![header=[Marker Text] body=[Buried in this cemetery is the famous minstrel, composer of "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" and many other songs. Born on Long Island in 1854, he traveled widely but died in obscurity at Philadelphia in 1911. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-26A-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h8b9-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

James A. Bland

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

Pa. 23 (Conshohocken State Rd.), Bala Cynwyd

Dedication Date:

September 26, 1961

Behind the Marker

In their representations of African Americans, both free and enslaved, minstrel troupes participated in the great cultural wars over the meaning of race that divided and fascinated Americans in the 1800s. And early on, Philadelphia became a center of this new form of show business. Before the Civil War, minstrel shows and songs reinforced negative racial stereotypes-and thus the American institution of race slavery. But they contained many other messages as well. After the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852, for example, "Tom shows," as they were called, offered sympathetic portrayals of African Americans.

An urban and northern form of entertainment, the minstrel show also spread the first of many waves of African-American inspired forms of popular music - including ragtime, jazz, the blues, rock and roll, and hip hop - that would achieve national and then international popularity. It also provided unprecedented opportunities for black songwriters and entertainers.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, newly-formed African-American minstrel troupes provided black entertainers with their best opportunity to break into American show business. Among them was James Bland, the greatest and most prolific African-American songwriter of the late 1800s. Born in Flushing, New York in 1854, Bland grew up in a family with rare educational advantages. His father, Allen Bland, a free black from South Carolina, had attended Oberlin, then graduated from Wilberforce before moving his young family to Philadelphia where James, according to legend, first heard an elderly black street musician and fell in love with banjo.

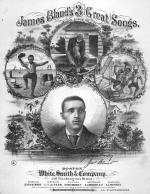

Soon after the end of the Civil War, the Blands moved to Washington D.C. where James' father earned a law degree at Howard University and became the first African American in the United States Patent Office. His parents had high aspirations for James, but since his early teens he had been performing in hotels around the city. Bland attended Howard University but dropped out to pursue a career as a performer. In 1878, he published his first minstrel song, "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny."

In 1880, Bland joined Haverly's Colored Minstrels, a popular and well-financed national touring company, and soon became a featured player, performing many of his own songs on banjo. In 1882, he accompanied the troupe to England, then remained there when it returned to the States. In the years that followed, Bland enjoyed enormous popularity. Celebrated as the "Idol of the Music Halls" in Great Britain, he toured the Continent to rave reviews - Germans ranked him with Stephen Foster and John Philip Sousa as America's great song writers - and enjoyed the high life of a wealthy entertainer. At the height of his fame, Bland was reported to be writing a new song every week, and earning an astronomical $100,000 a year.

Stephen Foster and John Philip Sousa as America's great song writers - and enjoyed the high life of a wealthy entertainer. At the height of his fame, Bland was reported to be writing a new song every week, and earning an astronomical $100,000 a year.

In 1890, at the height of his popularity, Bland returned to the States where he joined W.C. Cleveland's Colored Minstrel Carnival, and was reported to have purchased a 4 ¾ carat diamond - the largest ever worn by an African-American entertainer. But his career soon floundered, for Bland had lost touch with American musical tastes, and the old minstrel shows were losing their audiences to vaudeville, variety shows, and musical theater. While some leading African-American entertainers made the leap to vaudeville, Bland chose instead to go back to Europe, where his career continued to fade.

He left Europe for good in 1901, and finding no jobs in New York returned to Washington D.C. where he wrote an unsuccessful musical comedy. He then moved to Philadelphia for a job with one of the nation's last resident minstrel shows. Within a few years he was unemployed, broke, and in poor health. On May 5, 1911, James Bland died at the age of fifty-seven, obscure and unnoticed, of tuberculosis.

In the decades that followed, Bland was forgotten, and his songs often attributed to other writers, including Stephen Foster. During his lifetime Bland had written as many as 700 songs, but like Foster and other songwriters before the formation of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in the early 1900s, he received only a fraction of the money they produced. As was typical at that time, most of Bland's songs were published under the names of the white minstrel performers to whom he had sold them.

There his story may have ended, except for the enduring popularity of two of his compositions. Bland's star rose again in 1940 when the state of Virginia adopted "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" as its official state song. The politics of race and of the minstrel stage again reared their heads, when in 1946 Governor William Tuck of Virginia made the following comments at the dedication of a granite monument at Bland's recently rediscovered grave in Merion, Pennsylvania.

"The occasion serves to refute the malicious charge against our fair Commonwealth…" the Governor intoned, "that there is no mutuality of understanding, no tolerance, no cooperation, no love between members of the white and Negro races below the Mason and Dixon Line." Stating that Bland's association with Virginia blacks "so impressed him with the affection that these people held for their homeland that he was inspired to write this lovely nostalgic ballad," Tuck hoped that all would continue to sing the song and value the message it contains. Half a century later, Virginia Governor Douglas Wilder, himself the grandson of Virginia slaves, would lead the movement that led to the song's retirement as Virginia's official song in 1997.

Today, James Bland is recognized as one of America's great popular songwriters. He has been criticized for writing nostalgic "Negro songs" about happy Darkies on the plantation, urban dandies, and over-dressed religious celebrants. But his songs were never nasty or degrading. And his best remain among the nation's most beloved and enduring popular songs. Each New Year's Day, white working-class Philadelphians dress in lavish costumes and strut up Broad Street, singing their favorite songs. (Before the 1960s many did so in the traditional blackface of the minstrel stage.) The official theme song of the parade, "Oh Dem Golden Slippers," is a song that James Bland published in 1879.

"Carry me back to old Virginny,James Bland, 1878

There's where the cotton and the corn and 'tatoes grow,

There's where the birds warble sweet in the springtime,

There's where the old darkey's heart am long'd to go."

In their representations of African Americans, both free and enslaved, minstrel troupes participated in the great cultural wars over the meaning of race that divided and fascinated Americans in the 1800s. And early on, Philadelphia became a center of this new form of show business. Before the Civil War, minstrel shows and songs reinforced negative racial stereotypes-and thus the American institution of race slavery. But they contained many other messages as well. After the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852, for example, "Tom shows," as they were called, offered sympathetic portrayals of African Americans.

An urban and northern form of entertainment, the minstrel show also spread the first of many waves of African-American inspired forms of popular music - including ragtime, jazz, the blues, rock and roll, and hip hop - that would achieve national and then international popularity. It also provided unprecedented opportunities for black songwriters and entertainers.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, newly-formed African-American minstrel troupes provided black entertainers with their best opportunity to break into American show business. Among them was James Bland, the greatest and most prolific African-American songwriter of the late 1800s. Born in Flushing, New York in 1854, Bland grew up in a family with rare educational advantages. His father, Allen Bland, a free black from South Carolina, had attended Oberlin, then graduated from Wilberforce before moving his young family to Philadelphia where James, according to legend, first heard an elderly black street musician and fell in love with banjo.

Soon after the end of the Civil War, the Blands moved to Washington D.C. where James' father earned a law degree at Howard University and became the first African American in the United States Patent Office. His parents had high aspirations for James, but since his early teens he had been performing in hotels around the city. Bland attended Howard University but dropped out to pursue a career as a performer. In 1878, he published his first minstrel song, "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny."

In 1880, Bland joined Haverly's Colored Minstrels, a popular and well-financed national touring company, and soon became a featured player, performing many of his own songs on banjo. In 1882, he accompanied the troupe to England, then remained there when it returned to the States. In the years that followed, Bland enjoyed enormous popularity. Celebrated as the "Idol of the Music Halls" in Great Britain, he toured the Continent to rave reviews - Germans ranked him with

In 1890, at the height of his popularity, Bland returned to the States where he joined W.C. Cleveland's Colored Minstrel Carnival, and was reported to have purchased a 4 ¾ carat diamond - the largest ever worn by an African-American entertainer. But his career soon floundered, for Bland had lost touch with American musical tastes, and the old minstrel shows were losing their audiences to vaudeville, variety shows, and musical theater. While some leading African-American entertainers made the leap to vaudeville, Bland chose instead to go back to Europe, where his career continued to fade.

He left Europe for good in 1901, and finding no jobs in New York returned to Washington D.C. where he wrote an unsuccessful musical comedy. He then moved to Philadelphia for a job with one of the nation's last resident minstrel shows. Within a few years he was unemployed, broke, and in poor health. On May 5, 1911, James Bland died at the age of fifty-seven, obscure and unnoticed, of tuberculosis.

In the decades that followed, Bland was forgotten, and his songs often attributed to other writers, including Stephen Foster. During his lifetime Bland had written as many as 700 songs, but like Foster and other songwriters before the formation of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in the early 1900s, he received only a fraction of the money they produced. As was typical at that time, most of Bland's songs were published under the names of the white minstrel performers to whom he had sold them.

There his story may have ended, except for the enduring popularity of two of his compositions. Bland's star rose again in 1940 when the state of Virginia adopted "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" as its official state song. The politics of race and of the minstrel stage again reared their heads, when in 1946 Governor William Tuck of Virginia made the following comments at the dedication of a granite monument at Bland's recently rediscovered grave in Merion, Pennsylvania.

"The occasion serves to refute the malicious charge against our fair Commonwealth…" the Governor intoned, "that there is no mutuality of understanding, no tolerance, no cooperation, no love between members of the white and Negro races below the Mason and Dixon Line." Stating that Bland's association with Virginia blacks "so impressed him with the affection that these people held for their homeland that he was inspired to write this lovely nostalgic ballad," Tuck hoped that all would continue to sing the song and value the message it contains. Half a century later, Virginia Governor Douglas Wilder, himself the grandson of Virginia slaves, would lead the movement that led to the song's retirement as Virginia's official song in 1997.

Today, James Bland is recognized as one of America's great popular songwriters. He has been criticized for writing nostalgic "Negro songs" about happy Darkies on the plantation, urban dandies, and over-dressed religious celebrants. But his songs were never nasty or degrading. And his best remain among the nation's most beloved and enduring popular songs. Each New Year's Day, white working-class Philadelphians dress in lavish costumes and strut up Broad Street, singing their favorite songs. (Before the 1960s many did so in the traditional blackface of the minstrel stage.) The official theme song of the parade, "Oh Dem Golden Slippers," is a song that James Bland published in 1879.