![header=[Marker Text] body=[Was born on this site in 1830. Governor of Pennsylvania, 1879-83; first to serve four years under the State Constitution of 1873. Advocated correctional institutions for care of youthful offenders. Died in 1892. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3B2-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0m7m4-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Henry M. Hoyt

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Luzerne

Marker Location:

U.S. 11 (714 Wyoming Ave.), Kingston

Dedication Date:

February 10, 1952

Behind the Marker

Henry Hoyt provides proof that not all machine politicians fit Pennsylvania Republican boss  Simon Cameron's supposed definition of an honest politician as "a man who once bought, stays bought." Upon realizing the extent of the corruption that had elevated him to the governorship in 1879, Hoyt, yet another farm boy whose pre-political career included a law practice and service in the Civil War, turned on his intended handlers. In 1883 he showed his independence and anger at the state Republican leadership by congratulating Robert Pattison, the Democrat who succeeded him as governor, for returning the government to the people.

Simon Cameron's supposed definition of an honest politician as "a man who once bought, stays bought." Upon realizing the extent of the corruption that had elevated him to the governorship in 1879, Hoyt, yet another farm boy whose pre-political career included a law practice and service in the Civil War, turned on his intended handlers. In 1883 he showed his independence and anger at the state Republican leadership by congratulating Robert Pattison, the Democrat who succeeded him as governor, for returning the government to the people.

Born in Kingston, Luzerne County, Hoyt attended the Wilkes-Barre Academy, Wyoming Seminary, Lafayette College, and finally Williams College in Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1849. He then taught school four years before becoming a lawyer in 1853. An early member of the Republican Party, in 1856 he campaigned actively for its presidential candidate, John C. Fremont.

Hoyt's local prominence and Republican credentials led Governor Andrew Curtin to appoint him colonel of the 52nd Pennsylvania volunteers after the Civil War broke out in 1861. After three years service, he was captured by Confederates in July 1864 while leading an attack on Fort Johnson, which protected Charleston, South Carolina. After an unsuccessful prison escape, during which he was tracked down by bloodhounds, Hoyt gained his freedom in a prisoner exchange. By the end of the war, he had won the rank of brigadier general.

Andrew Curtin to appoint him colonel of the 52nd Pennsylvania volunteers after the Civil War broke out in 1861. After three years service, he was captured by Confederates in July 1864 while leading an attack on Fort Johnson, which protected Charleston, South Carolina. After an unsuccessful prison escape, during which he was tracked down by bloodhounds, Hoyt gained his freedom in a prisoner exchange. By the end of the war, he had won the rank of brigadier general.

After the war, Hoyt, like Winfield Scott Hancock,

Winfield Scott Hancock,  James Beaver,

James Beaver,  John White Geary, and many other prominent Pennsylvania officers, became active in politics. Hoyt worked his way up from a revenue collector in Luzerne and Susquehanna counties to chairman of Pennsylvania's Republican Party in 1875. In the late 1870s, the scandals of the Grant administration and the violence that accompanied the nationwide

John White Geary, and many other prominent Pennsylvania officers, became active in politics. Hoyt worked his way up from a revenue collector in Luzerne and Susquehanna counties to chairman of Pennsylvania's Republican Party in 1875. In the late 1870s, the scandals of the Grant administration and the violence that accompanied the nationwide  railroad strike of 1877 - much of which occurred in Pennsylvania - turned voters against the Republican Party, which lost control of the Pennsylvania Assembly to the Democrats for the first time since the Civil War. A war hero with a record of political honesty, Hoyt was a logical man for the Republican state political bosses to run for governor in 1878.

railroad strike of 1877 - much of which occurred in Pennsylvania - turned voters against the Republican Party, which lost control of the Pennsylvania Assembly to the Democrats for the first time since the Civil War. A war hero with a record of political honesty, Hoyt was a logical man for the Republican state political bosses to run for governor in 1878.

In the 1870s, Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron was national boss of the Pennsylvania Republican Party. Within the state, however, Pennsylvania state secretary Matthew Quay had emerged as the state party leader and kingmaker through his control of the state's revenues. To win the election, Quay attempted to split the opposition vote by persuading the National-Greenback Party, which was devoted to reducing the nation's domination by wealthy businessmen, to run its own candidate for governor rather than to merge with the Democrats. Quay's gambit worked. Hoyt won by 22,000 votes out of the nearly 700,000 cast.

Matthew Quay had emerged as the state party leader and kingmaker through his control of the state's revenues. To win the election, Quay attempted to split the opposition vote by persuading the National-Greenback Party, which was devoted to reducing the nation's domination by wealthy businessmen, to run its own candidate for governor rather than to merge with the Democrats. Quay's gambit worked. Hoyt won by 22,000 votes out of the nearly 700,000 cast.

Hoyt's administration was soon rocked with scandals that caused him to break with the powers that had installed him in the state house. A pro-business Republican, he approved the state legislature's bill that paid the Pennsylvania Railroad $4 million in reparations for damages it suffered during the railroad strike of 1877. But he was outraged when the state attorney general pardoned three members of the Pennsylvania Assembly and five other men who had been convicted of accepting bribes to pass this law. Hoyt found an important ally in state treasurer Samuel Butler. Although Quay had arranged his appointment, Butler proved as independent as Hoyt, exposing Quay's speculation with government money.

Hoyt was a fairly able governor, who began his administration criticizing the nation's financial speculators for plunging the country into the Panic, or Depression, of 1873 He also proposed legislation to address some of the major issues of the day. Deeply concerned about the mistreatment of inmates in the state's prisons, he successfully pressed for modification of the state's policy of keeping all prisoners in solitary confinement, a policy Philadelphia's

Panic, or Depression, of 1873 He also proposed legislation to address some of the major issues of the day. Deeply concerned about the mistreatment of inmates in the state's prisons, he successfully pressed for modification of the state's policy of keeping all prisoners in solitary confinement, a policy Philadelphia's  Eastern State Penitentiary had first introduced in 1829 in the hope that isolation from the evil influences of others would result in a convict's rehabilitation. Unfortunately, it had too often resulted instead in extreme mental distress. Hoyt also authorized construction of a separate prison for first-time male offenders between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five, which provided schooling and instruction in a trade. The state also established a board to regulate the quality of medical schools and

Eastern State Penitentiary had first introduced in 1829 in the hope that isolation from the evil influences of others would result in a convict's rehabilitation. Unfortunately, it had too often resulted instead in extreme mental distress. Hoyt also authorized construction of a separate prison for first-time male offenders between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five, which provided schooling and instruction in a trade. The state also established a board to regulate the quality of medical schools and  banned school segregation during his term. And the governor made sure that his attorney general prosecuted railroads for giving preferred rates to preferred customers, at least where he could prove it.

banned school segregation during his term. And the governor made sure that his attorney general prosecuted railroads for giving preferred rates to preferred customers, at least where he could prove it.

Hoyt was not, however, totally independent of the machine. He may have had his reasons for pardoning four legislators who were convicted of accepting bribes to pass on the $4 million in damages the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) suffered in the great strike of 1877 to the state, but it did not seem that way to Democrats and reform Republicans, some of whom came from the oil-producing northwest corner of the state. They were angered because a tax on oil would provide the money. The scandal over the payback to the PRR split the party. In 1882, 40,000 of the faithful supported liberal Republican candidate John Stewart, almost exactly the margin by which Democrat Robert Pattison defeated machine candidate James Beaverto become the only Democratic governor of the state between the Civil War and the Great Depression.

James Beaverto become the only Democratic governor of the state between the Civil War and the Great Depression.

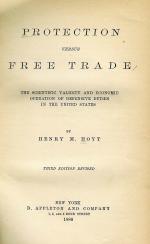

After leaving office in 1883, Hoyt returned to the practice of law in Wilkes-Barre and left politics behind him. He did, however, strongly defend Republican support of a high tariff on manufacturers in his 1885 book, Protection Versus Free Trade, arguing that it was essential to the nation's prosperity. Henry Hoyt died in Wilkes-Barre on December 1, 1892, and was buried in the Forty Fort Cemetery in Luzerne County. Today, Pennsylvanians can still honor him as a public official who refused to "stay bought."

Born in Kingston, Luzerne County, Hoyt attended the Wilkes-Barre Academy, Wyoming Seminary, Lafayette College, and finally Williams College in Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1849. He then taught school four years before becoming a lawyer in 1853. An early member of the Republican Party, in 1856 he campaigned actively for its presidential candidate, John C. Fremont.

Hoyt's local prominence and Republican credentials led Governor

After the war, Hoyt, like

In the 1870s, Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron was national boss of the Pennsylvania Republican Party. Within the state, however, Pennsylvania state secretary

Hoyt's administration was soon rocked with scandals that caused him to break with the powers that had installed him in the state house. A pro-business Republican, he approved the state legislature's bill that paid the Pennsylvania Railroad $4 million in reparations for damages it suffered during the railroad strike of 1877. But he was outraged when the state attorney general pardoned three members of the Pennsylvania Assembly and five other men who had been convicted of accepting bribes to pass this law. Hoyt found an important ally in state treasurer Samuel Butler. Although Quay had arranged his appointment, Butler proved as independent as Hoyt, exposing Quay's speculation with government money.

Hoyt was a fairly able governor, who began his administration criticizing the nation's financial speculators for plunging the country into the

Hoyt was not, however, totally independent of the machine. He may have had his reasons for pardoning four legislators who were convicted of accepting bribes to pass on the $4 million in damages the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) suffered in the great strike of 1877 to the state, but it did not seem that way to Democrats and reform Republicans, some of whom came from the oil-producing northwest corner of the state. They were angered because a tax on oil would provide the money. The scandal over the payback to the PRR split the party. In 1882, 40,000 of the faithful supported liberal Republican candidate John Stewart, almost exactly the margin by which Democrat Robert Pattison defeated machine candidate

After leaving office in 1883, Hoyt returned to the practice of law in Wilkes-Barre and left politics behind him. He did, however, strongly defend Republican support of a high tariff on manufacturers in his 1885 book, Protection Versus Free Trade, arguing that it was essential to the nation's prosperity. Henry Hoyt died in Wilkes-Barre on December 1, 1892, and was buried in the Forty Fort Cemetery in Luzerne County. Today, Pennsylvanians can still honor him as a public official who refused to "stay bought."