![header=[Marker Text] body=[Plant here began in 1886. Acquired by Andrew Carnegie, 1890; by U.S. Steel, 1901. Workers here implemented advances in rolling mill and blast furnace processes before 1914; in pollution control, 1953. At peak of operations they manned six blast furnaces. Plant was in service until 1984.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-23B-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h6t7-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Duquesne Steel Works

Region:

Pittsburgh Region

County:

Allegheny

Marker Location:

East Grant Ave. and Linden St. (PA 837), Duquesne

Dedication Date:

October 12, 1997

Behind the Marker

"An infant in years, it is the acknowledged young giant and the mastodon of the unconquered and unconquerable Monongahela valley." So declared one local newspaper of the Duquesne Steel Works in a fit of overheated boosterism. Duquesne did, however, help propel  Andrew Carnegie into the front ranks of the steel industry. After building the Edgar Thomson works for making steel rails, Carnegie's acquisitions of

Andrew Carnegie into the front ranks of the steel industry. After building the Edgar Thomson works for making steel rails, Carnegie's acquisitions of  Homestead (1883) and Duquesne (1891) transformed his holdings into a true steel empire.

Homestead (1883) and Duquesne (1891) transformed his holdings into a true steel empire.

In the early twentieth century Duquesne formed a key part of U.S. Steel's production capacity and a showcase for its policy of "welfare capitalism," in which the corporation offered workers stock purchases, pension plans, and health benefits. In its use as the site for the final battle between the cyborg hero and his executioners in the movie Robocop (1987), Duquesne's steel works symbolized the ruined lives and economic plight of American rust belt cities.

The Duquesne mill had its origins as a state-of-the-art Bessemer steel rail mill, built on the Monongahela River across from McKeesport and the National Tube works. Its owners began production in 1889 with a new "direct" process for rolling rails. They soon added a twelve-furnace open hearth steel plant, each furnace pouring out fifty-ton heats of steel up to three times each day.

National Tube works. Its owners began production in 1889 with a new "direct" process for rolling rails. They soon added a twelve-furnace open hearth steel plant, each furnace pouring out fifty-ton heats of steel up to three times each day.

Carnegie coaxed the upstart into his fold by spreading rumors (in letters to railroad purchasing agents) that Duquesne's rails lacked "homogeneity." Hampered by this accusation, the owners could not make the works profitable and sold out to Carnegie within two years. Amazingly enough, once in the Carnegie fold, the mill's problems with "homogeneity" promptly vanished. Carnegie Company under Frick

Carnegie Company under Frick

In the next decade, Carnegie dramatically expanded the Duquesne plant. Adding a 200-acre riverfront property opened space for four massive new blast furnaces, which expressed Carnegie's cost-cutting obsession in material form. Automated loading equipment hoisted the charges of coke, iron ore, and limestone to the top opening of the furnaces, while at the bottom automated machines cast the flow of molten raw iron into solid ingots that dropped directly into waiting railroad cars. The new furnaces promptly smashed all records for iron production. Duquesne's twelve open-hearth steel furnaces fed a giant four-mill rolling complex that reduced ingots to a variety of semi finished bars and billets. A company railroad interconnected the principal Carnegie works to create a formidable steelmaking complex.

Rumors in 1900 that Duquesne would add finishing departments for its steel, and that Carnegie was planning a huge tube-making plant on Lake Erie, threatened a new round of vicious cutthroat competition. "If Carnegie begins to make tubes," thought industry insiders, "he may decide later to make axes, plows, machinery. He may wipe us all out with this new policy."

Banker J.P. Morgan already owned National Tube and a clutch of Chicago-area steel mills. In 1901 Morgan ended Carnegie's competitive threat. He combined Carnegie's Pittsburgh holdings along with his Chicago mills and some choice iron-ore properties in Minnesota to form U.S. Steel, the nation's first billion-dollar corporation. At Duquesne, U.S. Steel added even more iron and steelmaking capacity so that by 1918 it had fully six blast furnaces, thirty-three open-hearth furnaces, and twelve rolling mills.

The sprawling complex at Duquesne posed several problems for the rigidly antiunion U.S. Steel. The legion of workers - numbering 4,000 in 1910 and 6,000 by 1920 - confronted a fragmented and bewildering mill environment. An eight-block residential area separated the iron and steel making mills of the "upper" works from the rolling mills in the "lower" works. Skilled workers predominated in the rolling mills, but they were only 7 percent of blast furnace workers. Additional fragmentation resulted from the rising tide of immigrants, hailing from thirty different ethnic groups, filling the mill's semiskilled and unskilled ranks. Finally, with no effective plant- or company-wide hiring policies, individual foremen still ruled the roost. They hired and fired, many workers believed, too often with an eye toward favoritism of kin, ethnicity, or race. Worse, some foremen forced workers to pay kickbacks to keep their jobs.

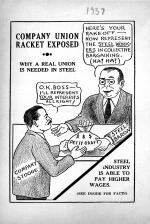

To respond to these labor problems, Duquesne beginning in 1904 became a showcase for U.S. Steel's well-publicized experiments with "welfare capitalism." American corporations adopted various "enlightened" labor measures in part to quiet the public's alarm about workers' long hours and dangerous working conditions.

Keeping unions out was often the overriding goal. The steel corporation's welfare capitalism combined the "stick" of refusing to recognize unions with the "carrot" of employee stock ownership, pension plans, accident insurance, housing, and other benefits. The managers at Duquesne and other U.S. Steel mills gave these modest benefits to employees who demonstrated "proper interest" in the company - and took them away from men who joined unions or went on strike.

In Duquesne, the company's welfare efforts centered on the town's Carnegie Library. In addition to housing books, chosen by the mill manager, the library building also contained a gymnasium, swimming pool, bowling alley, auditorium, and meeting rooms, also allocated by mill managers. Duquesne's mill managers had reasonable success, rare among U.S. Steel's plants, in expanding the welfare activities beyond skilled white workers. Semiskilled and unskilled workers, including many immigrants, also took up the company's carrots.

On balance, welfare capitalism had contradictory impacts. The company reaped a harvest of largely favorable publicity. Some Duquesne workers transferred their loyalties to the company, while others resented the company's manipulation. Diehard unionists either left town or laid low. The great steel strike of 1919 largely passed the mill by, even though the strike lasted fourteen weeks elsewhere. Nevertheless, town officials still harassed and bullied union organizers (Mother Jones was jailed for holding a union meeting), suggesting that not all workers were loyal and contented. Through the early 1930s the town government closed ranks with the mill and barred union organizers from holding any meetings. Workers understood that "if you'd even so much as mentioned the word 'union' around the plant, you got fired."

steel strike of 1919 largely passed the mill by, even though the strike lasted fourteen weeks elsewhere. Nevertheless, town officials still harassed and bullied union organizers (Mother Jones was jailed for holding a union meeting), suggesting that not all workers were loyal and contented. Through the early 1930s the town government closed ranks with the mill and barred union organizers from holding any meetings. Workers understood that "if you'd even so much as mentioned the word 'union' around the plant, you got fired."

African-American workers composed between 5 and 10 percent of Duquesne's workforce. They also received company welfare services such as classes, medical care, and sports teams, but they were forced to live in segregated boardinghouses and were barred from the library's pool, gymnasium, and meeting rooms. Work, too, was racially segregated. One African American in 1934 described the dead-end job prospects he faced: "I have never got any promotion. The highest paying job is cinder pit man in the open hearth, as far as colored are concerned. There is quite a few there. The next highest is furnace tender in the blast furnace department. In general colored have been kicking about the same level. The company just don't want them to go any higher."

Steel unionism arrived at Duquesne without dramatic strikes or lockouts. Duquesne's lower-skilled immigrant and African-American workers were especially active in the "rank and file" union movement in the early 1930s that sought to revive the Amalgamated Association, whereas skilled workers flocked to the "employee representation plan" that the company formed in 1933 as an extension of its welfare capitalism. Both these movements contributed leaders to the formal union structure that the Steel Workers Organizing Committee brought to U.S. Steel in 1937. The full victory of steel unionism at Duquesne occurred in May 1942, when workers voted overwhelmingly in favor of having SWOC as their sole bargaining agent with the company.

Steel Workers Organizing Committee brought to U.S. Steel in 1937. The full victory of steel unionism at Duquesne occurred in May 1942, when workers voted overwhelmingly in favor of having SWOC as their sole bargaining agent with the company.

Duquesne's fortune as a town was yoked to the prosperity of the mill. The town's population peaked in 1930 at 21,000. In 1948, the mill employed over 8,000 people, but as the mill lost jobs the population of the town slipped sharply, beginning in the 1960s. The town's magnificent Carnegie Library was razed in 1968.

The attempt to stop the tearing down of "Dorothy Six," the most modern and productive furnace in the Mon Valley, provoked mass rallies and an attempted buyout of the mill. The "Save Dorothy" campaign helped launch the Steel Valley Authority, a multi-municipality public authority dedicated to preserving jobs and blocking plant closings. Since closing down in May of 1984, the Duquesne mill might finally warrant the unsettling image of an extinct elephant.

Duquesne is certainly a postindustrial landscape, with fewer people living in the entire town (7,332) than there were mill workers in 1948. An eleven-acre site on the 250-acre property hosts the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank. And the nearby Nine Mile Run, the mill's dumping site for an unsightly ten-story mountain of blast-furnace slag, is now restored to green space. When it abruptly closed the mill U.S. Steel left behind decades of detailed labor records, an unusual find for historians, now deposited at the University of Pittsburgh.

To learn more about the impact of the Great Depression on Duquesne, click here.

click here.

In the early twentieth century Duquesne formed a key part of U.S. Steel's production capacity and a showcase for its policy of "welfare capitalism," in which the corporation offered workers stock purchases, pension plans, and health benefits. In its use as the site for the final battle between the cyborg hero and his executioners in the movie Robocop (1987), Duquesne's steel works symbolized the ruined lives and economic plight of American rust belt cities.

The Duquesne mill had its origins as a state-of-the-art Bessemer steel rail mill, built on the Monongahela River across from McKeesport and the

Carnegie coaxed the upstart into his fold by spreading rumors (in letters to railroad purchasing agents) that Duquesne's rails lacked "homogeneity." Hampered by this accusation, the owners could not make the works profitable and sold out to Carnegie within two years. Amazingly enough, once in the Carnegie fold, the mill's problems with "homogeneity" promptly vanished.

In the next decade, Carnegie dramatically expanded the Duquesne plant. Adding a 200-acre riverfront property opened space for four massive new blast furnaces, which expressed Carnegie's cost-cutting obsession in material form. Automated loading equipment hoisted the charges of coke, iron ore, and limestone to the top opening of the furnaces, while at the bottom automated machines cast the flow of molten raw iron into solid ingots that dropped directly into waiting railroad cars. The new furnaces promptly smashed all records for iron production. Duquesne's twelve open-hearth steel furnaces fed a giant four-mill rolling complex that reduced ingots to a variety of semi finished bars and billets. A company railroad interconnected the principal Carnegie works to create a formidable steelmaking complex.

Rumors in 1900 that Duquesne would add finishing departments for its steel, and that Carnegie was planning a huge tube-making plant on Lake Erie, threatened a new round of vicious cutthroat competition. "If Carnegie begins to make tubes," thought industry insiders, "he may decide later to make axes, plows, machinery. He may wipe us all out with this new policy."

Banker J.P. Morgan already owned National Tube and a clutch of Chicago-area steel mills. In 1901 Morgan ended Carnegie's competitive threat. He combined Carnegie's Pittsburgh holdings along with his Chicago mills and some choice iron-ore properties in Minnesota to form U.S. Steel, the nation's first billion-dollar corporation. At Duquesne, U.S. Steel added even more iron and steelmaking capacity so that by 1918 it had fully six blast furnaces, thirty-three open-hearth furnaces, and twelve rolling mills.

The sprawling complex at Duquesne posed several problems for the rigidly antiunion U.S. Steel. The legion of workers - numbering 4,000 in 1910 and 6,000 by 1920 - confronted a fragmented and bewildering mill environment. An eight-block residential area separated the iron and steel making mills of the "upper" works from the rolling mills in the "lower" works. Skilled workers predominated in the rolling mills, but they were only 7 percent of blast furnace workers. Additional fragmentation resulted from the rising tide of immigrants, hailing from thirty different ethnic groups, filling the mill's semiskilled and unskilled ranks. Finally, with no effective plant- or company-wide hiring policies, individual foremen still ruled the roost. They hired and fired, many workers believed, too often with an eye toward favoritism of kin, ethnicity, or race. Worse, some foremen forced workers to pay kickbacks to keep their jobs.

To respond to these labor problems, Duquesne beginning in 1904 became a showcase for U.S. Steel's well-publicized experiments with "welfare capitalism." American corporations adopted various "enlightened" labor measures in part to quiet the public's alarm about workers' long hours and dangerous working conditions.

Keeping unions out was often the overriding goal. The steel corporation's welfare capitalism combined the "stick" of refusing to recognize unions with the "carrot" of employee stock ownership, pension plans, accident insurance, housing, and other benefits. The managers at Duquesne and other U.S. Steel mills gave these modest benefits to employees who demonstrated "proper interest" in the company - and took them away from men who joined unions or went on strike.

In Duquesne, the company's welfare efforts centered on the town's Carnegie Library. In addition to housing books, chosen by the mill manager, the library building also contained a gymnasium, swimming pool, bowling alley, auditorium, and meeting rooms, also allocated by mill managers. Duquesne's mill managers had reasonable success, rare among U.S. Steel's plants, in expanding the welfare activities beyond skilled white workers. Semiskilled and unskilled workers, including many immigrants, also took up the company's carrots.

On balance, welfare capitalism had contradictory impacts. The company reaped a harvest of largely favorable publicity. Some Duquesne workers transferred their loyalties to the company, while others resented the company's manipulation. Diehard unionists either left town or laid low. The great

African-American workers composed between 5 and 10 percent of Duquesne's workforce. They also received company welfare services such as classes, medical care, and sports teams, but they were forced to live in segregated boardinghouses and were barred from the library's pool, gymnasium, and meeting rooms. Work, too, was racially segregated. One African American in 1934 described the dead-end job prospects he faced: "I have never got any promotion. The highest paying job is cinder pit man in the open hearth, as far as colored are concerned. There is quite a few there. The next highest is furnace tender in the blast furnace department. In general colored have been kicking about the same level. The company just don't want them to go any higher."

Steel unionism arrived at Duquesne without dramatic strikes or lockouts. Duquesne's lower-skilled immigrant and African-American workers were especially active in the "rank and file" union movement in the early 1930s that sought to revive the Amalgamated Association, whereas skilled workers flocked to the "employee representation plan" that the company formed in 1933 as an extension of its welfare capitalism. Both these movements contributed leaders to the formal union structure that the

Duquesne's fortune as a town was yoked to the prosperity of the mill. The town's population peaked in 1930 at 21,000. In 1948, the mill employed over 8,000 people, but as the mill lost jobs the population of the town slipped sharply, beginning in the 1960s. The town's magnificent Carnegie Library was razed in 1968.

The attempt to stop the tearing down of "Dorothy Six," the most modern and productive furnace in the Mon Valley, provoked mass rallies and an attempted buyout of the mill. The "Save Dorothy" campaign helped launch the Steel Valley Authority, a multi-municipality public authority dedicated to preserving jobs and blocking plant closings. Since closing down in May of 1984, the Duquesne mill might finally warrant the unsettling image of an extinct elephant.

Duquesne is certainly a postindustrial landscape, with fewer people living in the entire town (7,332) than there were mill workers in 1948. An eleven-acre site on the 250-acre property hosts the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank. And the nearby Nine Mile Run, the mill's dumping site for an unsightly ten-story mountain of blast-furnace slag, is now restored to green space. When it abruptly closed the mill U.S. Steel left behind decades of detailed labor records, an unusual find for historians, now deposited at the University of Pittsburgh.

To learn more about the impact of the Great Depression on Duquesne,