![header=[Marker Text] body=[Legendary football player, nicknamed "The Galloping Ghost," born in Forksville. Member, College Football Hall of Fame. Career began at Wheaton (Ill.) High School; scored 75 touchdowns. Played 1923-25 for the University of Illinois; an All - American each year. Professional player, 1925-34, mainly with the Chicago Bears. Lived in Forksville to age five; his family had farmed and worked in lumber camps nearby. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-30E-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k6e6-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Harold Red Grange

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Sullivan

Marker Location:

154 off of Rte 87, Forksville

Dedication Date:

August 25, 1999

Behind the Marker

In an era of colorful sports nicknames, Harold Grange was such a gridiron nonpareil that it took two to encompass his essence: "Red" to capture his distinctive shock of wavy hair and "The Galloping Ghost" to evince the mythic qualities of his elusive running style. In what is still considered the most remarkable display of open-field dazzle in the game's history, Grange led his Fighting Illini, on the day in 1924 that their new stadium was dedicated, to an upset of the University of Michigan, undefeated since 1921, by scoring four touchdowns in the game's first twelve minutes. After returning the opening kickoff the length of the field, the unstoppable halfback added runs of 67, 55, and 44 yards on Illinois" next three possessions. By the time the final gun sounded, he had zigged for another touchdown, zagged for a total of 402 yards on just twenty-one carries, and completed six passes, one for a score.

To the eternal chagrin of the Penn State Alumni Association, the Granges left Pennsylvania in 1908 for Wheaton, Illinois, shortly after the future Hall of Famer's mother died. Harold Edward "Red" Grange was born five years earlier in Forksville, west of Wilkes-Barre, south of the New York border, where his father was a foreman in one of the area's many lumber camps. Growing up in Wheaton, the boy was diagnosed with a heart murmur, which didn't stop him from earning sixteen varsity letters in four sports in high school. To build strength and endurance, Grange delivered heavy blocks of ice from door to door in the summer, a job that kept him fit through college, as well.

At the University of Illinois, Grange showed no stomach–at first–for football. Knocked unconscious on the field once in high school, he thought he was too small for the college game. Once some fraternity brothers pushed him to try out for the freshman squad, however, he showed brilliance. If only collegiate rules then had allowed him to play for the varsity; Illinois" 1922 team was a dismal 2-5. Led by Grange the following year–he scored an auspicious three touchdowns in his varsity debut– the Illini went undefeated on their way to being named co-national champions, and Grange earned the first of his three All-America designations. More enduringly, his exploits changed the way Americans thought about college football. Home from a World War feeling safe and prosperous again, the nation reveled in its outsized sporting heroes: slugger Babe Ruth, heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, golfer Bobby Jones, and the racehorse Man o" War. Now college football had a bonafide superstar, too.

His derring-do elicited streams of purple prose from the press box, his legend growing with each report sent coast to coast by wire services that brought the most distant news to every front stoop in the country. After the Michigan game in 1924, writer Grantland Rice, never one to err on the side of modesty, coined the spectrally evocative nickname, and went on to describe Grange poetically as:

Showing just a bit more restraint, Damon Runyon, the reigning sportswriter of the day, likened him "three or four men and a horse rolled into one."

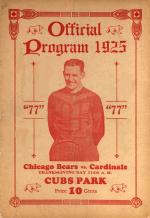

In 1925, after suffering three losses in the first four games, Grange took control of the team at quarterback, Illinois righted itself, and Grange became the first college football player featured on the cover of Time. Two days after his final college game, Grange did the unthinkable: He turned pro.

Although the first professional football game had been played thirty-three years before, the new National Football League was still in its infancy. Compared to the nobility of its collegiate cousin–second only to baseball in its place in the American heart–professional football was deemed unpure, unsporting, and unseemly, nothing more than a refuge for brawny ruffians. Grange would change that image, but not without another razzle-dazzle effort.

first professional football game had been played thirty-three years before, the new National Football League was still in its infancy. Compared to the nobility of its collegiate cousin–second only to baseball in its place in the American heart–professional football was deemed unpure, unsporting, and unseemly, nothing more than a refuge for brawny ruffians. Grange would change that image, but not without another razzle-dazzle effort.

His decision to go pro was so frowned on by his college coach, college football in general, and the mass of the sporting press who so adored him - they all fervently subscribed to the ideal of the scholar-athlete for whom money was inconsequential and school spirit all- that Grange later admitted, "I think I might have been more popular if I joined the Capone bunch." And there was a further smudge on the ideal: Grange had engaged an agent–unheard of at the time–to make his deal: $100,000 and a percentage of gate receipts for one barnstorming seventeen-game season played in venues from New York to Los Angeles in just over two months. Not even Babe Ruth could command such a bankroll yet; the next-highest salary in the teetering National Football League was just $500 a game.

Grange earned his money. With the unrivalled marquee value of his name, he put fans in the seats wherever he played–65,000 in New York alone to help save the Giants from imminent collapse–and another 75,000 in Los Angeles. In those whirlwind two months, Grange raised the credibility of professional football and fan interest in the sport enough to secure its immediate future. "We made enough pro football converts all over the land to give the sport the shot in the arm it so badly needed," he said years later, "and, from the 1925 season on, professional football began to grow steadily in popularity."

Continuing to play through 1935, Grange never matched the brilliance of his college feats. Still, his personality, his reputation, and his agent all came together to fashion Grange into the paradigm of the modern professional athlete. His name and his face carried the cachet that marketers swoon over, and his bevy of commercial endorsements extended from dolls and candy bars to shoes and meatloaf.

After retiring, Grange coached for several seasons, sold insurance, and, blazed one final sporting trail by becoming biggest of the early star athletes to emerge as a successful commentator, first on radio, then on television. A charter member of both the college and professional football Halls of Fame, Red Grange was the only unanimous selection to college football's 100th Anniversary All-America squad. He died in 1991.

To the eternal chagrin of the Penn State Alumni Association, the Granges left Pennsylvania in 1908 for Wheaton, Illinois, shortly after the future Hall of Famer's mother died. Harold Edward "Red" Grange was born five years earlier in Forksville, west of Wilkes-Barre, south of the New York border, where his father was a foreman in one of the area's many lumber camps. Growing up in Wheaton, the boy was diagnosed with a heart murmur, which didn't stop him from earning sixteen varsity letters in four sports in high school. To build strength and endurance, Grange delivered heavy blocks of ice from door to door in the summer, a job that kept him fit through college, as well.

At the University of Illinois, Grange showed no stomach–at first–for football. Knocked unconscious on the field once in high school, he thought he was too small for the college game. Once some fraternity brothers pushed him to try out for the freshman squad, however, he showed brilliance. If only collegiate rules then had allowed him to play for the varsity; Illinois" 1922 team was a dismal 2-5. Led by Grange the following year–he scored an auspicious three touchdowns in his varsity debut– the Illini went undefeated on their way to being named co-national champions, and Grange earned the first of his three All-America designations. More enduringly, his exploits changed the way Americans thought about college football. Home from a World War feeling safe and prosperous again, the nation reveled in its outsized sporting heroes: slugger Babe Ruth, heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, golfer Bobby Jones, and the racehorse Man o" War. Now college football had a bonafide superstar, too.

His derring-do elicited streams of purple prose from the press box, his legend growing with each report sent coast to coast by wire services that brought the most distant news to every front stoop in the country. After the Michigan game in 1924, writer Grantland Rice, never one to err on the side of modesty, coined the spectrally evocative nickname, and went on to describe Grange poetically as:

"A streak of fire. A breath of flame

Eluding all who reach and clutch;

A gray ghost thrown into the game

That rival hands may never touch."

Showing just a bit more restraint, Damon Runyon, the reigning sportswriter of the day, likened him "three or four men and a horse rolled into one."

In 1925, after suffering three losses in the first four games, Grange took control of the team at quarterback, Illinois righted itself, and Grange became the first college football player featured on the cover of Time. Two days after his final college game, Grange did the unthinkable: He turned pro.

Although the

His decision to go pro was so frowned on by his college coach, college football in general, and the mass of the sporting press who so adored him - they all fervently subscribed to the ideal of the scholar-athlete for whom money was inconsequential and school spirit all- that Grange later admitted, "I think I might have been more popular if I joined the Capone bunch." And there was a further smudge on the ideal: Grange had engaged an agent–unheard of at the time–to make his deal: $100,000 and a percentage of gate receipts for one barnstorming seventeen-game season played in venues from New York to Los Angeles in just over two months. Not even Babe Ruth could command such a bankroll yet; the next-highest salary in the teetering National Football League was just $500 a game.

Grange earned his money. With the unrivalled marquee value of his name, he put fans in the seats wherever he played–65,000 in New York alone to help save the Giants from imminent collapse–and another 75,000 in Los Angeles. In those whirlwind two months, Grange raised the credibility of professional football and fan interest in the sport enough to secure its immediate future. "We made enough pro football converts all over the land to give the sport the shot in the arm it so badly needed," he said years later, "and, from the 1925 season on, professional football began to grow steadily in popularity."

Continuing to play through 1935, Grange never matched the brilliance of his college feats. Still, his personality, his reputation, and his agent all came together to fashion Grange into the paradigm of the modern professional athlete. His name and his face carried the cachet that marketers swoon over, and his bevy of commercial endorsements extended from dolls and candy bars to shoes and meatloaf.

After retiring, Grange coached for several seasons, sold insurance, and, blazed one final sporting trail by becoming biggest of the early star athletes to emerge as a successful commentator, first on radio, then on television. A charter member of both the college and professional football Halls of Fame, Red Grange was the only unanimous selection to college football's 100th Anniversary All-America squad. He died in 1991.