![header=[Marker Text] body=[The noted forester, conservationist and Governor of Pennsylvania two terms in 1923-27; 1931-35, had his ancestral home at Gray Towers, Milford. He is buried in this cemetery. Born in Connecticut, 1865 of a long line of pioneers of this region. Died on October 4, 1946. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3C8-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0m8e3-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

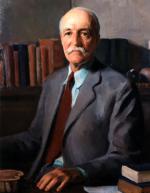

Gifford Pinchot [Politics]

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Pike

Marker Location:

U.S. 209 S of Milford

Dedication Date:

June 1, 1948

Behind the Marker

High above the Delaware River just north of Milford, in Pennsylvania's northeastern corner, stands "Grey Towers," present site of the Yale University School of Forestry, and former home of Gifford Pinchot, who after making his mark as America's premier forester at the turn of the twentieth century served two terms as the governor of Pennsylvania.

Born to money, Pinchot attended private schools in New York City, graduated from Yale in 1889, and then studied forestry in France and Germany, in programs that emphasized the scientific study of resources and government regulation to ensure long-term conservation of vital natural resources. In 1896, President Grover Cleveland appointed Pinchot to the National Forest Commission and then to head the Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. Pinchot retained this post under the Republican Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, under whom he headed the new National Forest Service.

After leaving Washington, Pinchot entered Pennsylvania politics. The conservative Republican machine defeated his bid for the United States Senate in 1914 and 1920, when he lost to Boies Penrose. In 1922, the year after Penrose died, Pinchot won the governorship by allying with the Mellon interests of Pittsburgh and the Pennsylvania Association of Manufacturers president Joseph Grundy.

Joseph Grundy.

Disguising his reform objectives, Pinchot ran on a platform calling for "economy and efficiency" and courted women voters with the help of his flamboyant wife, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, who joined him in putting up nearly all of the $118,000 his campaign cost. Once inaugurated, he fought hard for reforms.

fought hard for reforms.

In the 1920s, the control of the Republican Party in Pennsylvania was split between the Mellon/Grundy faction and the Vare machine in Philadelphia. Bill Vare, a tough working-class scrapper who had begun his life as a trash collector, then followed in his brothers' footsteps as the political boss of the city. Vare had opposed Pinchot in the governor's race, and the two would continue to clash for the rest of Vare's life.

political boss of the city. Vare had opposed Pinchot in the governor's race, and the two would continue to clash for the rest of Vare's life.

In January 1920, the manufacture and sale of alcohol became illegal when the Eighteenth Amendment became the law of the land. Pinchot was a strong Prohibitionist, but Philadelphia, under the Vare machine's leadership, so openly flaunted its disregard of the law that in 1924 President Calvin Coolidge loaned incoming Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick the services of Marine Corps Lieutenant Smedley Darlington Butler to clean up the city and enforce Prohibition.

After an initial flurry of highly publicized raids and prosecutions, Butler failed in his mission. Philadelphians and other Pennsylvanians liked their liquor, and the machine bosses liked the money it fed into their treasuries.

When the Pennsylvania legislature, which never voted for the measure, refused to provide funds to enforce the federal law, Pinchot obtained voluntary contributions from the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Pennsylvania's current liquor laws, with sales restricted to state stores, stem from his refusal in his second term to approve of private sales after Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

As governor, Pinchot pushed through as many reforms as the state legislature would permit. He instituted the Giant Power Survey Board to regulate the state's principal electric utilities, attempted to help Pennsylvania's miners during the national coal strike of 1922-23, and then investigated abusive and illegal actions during that strike of members of the

coal strike of 1922-23, and then investigated abusive and illegal actions during that strike of members of the  Pennsylvania State Police.

Pennsylvania State Police.

He streamlined state government, promoted education and attacked the state patronage system by reorganizing 139 separate agencies into fifteen departments headed by Cabinet officers, and instituting a state budget that standardized salaries and promotions under civil-service criteria. He also devised state employment retirement and old-age pension systems, and other reforms.

promoted education and attacked the state patronage system by reorganizing 139 separate agencies into fifteen departments headed by Cabinet officers, and instituting a state budget that standardized salaries and promotions under civil-service criteria. He also devised state employment retirement and old-age pension systems, and other reforms.

Forbidden from succeeding himself, Pinchot again ran for the United States Senate in 1926 but lost the Republican nomination to William Vare in a three-way primary that also included sitting Senator George Wharton Pepper. (It says much for the weakness of the Democratic Party at this time that despite this infighting, Democrat and former Secretary of Labor William Wilson could not defeat Vare in the general election, even after the attacks his own party had leveled against him.)

William Wilson could not defeat Vare in the general election, even after the attacks his own party had leveled against him.)

Pinchot took revenge by refusing to certify Vare's election, as the governor was empowered to do, charging it was corrupt. For three years, Pennsylvania's second Senate seat remained vacant as the United States Senate sorted things out. Finally, it ruled Vare's election invalid, and Governor

charging it was corrupt. For three years, Pennsylvania's second Senate seat remained vacant as the United States Senate sorted things out. Finally, it ruled Vare's election invalid, and Governor  John Fisher appointed Herbert Hoover's Secretary of Labor James Davis to the position, a victory for Mellon and Grundy and a source of satisfaction to Pinchot. In truth, the 1926 Senate election was no more corrupt than most in Pennsylvania: Vare simply lacked the respectable facade acceptable to men like Pinchot and the Mellons.

John Fisher appointed Herbert Hoover's Secretary of Labor James Davis to the position, a victory for Mellon and Grundy and a source of satisfaction to Pinchot. In truth, the 1926 Senate election was no more corrupt than most in Pennsylvania: Vare simply lacked the respectable facade acceptable to men like Pinchot and the Mellons.

In 1930, Pinchot was re-elected to a four-year term as governor by less than 50,000 votes out of over two million cast. To fight the Depression, Pinchot instituted massive road-paving projects, soon known as Pinchot Roads, throughout the state.

Pinchot Roads, throughout the state.

Outraged at the refusal of the state legislature to support relief measures for millions of unemployed Pennsylvanians in dire need, Pinchot in 1932 broke with his party and supported Franklin Roosevelt for president. Pinchot hoped his independence, support of government welfare programs, labor, and road building might propel him to the presidency, but the Republicans would not consider a renegade from one of the few states to support them in 1932.

After his term as governor, Pinchot spent much of the late 1930s fighting against his former friend, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, to keep the Forest Service autonomous from the newly formed Department of Conservation and Public Works. Best known today for his pioneering work in American forestry in the early 1900s, Pinchot was also an ambitious, courageous, and colorful governor. The "Great Forestor," however, never realized his ambition either to become a Senator, or President of the United States.

Harold Ickes, to keep the Forest Service autonomous from the newly formed Department of Conservation and Public Works. Best known today for his pioneering work in American forestry in the early 1900s, Pinchot was also an ambitious, courageous, and colorful governor. The "Great Forestor," however, never realized his ambition either to become a Senator, or President of the United States.

To learn more about Pinchot's impact on national conservation policy in the early 1900s click here.

here.

To learn more about Pinchot's second term as governor between 1931 and 1935 click here.

here.

Born to money, Pinchot attended private schools in New York City, graduated from Yale in 1889, and then studied forestry in France and Germany, in programs that emphasized the scientific study of resources and government regulation to ensure long-term conservation of vital natural resources. In 1896, President Grover Cleveland appointed Pinchot to the National Forest Commission and then to head the Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. Pinchot retained this post under the Republican Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, under whom he headed the new National Forest Service.

After leaving Washington, Pinchot entered Pennsylvania politics. The conservative Republican machine defeated his bid for the United States Senate in 1914 and 1920, when he lost to Boies Penrose. In 1922, the year after Penrose died, Pinchot won the governorship by allying with the Mellon interests of Pittsburgh and the Pennsylvania Association of Manufacturers president

Disguising his reform objectives, Pinchot ran on a platform calling for "economy and efficiency" and courted women voters with the help of his flamboyant wife, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, who joined him in putting up nearly all of the $118,000 his campaign cost. Once inaugurated, he

In the 1920s, the control of the Republican Party in Pennsylvania was split between the Mellon/Grundy faction and the Vare machine in Philadelphia. Bill Vare, a tough working-class scrapper who had begun his life as a trash collector, then followed in his brothers' footsteps as the

In January 1920, the manufacture and sale of alcohol became illegal when the Eighteenth Amendment became the law of the land. Pinchot was a strong Prohibitionist, but Philadelphia, under the Vare machine's leadership, so openly flaunted its disregard of the law that in 1924 President Calvin Coolidge loaned incoming Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick the services of Marine Corps Lieutenant Smedley Darlington Butler to clean up the city and enforce Prohibition.

After an initial flurry of highly publicized raids and prosecutions, Butler failed in his mission. Philadelphians and other Pennsylvanians liked their liquor, and the machine bosses liked the money it fed into their treasuries.

When the Pennsylvania legislature, which never voted for the measure, refused to provide funds to enforce the federal law, Pinchot obtained voluntary contributions from the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Pennsylvania's current liquor laws, with sales restricted to state stores, stem from his refusal in his second term to approve of private sales after Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

As governor, Pinchot pushed through as many reforms as the state legislature would permit. He instituted the Giant Power Survey Board to regulate the state's principal electric utilities, attempted to help Pennsylvania's miners during the national

He streamlined state government,

Forbidden from succeeding himself, Pinchot again ran for the United States Senate in 1926 but lost the Republican nomination to William Vare in a three-way primary that also included sitting Senator George Wharton Pepper. (It says much for the weakness of the Democratic Party at this time that despite this infighting, Democrat and former Secretary of Labor

Pinchot took revenge by refusing to certify Vare's election, as the governor was empowered to do,

In 1930, Pinchot was re-elected to a four-year term as governor by less than 50,000 votes out of over two million cast. To fight the Depression, Pinchot instituted massive road-paving projects, soon known as

Outraged at the refusal of the state legislature to support relief measures for millions of unemployed Pennsylvanians in dire need, Pinchot in 1932 broke with his party and supported Franklin Roosevelt for president. Pinchot hoped his independence, support of government welfare programs, labor, and road building might propel him to the presidency, but the Republicans would not consider a renegade from one of the few states to support them in 1932.

After his term as governor, Pinchot spent much of the late 1930s fighting against his former friend, Interior Secretary

To learn more about Pinchot's impact on national conservation policy in the early 1900s click

To learn more about Pinchot's second term as governor between 1931 and 1935 click