![header=[Marker Text] body=[Inventor of a telephone for which he sought a patent in 1880. Claims contested by Bell Telephone, which won the court decision in 1888. Born in this village, July 14, 1827, where he developed his inventions; he removed in 1904 to Camp Hill, where he died November 2, 1911. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-35C-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0l5n3-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Daniel Drawbaugh

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Cumberland

Marker Location:

155 Lake Rd. (SR 2033) at Eberly's Mill, 1 mile W of New Cumberland

Dedication Date:

May 1, 1965

Behind the Marker

The history of great inventions is rarely simple. Successful inventors build upon the work of countless predecessors. Their successes, reputations, and claims also depend upon their business skills or the business associates who finance and protect them against aggressive competitors. The more valuable the invention, the greater was the scramble for its credit and rewards. Such was the case with the telephone.

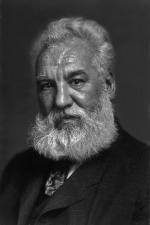

In the 1860s and 1870s, a number of men were experimenting with the transmission of the human voices over electrical wires, including Tuft's University Professor Amos Dolbear, Thomas Edison, and Chicago-based inventor Elisha Gray. Others also staked their claim for invention of what would become the telephone, including Daniel Drawbaugh of Eberly Mills, Pa.

Alexander Graham Bell was the first to file a patent on the key components of the telephone. Between 1876, when he did so, and 1894, his patents were challenged in 600 separate cases, the records for which filled 149 volumes. In 1878, the same year that Bell's business partners organized a national company, the powerful Western Union Company entered the telephone race with patents and claimed it had acquired these from Edison, Gray, Dolbear, and others. Western Union settled in 1879, but Bell was so distressed the by endless barrage of lawsuits that he wrote his wife, "I am afraid to make more inventions ...."

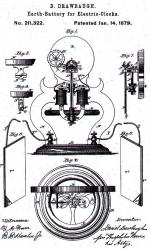

The Bell Company continued to file lawsuits against endless infringers, who set up companies to sell as much stock as possible before the courts shut them down. Bell won every case, most with little fanfare until 1880, when Bell sued the newly formed People's Telephone Company for starting a telephone business in New York. People's entered the telephone industry with unpatented claims it had purchased from Daniel Drawbaugh, a practical machinist and inventor in rural Cumberland County, Pa., whose chief claim to fame were his patents on a mechanical coin sorter and magnetic clock.

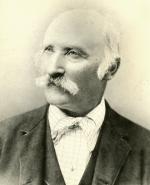

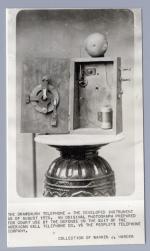

Early in 1880, Drawbaugh announced that in 1866 or 1867 he had invented the Bell telephone, Edison transmitter, and successful telephone components, but had failed to apply for a patent for want of funds. Drawbaugh's claims had enough credence for People's to mount a strong legal defense. To support Drawbaugh's claim, People's Telephone brought 300 to 400 witnesses who testified in his defense and recorded some 1,200 pages of testimony. Drawbaugh emerged from witnesses as the classic American inventor.

The son and grandson of blacksmiths, Drawbaugh, so the story went, early on demonstrated a fascination with invention so all consuming that a schoolteacher flogged him for working on a model windmill during class time. He then made his living as a mechanic, working in a shop in the back of the unused Clover Mill, which sat on a shaded peninsula between the Yellow Breeches Creek and the Cedar Run in the tiny village of Eberlys Mills, Cumberland County. Sympathetic witnesses testified that jacks of all trades "a good many [of whom] cobbled around a little sometimes," routinely gathered at Drawbaugh's shop on Saturday nights for games of "seven-up" and turkey shoots on the lawn. And there Drawbaugh mended clocks, repaired tools, and devised all manner of inventions.

Neighbors testified that in 1866 or 1867 they had heard the muffled transmission of words from the floor above, through an instrument that Drawbaugh now insisted included a "flexible membrane" over a teacup that he had connected by a piece of wire to a receiver powered by an electro-magnet. They said that no one had encouraged the inveterate tinkerer to protect his invention, and that his family had continually prodded Drawbaugh to stop wasting his time.

His brother stated that upon hearing of Drawbaugh's "talking machine," he had accused him "quite severely of wasting time on foolish inventions. I told him that they would amount to nothing, and that he had a large family, and that he should turn his attention to something that would support his family better than by working at these foolish things, and that it would amount to nothing in the end." Forced to take boarders into the family home to pay the bills, his wife hounded him about his activities, and was said to have smashed his photographic equipment "in order to stop Daniel from fooling around with them."

Bell's lawyers painted a quite different picture, insisting that Drawbaugh was a charlatan with no demonstrable proof for his claims. They demonstrated that the each of his alleged telephone inventions were identical with types known in 1880; provided evidence that he was financially well off in the 1860s, owning his home and stocking his shop with a variety of machine tools; and argued that he had failed to file his patent in a timely fashion. Drawbaugh did little to help his own case when under oath he admitted to having heard about Bell's exhibit while attending Philadelphia's Centennial Exposition in 1876, but had made no mention to anyone about his own similar invention a few years earlier.

The Drawbaugh case dragged on for seven years, until the Supreme Court finally ruled 4-3 against Drawbaugh's claim, after which Drawbaugh accused a justice of a conflict of interest for holding significant stock in Bell Telephone. People's Telephone Company soon went out of business. Unfazed, Drawbaugh continued his claims against Bell. In 1903, he returned briefly to the national stage when he publicly insisted that he had invented radio before Marconi. Drawbaugh died of a heart attack in 1911, soon after Bell Telephone Company offered him a settlement to end his litigation once and for all.

Drawbaugh was not alone in his belief that he, as much as Bell, should have received the credit and rewards for invention the telephone. Gray and Dolbear continued to believe that they had been robbed of both the credit and money that they deserved for their roles in the development of the telephone. Similar controversies surround the invention and development of other technologies, including, for example, Sephaniah Reese's role in the development of the gas-powered automobile.

Sephaniah Reese's role in the development of the gas-powered automobile.

In the 1860s and 1870s, a number of men were experimenting with the transmission of the human voices over electrical wires, including Tuft's University Professor Amos Dolbear, Thomas Edison, and Chicago-based inventor Elisha Gray. Others also staked their claim for invention of what would become the telephone, including Daniel Drawbaugh of Eberly Mills, Pa.

Alexander Graham Bell was the first to file a patent on the key components of the telephone. Between 1876, when he did so, and 1894, his patents were challenged in 600 separate cases, the records for which filled 149 volumes. In 1878, the same year that Bell's business partners organized a national company, the powerful Western Union Company entered the telephone race with patents and claimed it had acquired these from Edison, Gray, Dolbear, and others. Western Union settled in 1879, but Bell was so distressed the by endless barrage of lawsuits that he wrote his wife, "I am afraid to make more inventions ...."

The Bell Company continued to file lawsuits against endless infringers, who set up companies to sell as much stock as possible before the courts shut them down. Bell won every case, most with little fanfare until 1880, when Bell sued the newly formed People's Telephone Company for starting a telephone business in New York. People's entered the telephone industry with unpatented claims it had purchased from Daniel Drawbaugh, a practical machinist and inventor in rural Cumberland County, Pa., whose chief claim to fame were his patents on a mechanical coin sorter and magnetic clock.

Early in 1880, Drawbaugh announced that in 1866 or 1867 he had invented the Bell telephone, Edison transmitter, and successful telephone components, but had failed to apply for a patent for want of funds. Drawbaugh's claims had enough credence for People's to mount a strong legal defense. To support Drawbaugh's claim, People's Telephone brought 300 to 400 witnesses who testified in his defense and recorded some 1,200 pages of testimony. Drawbaugh emerged from witnesses as the classic American inventor.

The son and grandson of blacksmiths, Drawbaugh, so the story went, early on demonstrated a fascination with invention so all consuming that a schoolteacher flogged him for working on a model windmill during class time. He then made his living as a mechanic, working in a shop in the back of the unused Clover Mill, which sat on a shaded peninsula between the Yellow Breeches Creek and the Cedar Run in the tiny village of Eberlys Mills, Cumberland County. Sympathetic witnesses testified that jacks of all trades "a good many [of whom] cobbled around a little sometimes," routinely gathered at Drawbaugh's shop on Saturday nights for games of "seven-up" and turkey shoots on the lawn. And there Drawbaugh mended clocks, repaired tools, and devised all manner of inventions.

Neighbors testified that in 1866 or 1867 they had heard the muffled transmission of words from the floor above, through an instrument that Drawbaugh now insisted included a "flexible membrane" over a teacup that he had connected by a piece of wire to a receiver powered by an electro-magnet. They said that no one had encouraged the inveterate tinkerer to protect his invention, and that his family had continually prodded Drawbaugh to stop wasting his time.

His brother stated that upon hearing of Drawbaugh's "talking machine," he had accused him "quite severely of wasting time on foolish inventions. I told him that they would amount to nothing, and that he had a large family, and that he should turn his attention to something that would support his family better than by working at these foolish things, and that it would amount to nothing in the end." Forced to take boarders into the family home to pay the bills, his wife hounded him about his activities, and was said to have smashed his photographic equipment "in order to stop Daniel from fooling around with them."

Bell's lawyers painted a quite different picture, insisting that Drawbaugh was a charlatan with no demonstrable proof for his claims. They demonstrated that the each of his alleged telephone inventions were identical with types known in 1880; provided evidence that he was financially well off in the 1860s, owning his home and stocking his shop with a variety of machine tools; and argued that he had failed to file his patent in a timely fashion. Drawbaugh did little to help his own case when under oath he admitted to having heard about Bell's exhibit while attending Philadelphia's Centennial Exposition in 1876, but had made no mention to anyone about his own similar invention a few years earlier.

The Drawbaugh case dragged on for seven years, until the Supreme Court finally ruled 4-3 against Drawbaugh's claim, after which Drawbaugh accused a justice of a conflict of interest for holding significant stock in Bell Telephone. People's Telephone Company soon went out of business. Unfazed, Drawbaugh continued his claims against Bell. In 1903, he returned briefly to the national stage when he publicly insisted that he had invented radio before Marconi. Drawbaugh died of a heart attack in 1911, soon after Bell Telephone Company offered him a settlement to end his litigation once and for all.

Drawbaugh was not alone in his belief that he, as much as Bell, should have received the credit and rewards for invention the telephone. Gray and Dolbear continued to believe that they had been robbed of both the credit and money that they deserved for their roles in the development of the telephone. Similar controversies surround the invention and development of other technologies, including, for example,

Beyond the Marker