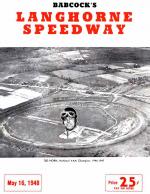

![header=[Marker Text] body=[Opened in 1926, this circular one-mile dirt track was known as the "Big Left Turn." It hosted a NASCAR inaugural race in 1949. Notable drivers Doc Mackenzie, Joie Chitwood, Rex Mays, Lee Petty, Dutch Hoag, A.J. Foyt, and Mario Andretti raced here in stock, midget, sprint, and Indy cars. Langhorne was reshaped as a "D" and paved in 1965. The National Open Champion-ship run here was regarded as the "Indy of the East." Final race was held in 1971. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-307-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k6a8-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Langhorne Speedway

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Bucks

Marker Location:

1939 E Lincoln Hwy., Langhorne

Dedication Date:

October 14, 2006

Behind the Marker

NASCAR legend Richard Petty had no doubt about the moment people began racing each other in automobiles. "It was," said Petty, "the day they built the second automobile." At first, intrepid horseless carriage drivers raced from one point to another, but in the 1890s state fairs began to stage auto races on their dirt oval horse tracks, where people could watch a race from start to finish.

In July of 1899 the Belmont Driving Park, near Narberth, became the first Pennsylvania horse race track to stage an automobile race. In 1900, Point Breeze Racetrack, located on the southeast side of Penrose Avenue opposite the end of S. 26th St in South Philadelphia, started its own auto competition. Six years later, Point Breeze was the site of the first racecar fatality in Pennsylvania, for here professional driver Ernest Keeler died when he rolled his car during a practice run on November 23, 1906. Two years later, sanctioned road races began in Philadelphia on a course that wound through Fairmount Park.

In the years that followed, auto racing spread to horse-racing tracks throughout the Commonwealth, for the speed and danger of men racing machines through mud, dirt, and dust proved immensely popular and extremely profitable. It was not until 1926, however, that the directors of the National Motor Racing Association decided to build the nation's first dirt race track designed specifically for auto racing.

Near Langhorne in Bucks County, PA, they carved out a one-mile track, designed as round as possible to fit onto their eighty-nine-acre plot of swampland. Early practice sessions proved their "New Philadelphia Speedway" to be the fastest dirt track in the world. After Toni Dawson completed a practice lap at 94 miles-per-hour, shattering Ralph DePalma's world speed record by 7 mph, the organizers required qualifiers average more than 90 mph to reduce the first race's huge field of 100 entries. On June 12, 1926, a huge crowd turned out to watch Langhorne's inaugural 50-lap contest of twenty-four very fast racers, which was won by twenty-one-year-old Philadelphian Fred Winnai (1905-1977).

With cars in a constant four-wheel drift or running sideways in great dirt-throwing powerslides, Langhorne treated the spectators to some of the closest, most fiercely contested events in the history of American auto racing. Unfortunately, the close competition also caused some terrible accidents. On August 7, 1926, former prizefighter Lou Fink became the track's first fatality when his car crashed near the main stands. That October, Russ Snowberger drove a Miller-powered racer to victory while dodging rocks, holes, and crashes in Langhorne's first 100-mile contest. "The dust was so bad," Snowberger exclaimed, "I couldn't see more than ten or twelve yards ahead." And it only got worse. Its underground springs and shifting subsoil made Langhorne a treacherous course. Racing cars quickly rutted the surface and dug up huge holes, and the dust was so bad that fans stopped coming in 1928 because they could not see the action.

The track was in danger of closing when racing promoter Ralph "Pappy" Hankinson took Langhorne over. Pappy dug up the track and treated the soil with 30,000 gallons of used motor oil, which cut down the dust, held the soft spots in the track together, and soon turned Langhorne into the "Indianapolis of the East." On May 3, 1930, Hankinson carded a 100-mile race, which featured a tremendous duel between Winnai, Deacon Litz, and future Indy champs Wilbur Shaw and "Wild Bill" Cummings. This battle royal went to Cummings. "That was the toughest race I ever drove," the exhausted Cummings told Hankinson. "Don't ever run another 100-miler here. Long races at this place are too tiring to be safe."

What made Langhorne so tiring was the absence of straightaways. To navigate "the big left turn," drivers had to grip the wheel without rest in a death-grip left-turn that lasted 100 miles. Auto-racing historian Joe Scalzo recalls an additional danger, explaining that "as a cut-rate way of taming the dust storms, management routinely had contractors pump vast reservoirs of used motor oil and crankcase sludge onto the track. Essentially, drivers were putting their cars and lives at risk upon a slick witches" brew of toxic sludge."

But the races continued. One hundred-mile races for Indianapolis-type racers, also known as championship cars, were the great dirt track tests of man and machine. When Hankinson staged the events at Langhorne, crowds in excess of 40,000 were not uncommon. Many drivers feared the Langhorne track, which continued to exact a heavy toll of injuries and fatalities, but others were more than willing to try their mettle against the unforgiving mile of earth. Popular sprint cars, midgets, motorcycles, modified sportsman, and much later, the NASCAR stock cars, also raced at "The Big Left Turn."

Langhorne closed after American entrance into World War II, then reopened under new owner John Babcock, who staged the first post-war race on June 30, 1946. In the 1950s, Babcock sold the track to racing promoters Irv Fried and Al Gerber, under whose direction Langhorne achieved its greatest popularity. From 1956 to 1970, the United States Auto Club sanctioned open-wheel races at Langhorne won by such famous names as A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Bobby Unser, and Gordon Johncock. Serious injuries and fatalities continued, so in 1965 Fried and Gerber reshaped and paved the track into a "D" configuration. Although dirt-track purists and many of the drivers felt the racing was less exciting, faster speeds and close competition kept fans coming and ended driver fatalities. On October 10, 1971, Fried and Gerber staged the last race at Langhorne, a 200-mile "National Open" for modified stock cars won by Roger Treichler. A few days later a developer began to bulldoze the world's most famous one-mile speedway to make way for a shopping center.

Auto racing, however, continued to thrive in Pennsylvania. In the later half of the twentieth century, Pennsylvania enjoyed international exposure through the Nazareth Speedway and Pocono Raceway. Built near a 5/8-mile dirt track that had opened in the Lehigh Valley in 1910, Nazareth Speedway hosted NASCAR, Indy Racing League, and Champ Car World Series (CART) sanctioned events from 1987 until it closed in 2004. The Speedway also became known for its association with racing champions Mario and Michael Andretti, who continue to live nearby. Opened in 1969 as a 2 1/2-mile triangle, the Pocono Raceway held an annual 500-mile CART Indy-style series race from 1971 to 1989, and continues to host annual NASCAR races in June and August. While the number of racetracks in operation varies from year to year, Pennsylvania in 1994 had fifty-three active oval tracks, eight active drag strips, and nine road courses, one of which was active. In 2007, on any given spring, summer or fall weekend, the roar of nearly fifty short tracks comes alive across the Commonwealth.

In July of 1899 the Belmont Driving Park, near Narberth, became the first Pennsylvania horse race track to stage an automobile race. In 1900, Point Breeze Racetrack, located on the southeast side of Penrose Avenue opposite the end of S. 26th St in South Philadelphia, started its own auto competition. Six years later, Point Breeze was the site of the first racecar fatality in Pennsylvania, for here professional driver Ernest Keeler died when he rolled his car during a practice run on November 23, 1906. Two years later, sanctioned road races began in Philadelphia on a course that wound through Fairmount Park.

In the years that followed, auto racing spread to horse-racing tracks throughout the Commonwealth, for the speed and danger of men racing machines through mud, dirt, and dust proved immensely popular and extremely profitable. It was not until 1926, however, that the directors of the National Motor Racing Association decided to build the nation's first dirt race track designed specifically for auto racing.

Near Langhorne in Bucks County, PA, they carved out a one-mile track, designed as round as possible to fit onto their eighty-nine-acre plot of swampland. Early practice sessions proved their "New Philadelphia Speedway" to be the fastest dirt track in the world. After Toni Dawson completed a practice lap at 94 miles-per-hour, shattering Ralph DePalma's world speed record by 7 mph, the organizers required qualifiers average more than 90 mph to reduce the first race's huge field of 100 entries. On June 12, 1926, a huge crowd turned out to watch Langhorne's inaugural 50-lap contest of twenty-four very fast racers, which was won by twenty-one-year-old Philadelphian Fred Winnai (1905-1977).

With cars in a constant four-wheel drift or running sideways in great dirt-throwing powerslides, Langhorne treated the spectators to some of the closest, most fiercely contested events in the history of American auto racing. Unfortunately, the close competition also caused some terrible accidents. On August 7, 1926, former prizefighter Lou Fink became the track's first fatality when his car crashed near the main stands. That October, Russ Snowberger drove a Miller-powered racer to victory while dodging rocks, holes, and crashes in Langhorne's first 100-mile contest. "The dust was so bad," Snowberger exclaimed, "I couldn't see more than ten or twelve yards ahead." And it only got worse. Its underground springs and shifting subsoil made Langhorne a treacherous course. Racing cars quickly rutted the surface and dug up huge holes, and the dust was so bad that fans stopped coming in 1928 because they could not see the action.

The track was in danger of closing when racing promoter Ralph "Pappy" Hankinson took Langhorne over. Pappy dug up the track and treated the soil with 30,000 gallons of used motor oil, which cut down the dust, held the soft spots in the track together, and soon turned Langhorne into the "Indianapolis of the East." On May 3, 1930, Hankinson carded a 100-mile race, which featured a tremendous duel between Winnai, Deacon Litz, and future Indy champs Wilbur Shaw and "Wild Bill" Cummings. This battle royal went to Cummings. "That was the toughest race I ever drove," the exhausted Cummings told Hankinson. "Don't ever run another 100-miler here. Long races at this place are too tiring to be safe."

What made Langhorne so tiring was the absence of straightaways. To navigate "the big left turn," drivers had to grip the wheel without rest in a death-grip left-turn that lasted 100 miles. Auto-racing historian Joe Scalzo recalls an additional danger, explaining that "as a cut-rate way of taming the dust storms, management routinely had contractors pump vast reservoirs of used motor oil and crankcase sludge onto the track. Essentially, drivers were putting their cars and lives at risk upon a slick witches" brew of toxic sludge."

But the races continued. One hundred-mile races for Indianapolis-type racers, also known as championship cars, were the great dirt track tests of man and machine. When Hankinson staged the events at Langhorne, crowds in excess of 40,000 were not uncommon. Many drivers feared the Langhorne track, which continued to exact a heavy toll of injuries and fatalities, but others were more than willing to try their mettle against the unforgiving mile of earth. Popular sprint cars, midgets, motorcycles, modified sportsman, and much later, the NASCAR stock cars, also raced at "The Big Left Turn."

Langhorne closed after American entrance into World War II, then reopened under new owner John Babcock, who staged the first post-war race on June 30, 1946. In the 1950s, Babcock sold the track to racing promoters Irv Fried and Al Gerber, under whose direction Langhorne achieved its greatest popularity. From 1956 to 1970, the United States Auto Club sanctioned open-wheel races at Langhorne won by such famous names as A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Bobby Unser, and Gordon Johncock. Serious injuries and fatalities continued, so in 1965 Fried and Gerber reshaped and paved the track into a "D" configuration. Although dirt-track purists and many of the drivers felt the racing was less exciting, faster speeds and close competition kept fans coming and ended driver fatalities. On October 10, 1971, Fried and Gerber staged the last race at Langhorne, a 200-mile "National Open" for modified stock cars won by Roger Treichler. A few days later a developer began to bulldoze the world's most famous one-mile speedway to make way for a shopping center.

Auto racing, however, continued to thrive in Pennsylvania. In the later half of the twentieth century, Pennsylvania enjoyed international exposure through the Nazareth Speedway and Pocono Raceway. Built near a 5/8-mile dirt track that had opened in the Lehigh Valley in 1910, Nazareth Speedway hosted NASCAR, Indy Racing League, and Champ Car World Series (CART) sanctioned events from 1987 until it closed in 2004. The Speedway also became known for its association with racing champions Mario and Michael Andretti, who continue to live nearby. Opened in 1969 as a 2 1/2-mile triangle, the Pocono Raceway held an annual 500-mile CART Indy-style series race from 1971 to 1989, and continues to host annual NASCAR races in June and August. While the number of racetracks in operation varies from year to year, Pennsylvania in 1994 had fifty-three active oval tracks, eight active drag strips, and nine road courses, one of which was active. In 2007, on any given spring, summer or fall weekend, the roar of nearly fifty short tracks comes alive across the Commonwealth.