![header=[Marker Text] body=[Erected 1749; once owned by Baron Stiegel. Operated by ironmaster George Ege, 1774-1824. Hessians were employed in Revolutionary days to cut a rock channel for water supply. Site is to the north of Womelsdorf.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-2A2-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k1s0-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Charming Forge

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Berks

Marker Location:

U.S. 422, Womelsdorf

Dedication Date:

April 30, 1947

Behind the Marker

Arthur Bining, Pennsylvania Iron Manufacturing in the 18th Century, 1973.

Located on Tulpehocken Creek in Berks County, Charming Forge exemplified two steps in American iron production in the 1700s and early 1800s. First, it was a refinery forge that processed iron from charcoal furnaces, which were primary iron producers, and like other refinery forges made wrought iron that blacksmiths and others could shape into various products. Second, Charming Forge had a slitting mill that turned wrought iron into slits that could be made into nails.

Michael Miller and John George Nikoll, a hammersmith who worked with iron, built Charming Forge about 1749 on Tulpehocken Creek and called it Tulpehocken Eisenhammer. In 1763 Henry William Stiegel bought a half interest in the forge and renamed it Charming Forge after the charming natural beauty of the locale, and built a fairly large forge capable of producing 300 tons of iron annually. Sometime around 1780, George Ege, the next owner, added a slitting mill to the operation. Ege also used Hessian soldiers captured during the American Revolution to construct the rock channel that supplied water power to the slitting mill.

Henry William Stiegel bought a half interest in the forge and renamed it Charming Forge after the charming natural beauty of the locale, and built a fairly large forge capable of producing 300 tons of iron annually. Sometime around 1780, George Ege, the next owner, added a slitting mill to the operation. Ege also used Hessian soldiers captured during the American Revolution to construct the rock channel that supplied water power to the slitting mill.

Colebrookdale Furnace and other Pennsylvania charcoal furnaces produced iron that was brittle and unmalleable. It was refinery forges, then, that created the stronger and more malleable “wrought” iron, by reheating and hammering the iron to drive off more of the carbon and impurities. The wrought iron could then be cast into stove plates and other products or used by blacksmiths, coopers, wheelwrights, and others, who could reheat, bend, and shape it into a wide variety of products.

Colebrookdale Furnace and other Pennsylvania charcoal furnaces produced iron that was brittle and unmalleable. It was refinery forges, then, that created the stronger and more malleable “wrought” iron, by reheating and hammering the iron to drive off more of the carbon and impurities. The wrought iron could then be cast into stove plates and other products or used by blacksmiths, coopers, wheelwrights, and others, who could reheat, bend, and shape it into a wide variety of products.

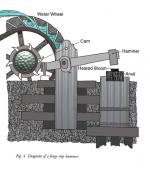

Refinery forges usually had two types of charcoal-heated hearths: a finery or refinery hearth and a chafery hearth. Workers heated rough bars of pig iron in a finery hearth until the iron became semi-molten. A skilled worker known as a finer then worked the semi-molten bars into a lump or half-bloom. Workers then used large hooks and wide-jawed tongs to place the glowing half-bloom on an anvil and pound it with a large water-powered forge hammer, a massive piece of iron mounted on an oak beam that connected to a water wheel.

Workers repeatedly reheated and pounded half-blooms until they produced flat, thick bars of wrought iron called anconies. The anconies not sold by the ironmasters were then reheated in a chafery hearth and hammered on an anvil to produce long bars of iron in different thicknesses. Forge workers then fashioned and cut the bars into shapes that blacksmiths and others could use. Workers also hammered out sheet and plate iron at some forges through the early 1800s.

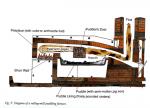

The slitting mill at Charming Forge processed wrought iron bars from the refinery forge. Here, workers used heavy, water-powered shears to cut the bars into strips, then heated the strips and passed them through rollers that reduced the strips to a desired thickness. Next they reheated the strips and passed them through grooved rollers that cut the strips into slits.

Slit iron often went to naileries, which put points on one end of the iron slits and heads on the other end to produce nails. Ironmasters located earlier slitting mills in rural areas near refinery forges, their sources of wrought iron, but they placed later slitting mills nearer towns and cities, which were their principal markets.

In the early nineteenth century, Pennsylvania ironmasters like Isaac Meason began to bypass forges altogether by combining puddling furnaces with rolls in new rolling mills, which reheated the iron and passing it back and forth through series of rollers to shape it into plate, sheet, bar and other iron products.

Isaac Meason began to bypass forges altogether by combining puddling furnaces with rolls in new rolling mills, which reheated the iron and passing it back and forth through series of rollers to shape it into plate, sheet, bar and other iron products.

By 1850 the iron industry had turned from forges to rolling mills, which produced wrought iron products and railroad rails cheaper, faster, and more efficiently. Charming Forge remained in operated until 1887, well after rolling mills has driven other refinery forges out of business.

"The dull, unvaried turning of the water wheel, the irregular splash of falling water, the rhythmic thump of the hammer, and the droning sound of the anvil were a part of life on the plantation."

Arthur Bining, Pennsylvania Iron Manufacturing in the 18th Century, 1973.

Located on Tulpehocken Creek in Berks County, Charming Forge exemplified two steps in American iron production in the 1700s and early 1800s. First, it was a refinery forge that processed iron from charcoal furnaces, which were primary iron producers, and like other refinery forges made wrought iron that blacksmiths and others could shape into various products. Second, Charming Forge had a slitting mill that turned wrought iron into slits that could be made into nails.

Michael Miller and John George Nikoll, a hammersmith who worked with iron, built Charming Forge about 1749 on Tulpehocken Creek and called it Tulpehocken Eisenhammer. In 1763

Refinery forges usually had two types of charcoal-heated hearths: a finery or refinery hearth and a chafery hearth. Workers heated rough bars of pig iron in a finery hearth until the iron became semi-molten. A skilled worker known as a finer then worked the semi-molten bars into a lump or half-bloom. Workers then used large hooks and wide-jawed tongs to place the glowing half-bloom on an anvil and pound it with a large water-powered forge hammer, a massive piece of iron mounted on an oak beam that connected to a water wheel.

Workers repeatedly reheated and pounded half-blooms until they produced flat, thick bars of wrought iron called anconies. The anconies not sold by the ironmasters were then reheated in a chafery hearth and hammered on an anvil to produce long bars of iron in different thicknesses. Forge workers then fashioned and cut the bars into shapes that blacksmiths and others could use. Workers also hammered out sheet and plate iron at some forges through the early 1800s.

The slitting mill at Charming Forge processed wrought iron bars from the refinery forge. Here, workers used heavy, water-powered shears to cut the bars into strips, then heated the strips and passed them through rollers that reduced the strips to a desired thickness. Next they reheated the strips and passed them through grooved rollers that cut the strips into slits.

Slit iron often went to naileries, which put points on one end of the iron slits and heads on the other end to produce nails. Ironmasters located earlier slitting mills in rural areas near refinery forges, their sources of wrought iron, but they placed later slitting mills nearer towns and cities, which were their principal markets.

In the early nineteenth century, Pennsylvania ironmasters like

By 1850 the iron industry had turned from forges to rolling mills, which produced wrought iron products and railroad rails cheaper, faster, and more efficiently. Charming Forge remained in operated until 1887, well after rolling mills has driven other refinery forges out of business.