the perspective of the abolitionists who aided them. And he did this, as he wrote in the introduction, "to bring the doings of the U.G.R.R. before the public in the most truthful manner."

before the public in the most truthful manner."

Published in 1872, The Underground Rail Road remains the single best source of African-American experiences on the Underground Railroad. Contemporaries recognized the importance of Still’s work immediately. In April 1872, shortly after the book’s publication, famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison wrote to Still that he hoped “the sale of your work will be widely extended…for the enlightenment of the rising generation as to the inherent cruelty of the defunct slave system.”

In the decades following the Civil War, Still cemented his position as one of Philadelphia’s most successful African-American businessmen. A leader of the city's black community, Still worked the remainder of his life for the betterment of African Americans in Philadelphia, and as a spokesman for economic self-help. As president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, he expanded the group’s charitable works. He also served as president of the Berean Building and Loan Association, aiding people in purchasing homes, and ran the Home for Aged and Infirm Persons. Still also traveled and lectured to promote The Underground Railroad until his death in 1902.

Whereas, The position of William Still in the vigilance committee connected with the "Underground Rail Road," as its corresponding secretary, and chairman of its active sub-committee, gave him peculiar facilities for collecting interesting facts pertaining to this branch of the anti-slavery service; therefore

Resolved, That the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society request him to compile and publish his personal reminiscences and experiences relating to the "Underground Rail Road."

It was this resolution, passed at the last meeting of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in May 1871, that would result in the publication of one of the greatest collection of testimonies in American history: William Still's The Underground Rail Road. Published in 1872, The Underground Railroad remains the single most important collection of stories of the men and women who escaped from slavery in the decades preceding the outbreak of the Civil War, and it was compiled by a man who had served as one of that clandestine organization’s most important conductors.

Still was born in 1821 to former slaves. After his father purchased his freedom in Maryland and his mother escaped, the couple fled and changed their name from “Steel” to “Still” to avoid recapture. The youngest of eighteen children, William Still grew up on a small farm in Medford, New Jersey. He left home at the age of twenty to labor on neighboring farms and in 1844 traveled to Philadelphia in search of work. In 1847, he obtained employment as a janitor and clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (PAS).

During the summer of 1850, Still interviewed an ex-slave named Peter, who after purchasing his own freedom had traveled to Philadelphia in search of his family. While listening to the man’s story, Still realized that Peter was his brother, separated from the family forty years earlier, when their mother had fled from Maryland. After this fateful encounter, Still began to document and preserve the stories of the men and women who were fleeing from the South and to help reunite families torn apart by slavery.

After the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society reorganized its Vigilance Committee in 1852, Still became its first corresponding secretary and chairman. For the next eight years, he coordinated escapes with numerous activists, including Harriet Tubman, and documented the stories of nearly 650 runaways.

Still was not the first person to collect such stories.

Despite the steep penalties and the risks of what might happen should the records fall into the wrong hands, Still continued his clandestine work with the PAS, and continued to collect stories.

During the Civil War, Still ran a small coal and ice yard and supplied the Union Army at

After the end of slavery and subsequent ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 and the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society decided to close its doors. At its final meeting in May 1871, the remaining members passed the resolution quoted above, calling for William Still to publish his records and reminiscences.

Because of the dangers associated with maintaining records after passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, most abolitionists working with the Underground Railroad had destroyed their records, and made no written record of their activities after that. Still, however, had kept his accounts, and after the outbreak of Civil War in 1861, had secreted them away in the loft of Philadelphia's Lebanon Cemetery building. It was these testimonies that he used, along with newspaper clippings, legal documents, and correspondence, to write a book that told the story of the Underground Railroad from the perspective of the heroic men and women who had escaped from slavery rather than from the perspective of the abolitionists who aided them. And he did this, as he wrote in the introduction, "to bring the doings of the U.G.R.R.

Published in 1872, The Underground Rail Road remains the single best source of African-American experiences on the Underground Railroad. Contemporaries recognized the importance of Still’s work immediately. In April 1872, shortly after the book’s publication, famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison wrote to Still that he hoped “the sale of your work will be widely extended…for the enlightenment of the rising generation as to the inherent cruelty of the defunct slave system.”

In the decades following the Civil War, Still cemented his position as one of Philadelphia’s most successful African-American businessmen. A leader of the city's black community, Still worked the remainder of his life for the betterment of African Americans in Philadelphia, and as a spokesman for economic self-help. As president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, he expanded the group’s charitable works. He also served as president of the Berean Building and Loan Association, aiding people in purchasing homes, and ran the Home for Aged and Infirm Persons. Still also traveled and lectured to promote The Underground Railroad until his death in 1902.