![header=[Marker Text] body=[First U.S. foundation, Augustinian Order, 1796. In 1844 the original church here was burned during nativist riots. This and other violence led to a state law requiring police forces, 1845, and to the consolidation of the city and county, 1854.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3D2-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0n2f7-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

St. Augustine's Roman Catholic Church

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

200 block. N. Front St., 4th and Vine Streets Philadelphia

Dedication Date:

October 28, 1995

Behind the Marker

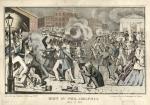

In May and then again in July 1844, violent urban riots raged across Philadelphia and its neighboring Southwark and Kensington townships as natives clashed with newcomers. The 1844 riots were part of a larger pattern of organized ethnic and religious violence tied to political nativism, or anti-immigrant sentiment, that was sweeping the nation. They also revealed deep-seated ethnic and religious differences in the City of Brotherly Love, the Commonwealth, and the nation. Known as the "Bible Riots" for their connection to a larger controversy in Philadelphia over public education, the clashes left twenty-five people dead, 100 injured, and dozens of buildings in ruin, including two Catholic churches: St. Michael's and St. Augustine's.

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia, like other Atlantic seaboard cities, had experienced a surge in population. Attracted to the city's burgeoning manufacturing base, waves of immigrant laborers settled in its working-class districts and neighboring townships, and competed with native-born workers for jobs, housing, and urban spaces. By the 1840s, a growing Irish and Catholic population resided in a city long dominated by mainstream Protestant congregations. The two Catholic churches burned in the 1844 rioting were strongholds of Catholic identity.

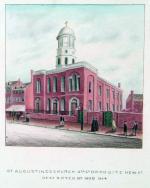

Founded in the late 1700s by the Brothers of the Order of Hermits of St. Augustine-better known as the Augustinians (O.S.A.)-St. Augustine's Catholic Church was the largest and most prominent Catholic church in the city after its construction in 1796. Built just three years after the great Yellow Fever outbreak of 1793, St. Augustine's was a symbol of renewed faith in Philadelphia's future-President George Washington was among the dignitaries who contributed to the subscription campaign-and of the city's growing Catholic population. (It was also closely associated with the Irish parishioners who attended Mass there on Sundays and sent their children to its parish school). A tall cupola added in 1829 made the imposing structure even more prominent-a fact not lost on the rioters in 1844.

In the early 1840s, Philadelphia's Catholics and the church hierarchy vocally protested the use of the Protestant bible, which attracted the attention of local nativists. On May 3, 1844, a long simmering dispute between Protestant and Catholic factions over the use of the King James Bible in public-school instruction spilled over into street violence and a brawl resulted in the death of four nativist marchers.

Calling on Philadelphians to defend themselves from "the bloody hand of the Pope" and alleging that Catholics had desecrated the American flag, bands of young nativist toughs marched into Kensington on May 7, then a township north of Philadelphia. When gunfire broke out, the nativists rioted, torching the Hibernia firehouse, thirty homes, and a market before local militia led by General George Cadwalader dispersed the crowd.

On May 8, the nativists took to the streets again. One group returned to Kensington, where they burned down St. Michael's Catholic Church at Second and Jefferson Streets, the Seminary of the Sisters of Charity, and several homes. Another mob gathered at St. Augustine's Catholic Church, threw stones at Mayor John Morin Scott as he pleaded for calm, and, ignoring the troops on guard, burned the church to the ground, cheering when the steeple fell.

Like the riots themselves, the burning of St. Augustine's Church is weighted with historical significance. Following the deadly summer, the friars recovered a judgment of $80,000-no small sum of money at the time-when they successfully sued the city of Philadelphia for failing to protect their property. The Augustinian order and local parishioners then rebuilt the church as a sign of Catholic resilience in the face of prejudice.

The rioting also led to the establishment of professional municipal police forces in Pennsylvania, as much to quell lawlessness as to keep warring factions apart. In the years that followed, an infant parochial-school system flourished in Philadelphia to educate Catholic youth and to defend the faith against its detractors. The rioting also contributed to the consolidation of city and county government in Philadelphia in 1854, in significant part to improve law enforcement.

Anti-immigrant feeling-and occasional rioting-continued to plague American cities, large and small. Across Pennsylvania and the Northeast, the fragmented alliances that supported the anti-immigrant agitation of 1844 coalesced into a formidable national force in the 1850s. Founded in 1845, the Native American Party-better known as the Know Nothing Party-attempted to exploit anti-immigrant fears, only to be drowned out by the larger sectional conflict over slavery and the coming Civil War. By 1856, it had all but disappeared. Nativism, and the resilient anti-immigrant sentiments that fueled the 1844 rioting, however, would continue to resurface over the next century and half of American life.

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia, like other Atlantic seaboard cities, had experienced a surge in population. Attracted to the city's burgeoning manufacturing base, waves of immigrant laborers settled in its working-class districts and neighboring townships, and competed with native-born workers for jobs, housing, and urban spaces. By the 1840s, a growing Irish and Catholic population resided in a city long dominated by mainstream Protestant congregations. The two Catholic churches burned in the 1844 rioting were strongholds of Catholic identity.

Founded in the late 1700s by the Brothers of the Order of Hermits of St. Augustine-better known as the Augustinians (O.S.A.)-St. Augustine's Catholic Church was the largest and most prominent Catholic church in the city after its construction in 1796. Built just three years after the great Yellow Fever outbreak of 1793, St. Augustine's was a symbol of renewed faith in Philadelphia's future-President George Washington was among the dignitaries who contributed to the subscription campaign-and of the city's growing Catholic population. (It was also closely associated with the Irish parishioners who attended Mass there on Sundays and sent their children to its parish school). A tall cupola added in 1829 made the imposing structure even more prominent-a fact not lost on the rioters in 1844.

In the early 1840s, Philadelphia's Catholics and the church hierarchy vocally protested the use of the Protestant bible, which attracted the attention of local nativists. On May 3, 1844, a long simmering dispute between Protestant and Catholic factions over the use of the King James Bible in public-school instruction spilled over into street violence and a brawl resulted in the death of four nativist marchers.

Calling on Philadelphians to defend themselves from "the bloody hand of the Pope" and alleging that Catholics had desecrated the American flag, bands of young nativist toughs marched into Kensington on May 7, then a township north of Philadelphia. When gunfire broke out, the nativists rioted, torching the Hibernia firehouse, thirty homes, and a market before local militia led by General George Cadwalader dispersed the crowd.

On May 8, the nativists took to the streets again. One group returned to Kensington, where they burned down St. Michael's Catholic Church at Second and Jefferson Streets, the Seminary of the Sisters of Charity, and several homes. Another mob gathered at St. Augustine's Catholic Church, threw stones at Mayor John Morin Scott as he pleaded for calm, and, ignoring the troops on guard, burned the church to the ground, cheering when the steeple fell.

Like the riots themselves, the burning of St. Augustine's Church is weighted with historical significance. Following the deadly summer, the friars recovered a judgment of $80,000-no small sum of money at the time-when they successfully sued the city of Philadelphia for failing to protect their property. The Augustinian order and local parishioners then rebuilt the church as a sign of Catholic resilience in the face of prejudice.

The rioting also led to the establishment of professional municipal police forces in Pennsylvania, as much to quell lawlessness as to keep warring factions apart. In the years that followed, an infant parochial-school system flourished in Philadelphia to educate Catholic youth and to defend the faith against its detractors. The rioting also contributed to the consolidation of city and county government in Philadelphia in 1854, in significant part to improve law enforcement.

Anti-immigrant feeling-and occasional rioting-continued to plague American cities, large and small. Across Pennsylvania and the Northeast, the fragmented alliances that supported the anti-immigrant agitation of 1844 coalesced into a formidable national force in the 1850s. Founded in 1845, the Native American Party-better known as the Know Nothing Party-attempted to exploit anti-immigrant fears, only to be drowned out by the larger sectional conflict over slavery and the coming Civil War. By 1856, it had all but disappeared. Nativism, and the resilient anti-immigrant sentiments that fueled the 1844 rioting, however, would continue to resurface over the next century and half of American life.